Blog Archives

Coaches: Stop Throwing Pitchers Into Games Cold

This is another one of those posts that you would think should generate a collective “duh” from the fastpitch softball world, but based on what I keep hearing it’s not quite as obvious as it would seem. So let me say this loudly for the people in the back:

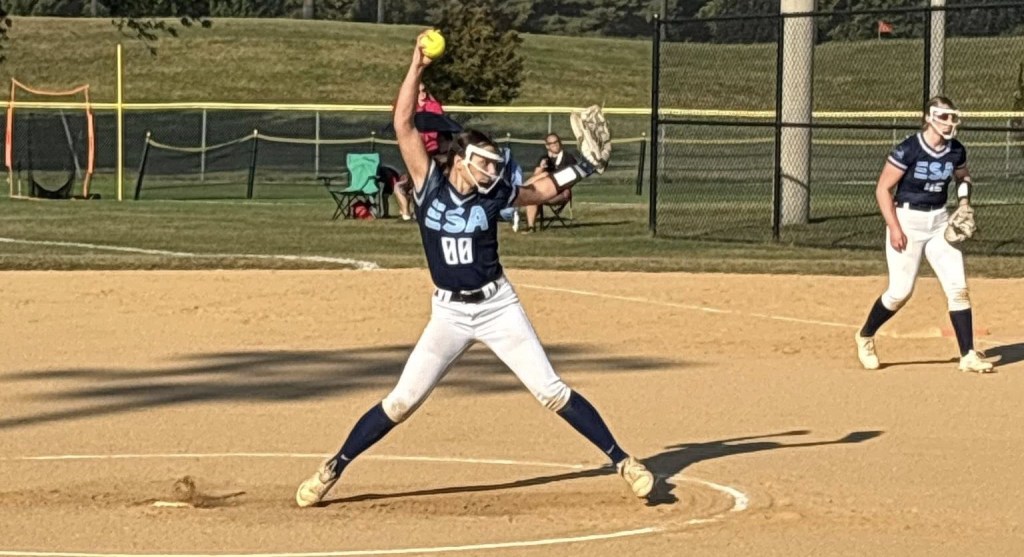

Coaches, you need to stop putting pitchers into games without adequate time to warm up before they take the circle.

That’s true even of pitchers who warmed up before the game started. If you’re now in the second, third, fourth, or later innings, those pitchers still need some time before they go in to get themselves ready.

And the longer it’s been since they initially warmed up, the more important it is to give them time to go through the process again. Because it takes a certain amount of preparation to get ready physically and mentally, to get the feel of various pitches, the complex timing required, and to switch their heads from field player (or sitting on the bench) to being game-ready.

Look, I know sometimes your pitchers make it look easy when they step into the circle at the beginning of the game. They’re bringing good velo, they have command of their pitches, they’re ripping through batting orders like tissue paper.

As a result, you may think that it’s a switch they can throw and instantly turn into SuperStud. Trust me, it’s not.

It takes time to get ready. And there’s a “use it or lose it” factor built into it.

A pitcher who warms up before the game starts to cool with each passing minute if she’s not pitching in the game. To all of a sudden pull her in from left field or first base or wherever she’s playing currently and expect her to perform at her peak is not only unrealistic. It’s self-sabotaging.

Think about the situation. You wouldn’t be suddenly pulling her in from another position (or the bench) if things were going well for the team.

You’re pulling her in because they’re not, and you’re hoping she can put out the fire. Only she’s really not ready to perform at her peak, so there’s a pretty good chance that instead of making things better she’ll either keep them the same or make them worse.

Sure, you might get lucky and get the out you need to end the inning. But that’s probably going to be the exception.

The more likely scenario is you’ll get a walk, or a hit by pitch, or she’ll give up a meatball that goes sailing to or over the fence as she’s trying to find her groove.

The consequences of that decision may not just affect that game either. You may shake that pitcher’s confidence, especially if you get angry that she didn’t save you from your own bad decision, causing her to be overly cautious the next time out so as not to let you and the team down again.

More importantly, putting a pitcher into a game without adequate warm-up and then expecting her to perform at her highest level is a recipe for an injury – possibly one that is season-ending. No one wants that.

You would never see a Major League Baseball manager or a P4 head softball coach put a pitcher into a game without warming him/her up thoroughly first. Why would you think a younger or even high school-aged player could do it?

Ok, now that we’ve established that concept, the natural follow-up question is “how much time does that additional warm-up require?” After, all, the pitcher did spend some time before the game getting ready, so it shouldn’t be too much, right? Right?

The reality is it depends entirely on the pitcher. Some can warm up quickly, and maybe just need a little tune up before going into the game. They can probably get by with 10 minutes or less.

Others have a lengthy process they must follow in order to feel ready. It could take them 20 minutes or more to go through all their pitches to make sure they’re working properly.

As the person making the decision of when to put them in, you need to be aware of what each pitcher requires and then try to plan ahead so they’re ready to go when you need them. Just don’t wait until you’re already in trouble before you get them up and throwing.

If you think there’s any chance you’ll need a pitcher out of the bullpen/off the bench, get them warming up after 2-3 innings, just to be safe. If you’ll need to pull in a pitcher who’s already playing in the field, send in a sub, even if it’s mid-inning.

Better to have her ready and not need her than need her and not have her ready.

Coming in to pitch mid-game is often tougher on pitchers than starting one. Especially if the wheels are already coming off the wagon.

Giving your relievers enough time to warm up according to their individual needs will save you all a lot of heartaches, as well as give you a better chance of winning more games. It will also help prevent the type of injuries that can ruin a season.

7 Lessons from the 2025 WCWS

Like many coaches I’m sure, over the last couple of weeks I’ve been telling my students that they should watch the Women’s College World Series games. See what they do and how they do it, because in most cases

it’s a master class in how to play the game.

Students aren’t the only ones who can learn from it, however. There were a lot of lessons in there for coaches at all levels as well.

In some cases it was the strategies those coaches followed, whether it was using the element of surprise (such as a flat-out steal of home) or how they used their lineups. In others it was how they dealt with their players through all the ups and downs of a high-stakes series, or even their body language (or practiced lack of it) when things went wrong.

So with the WCWS now concluded and a champion crowned, I thought it would be a good opportunity to recap and share some of those lessons (in no particular order). Feel free to add any you think I may have missed in the comments.

WARNING: There be spoilers here. If you have games stacked up to watch and are trying to avoid learning the outcomes of those games stop reading now, go fire up your DVR, then come back afterwards.

Individual Greatness Doesn’t Guarantee Success

Ok, quick, think about who were the biggest names going into this year’s WCWS. Odds are most of you thought of three pitchers in particular: Jordy Bahl, Karlyn Pickens, and NiJaree Canady.

They have been the big stories all season, and for good reason. All are spectacular players who make a huge difference for their teams.

Yet only one of those names – NiJaree Canady – was in the final series, and her team did not win the big prize. This is not a knock any of these women, because they are all outstanding.

It is merely an observation that for all their greatness, it wasn’t enough in this particular series. To me, the lesson here is not to get intimidated by facing a superstar and fall into the trap of thinking your team simply can’t match up.

Teagan Kavan, the Ace for Texas had almost double the ERA and WHIP versus NiJaree Canady, almost double the ERA of Karlyn Pickens (although their WHIPs were close), and a somewhat higher ERA and WHIP than Jordy Bahl. Yet in the end Kavan was the one holding the champion’s trophy.

Get out there and play your game as a team and you can overcome multiple hurdles as well.

Riding One Pitcher Doesn’t Work As Well As It Used To

Back in the days of Jennie Finch, Cat Osterman, Monica Abbott, Lisa Fernandez, etc., teams used to be able to ride the arm of one pitcher all the way to the championship. That is no longer the case.

One reason for that is the change in format, especially for the championship. It used to be you only had to win one final head-to-head matchup to take home the prize. Now, it’s best two out of three, which extends how much a pitcher in particular has to work, especially if you’re the team coming back through the loser’s bracket.

It’s not that today’s athletes are any less than those of the past either. I’d argue they’re probably better trained and better conditioned that even 10 years ago.

But the caliber of play has continued to increase, and every one of the players is now better trained and better conditioned than they used to be, with science and data leading the way. That elevation in performance makes it that much tougher to play at an athlete’s highest level throughout the long, grueling road to the final matchup.

The stress and fatigue of playing on the edge takes it toll, especially on the pitchers who are throwing 100+ pitches per game. And while the effort of pitching in fastpitch softball may not create the same stresses on the body as overhand pitching, repetitive, violent movements executed over and over in a compressed time period are going to take their toll.

Smart teams will be sure to develop a pitching staff and use that staff strategically to preserve their stars for as long as they can. Yes, when you get to the end you’re going to tend to lean on your Ace more.

But the more you can save her for when you need her at the end, the better off you will be.

(NOTE: This is not a critique of either coach in the championship series. This is more advice for youth and high school coaches who over-use their Aces to build their won-loss record instead of thinking ahead to what they will need for the end of the season.)

In a 3-Game Series, Winning Game 1 Is Critical

Winning that first game gives you some luxuries that can help you take the final game.

When you win game one, you have the ability to start someone other than your Ace because worst-case if you lose you still have one more game to try to win it all. You can bring your Ace back fresher, and you won’t have given opposing hitters as many looks at your Ace as they would have had otherwise.

If you lose game one, it’s do-or-die. You need to do what you need to do to keep the series going so you will pretty much be forced to use your Ace. She gets more tired, and opposing hitters get more looks at her in a short period of timing, helping them time her up or learn to see her pitches better.

That makes it rougher to win game three for sure.

Even the Best Players Make Errors Under Pressure

So there’s Texas, sitting on a 10-run lead in the top of the 5th inning with three outs, then two outs, then one out, then one strike to go. One more out and the run rule takes effect, making them the 2025 WCWS champions. I’m sure their pitcher, Teagan Kavan, was looking forward to it all being done since she’d throw her fair share of pitches in the WCWS too.

But then disaster struck. Texas Tech put the ball in play and a throwing error by Texas put what should have been the third out on base. Another throwing error and a couple of hits later the score is now 10-3 and Texas Tech feels revived.

I’m sure the original error was a play they’ve practiced a million times. But in that situation the throw pulled the first baseman off the bag and kept Texas Tech in the ballgame.

That’s something to remember with your own teams. Even the best players make mistakes and/or succumb to pressure. The key is to not hit the panic button (or the scream at players button) and instead keep your cool so the players calm down and get back to business.

Also notice Texas coach Mike White didn’t pull his shortstop in the middle of the inning because she made an error. Instead, he put his faith in her and she made plays later that preserved the win.

It Ain’t Over ‘Til It’s Over

Same situation but from the Texas Tech side. It would have been easy for them to say 10-0 was an insurmountable lead and begin to let up a little.

Instead, they battled to the final out, and played like they always believed they could still win it. While it would have been tough, if a few more things went their way who knows?

Every player on that side did their jobs to the best of their ability, always believing they could still take the lead. And for a while there it looked like they might.

Now, one thing they had was the luxury of time. With no time limits and no run limits, they had the potential to score enough runs to get back in the game.

It didn’t happen, but it could have. As long as you’re not restricted by time there’s always that chance you can come back. Keep doing your best and you never know what might happen.

Pay Attention to the Little Opportunities

You have to admit the steal of home by Texas Tech was both fun and a gutsy call. I don’t have any inside information on it, but I’m guessing Coach Gerry Glasco knew it was an opportunity long before he called for it. He just had to wait for the right situation.

In watching the replays, it looked to me like the catcher wasn’t paying attention when she threw the ball back, because who would be crazy enough to try to steal home like that? The Texas Tech runner, though, was on a flat-out sprint from the moment the pitch was released and she ended up scoring pretty much unchallenged.

The lesson her isn’t just to keep awareness of what’s happening when you’re on defense, although that’s important. It’s also to think ahead and see what’s happening on the field when you’re up to bat, to see if there are opportunities to advance baserunners or score without putting the ball in play.

It was a gutsy call for sure. But I doubt it was done without a lot of forethought.

Practice the Little Things Too

On the other side of the coin was the hit off the intentional walk in the first game of the championship series. After throwing the first three balls, NiJaree Canady apparently lost a bit of control on the last pitch and Texas took advantage of it, swinging on a pitch that was too close to the plate while the defense was relaxed knowing it was an intentional walk.

Again, I don’t have any inside information but I’ll bet Texas Tech didn’t spend much time practicing intentional walks. Why would they when they had the two-time NFCA Pitcher of the Year throwing for them? Why would she need to walk anyone intentionally?

So when the situation came up, perhaps she wasn’t quite as ready as she should have been. I know you may be thinking “how hard is it to throw a pitch to a spot off the plate for someone who has pinpoint control everywhere else?”

It’s actually harder than you think, and a skill that has to be practiced like any other. Your pitchers are used to throwing strikes. Throwing a ball on purpose may seem as foreign to them as throwing with the opposite hand.

If you think you might throw an intentional walk, or do anything else out of the ordinary for that matter, be sure you practice it first. The less you leave to chance the better chance you have of it working.

Murphy’s Law In Action

Cindy Bristow once told a clinic full of coaches “My girls make the same mistakes your girls do. They just make them faster.” Over the years I have found that to be true.

If things can go wrong they will go wrong. Nothing you can do will change that.

But you can be as prepared as possible, and remember that no one ever sets out to perform poorly. Those things just happen.

Even the best players and coaches make mistakes or have good intentions blow up in their faces. Hopefully we can all learn from them and use that knowledge to help us get better for the next time.

Changeups Work Better When You Call Them

Ask anyone who knows a thing or two about fastpitch softball pitching about the changeup and they’ll tell you it’s one of the greatest weapons a pitcher can have in her arsenal. The ability to take 10-15 mph off the speed of a pitch while making it look like it will be delivered at the pitcher’s top speed works at every level, from rec ball to college to international play.

Here’s the thing, though. Just like a $500 bat works better when you swing it than when you stand there watching pitches go by, the changeup is far more effective when you throw it.

Now, that may seem obvious but from what I hear from frustrated pitchers, parents, and pitching coaches across the country apparently it’s not. For whatever reason, it seems like when many or most coaches are calling games they prefer to try to blow the ball by the hitter with every pitch rather than mixing in changeups and offspeeds.

Even when the pitcher is clearly not capable of blowing the ball by every hitter on the opposing team.

Personally, I don’t get it. One of the fundamental tenets of pitching is that hitting is about timing and pitching is about upsetting timing.

What better way to upset timing than to throw a pitch that looks like it will be fast but actually comes out slow? Not only do you get to make the hitter look silly on that pitch, you’ve now planted the idea that she can’t just sit on the speed and hit it (because she doesn’t want to look silly again), which means you’re now living rent-free in her head.

I think in some cases one reason coaches will shy away from the changeup is they try one and the pitcher either throws it toward the sky or rolls it in. They’ll then make the decision it isn’t working so won’t call it again.

That’s crazy though. Does that mean if a pitcher throws a fastball in the dirt or into the backstop they won’t call the fastball anymore?

Of course not.

So why shy away from a great pitch when the first one doesn’t work? Try a few, and if it’s still not working then table it for that game and come back to it another time.

Now, I will admit that some fortunate coaches may have a pitcher who actually can blow the ball by all the hitters on opposing teams so they may feel that pitcher doesn’t need to throw a changeup in games. After all, she’s already successful without it.

But that’s short-term thinking. Because if the pitcher really is that good, and wants to continue playing at higher levels, she’s going to eventually find that speed alone no longer gets the job done.

And if she finds that out in college (as some do every year) she’s then going to be scrambling to try to learn to throw a pitch that she should have been throwing regularly since she first learned how to spot that fastball. It could make for a very rough season.

A good changeup has the opposite effect of a pitching machine. The reason most hitters find it tough to hit off a machine (at least at first) is that the speed of the arm feeding the ball doesn’t match the speed of the pitch coming out.

In other words, the arm moves slowly to put the ball in the feeder, but then the ball comes out at whatever high speed it’s set at. The visual cue of the arm doesn’t match the speed of the pitch and thus the hitter has trouble figuring out when to swing.

A great changeup gets the same effect in the opposite way. The visual cue of a well-thrown changeup makes it look like it will come at the pitcher’s top speed, but then the ball comes out 10-15 mph slower.

By the time the hitter’s brain has processed what’s happening she has either already swung or was frozen in place by the incongruity of what she saw, and doesn’t recover until after the umpire has called the pitch a strike.

None of that goodness can happen, however, unless someone actually calls for the changeup.

My recommendation on how to use the changeup is the same as the instructions for how to vote in Chicago: early and often.

Show it early so the hitters know it’s a possibility, meaning they shouldn’t get too comfortable. Even if it doesn’t work the first time it may just set the hitter up for the next speed pitch, i.e., it will make the fast pitch look faster.

Use it often to keep the hitters off-balance. Again, even if it’s not actually working the best.

Force the hitters to learn to have to lay off of it and maybe you’ll get a few more called strikes on other pitches as hitters and coaches try to guess when it’s coming. A little confusion at the plate goes a long way.

Finally, use it regularly to help your pitchers learn to throw it more reliably in games. Many coaches and programs talk about “developing players.”

Here’s a chance to put your money where your mouth is, metaphorically speaking. Help your pitchers become more effective in the long term by developing their changeups, even if it costs you a win now and then, and you’ll have fulfilled that part of your mission.

It’s easy to think of the changeup as being a “beginner pitch” because it’s usually the second pitch a pitcher learns. And because movement pitches such as drops, rises, curves, etc. seem more impressive.

But the reality is a pitcher who is changing speeds effectively, and at will, without tipping the pitch, is going to be awfully tough to hit at any level. Start calling the change more often and you just might be pleasantly surprised at the results it delivers for your pitcher – and your team.

Little Things That Make a Big Difference

It seems like softball coaches, players, and especially parents are always in search of the “silver bullet” – that one technique or piece of knowledge or magic adjustment that will take an average (or below-average) player and turn her into a superstar.

That desire is actually what keeps a lot of what I would call charlatans – people who claim to have a “secret sauce” when really what they have is a knack for hyping otherwise very ordinary solutions – in business. It’s also what drives some of the incredibly crazy drills or controversial posts you see on social media.

Well, that and a need to constantly feed things into the social media machine so they can keep getting those clicks.

In my experience there is no single silver bullet or secret sauce drill that can turn an average player into a superstar overnight. There is no “next big thing” either.

But there are a lot of little things that can make a huge difference in your game if you learn to execute them properly. Here’s a little collection of some of them.

Pitching a rise ball

The rise ball is often the toughest pitch to learn. That’s because getting true backspin on a 12 inch softball (versus the typical bullet spin) requires the pitcher to do some things that work against the body’s natural tendencies.

One of the biggest has to do with what the hand and forearm do at release.

The natural movement for the hand and forearm as they pass the back leg is to pronate, i.e., turn inward. If you hold your arm up and let it just drop behind you, you’ll see that inward turn when you get to the bottom of the circle.

Try it for yourself, right now. Go ahead, I’ll wait.

When you’re throwing a rise ball, however, you have to keep the hand and forearm in supination, i.e., pointed outward, as you go into release if you want to be able to cut under the ball and achieve backspin. Otherwise you’re throwing a drop ball.

What often happens, however, is that in trying to keep the forearm and hand pointed out, the pitcher will cup her hand under the ball so the palm is pointed toward the sky or ceiling. That may work to impart backspin when doing drills from a short distance away, but it will also create a “big dot” spin instead of a more efficient and active “small dot” spin when thrown full-out.

So, to throw a true backspin rise the pitcher needs to learn to keep the palm of her hand pointed mostly out to the side, with just a slight cupping of the fingers. In other words, throw with more of a fastball-type orientation (fingers down) going into release, then angle the hand back up slightly so the fingertips are under the ball instead of to the side.

Do that and you have a much better chance of getting 6 to 12 backspin. (For those unfamiliar with that term, think of an analog clock, with the spin direction moving from the bottom at 6:00 to the top at 12:00.)

Another key is to freeze the fingers at release rather than trying to twist the ball out like a doorknob.

Again, twisting or “twizzling” the ball (as Rick Pauly calls it) will work when you’re self-spinning or throwing at a short distance. But once you try to put any energy into the ball, your hand’s natural tendency to pronate or turn in (remember that from a few minutes ago?) will cause you to turn the palm forward and create bullet spin.

Now, if you can throw the ball 70 mph or more, I suppose it doesn’t matter how your rise ball is spinning so you can get away with that. But if you’re not, forget the twizzling and make sure your hand simply cuts under the ball like a 9 iron hitting a golf ball onto the green and you’ll have a lot more success with it.

Bend in slightly to the curve ball

The curve ball tends to have the opposite problem. Here, you want your hand to be palm-up (if you’re throwing a cut-under curve) so the spin axis is on top of the ball.

The problem is many pitchers will tend to extend their spines a little as they go to throw the curve, which will naturally make the hand tend to sag down, turning the palm more out and away rather than up.

To avoid that issue, try bending in slightly over your bellybutton (on the sagittal plan for those who love the technical terms). That slight bowing in makes it easier to maintain a palm-up orientation, placing the spin axis on the top of the ball and creating a better chance for the fast, tight spin that enables a late break.

Get hitting power from your hips, not your arms

Look, I get it. You hold your bat in your hands, which are at the ends of your arms. So logically you would think to hit the ball harder you should use your arms more if you want to swing the bat harder.

And yes, that will work if you’re on a tee, where the ball isn’t moving. But if you’re not 7 years old, it won’t work so well when the ball is moving.

The reason is when you use the arms to create power, you give up control of the bat. You’re just yanking it wildly and hoping something good would happen.

The better approach is to use your hips (and core) to generate energy through body rotation. More energy, in fact, than you can create with your arms.

Then use the arms to easily direct that energy toward the ball. Approaching it this way will give you the adjustability you need to take the bat to where the ball is going instead of where it was when you first started the swing.

Generating power from the hips first also gives you more time to see the ball before you have to commit the bat, further allowing you to fine-tune the path of the bat to where the ball will be when it gets close to the plate.

Remember, the difference between a great contact and a weak one, or no contact for that matter, can be measured in centimeters (fractions of an inch for those who don’t remember the metric system from school). The ability to make fine adjustments during the swing is often the difference between a great hit and a poor one. Or none at all.

Shoulder tilt creates bat angle

While we’re talking hitting, another small adjustment has to do with the angle of the shoulders at contact.

We’ve all heard the instruction to “swing level” at some point or another. Many of you may have even said it, or say it now.

But if by swing level you mean having the bat parallel to the ground you’re just asking for a season filled with pop-ups and ground balls.

If you look at great hitters at the point of contact, you’ll see that 99 times out of 100 they have an angle on the bat that slopes down from the handle to the barrel. If you look a little further, you’ll see that the angle of the bat usually matches the angle of the shoulders.

So…if you want to get a great bat angle to hit rising line drives and other powerful hits, you don’t really need to manipulate the bat. You just need to let the back shoulder tilt downwards toward the ball. This preferably happens about halfway through the turn rather than dropping the shoulder first and then turning.

Think of the back shoulder as an aiming device. Once you see where the ball is headed, take the back shoulder in that direction and swing on a plane that matches the shoulder angle.

Before you can say “Bob’s your uncle” (always wanted to use that one) you’re crushing the ball deep – without having to do any crazy manipulations.

A better way to put on your glove or mitt

Given the power of the Internet to spread information I’m surprised that this little trick isn’t more well-known.

When most people put on a softball glove or mitt, they tend to put it on as they do a regular glove, i.e., one finger in each slot. I mean, it makes sense, right?

But that’s now how the pros do it. The problem with the one finger, one slot approach is that you ring and little fingers are your two weakest fingers. Far weaker than the index and middle fingers.

So when you go to catch the ball, your weakest (little) finger is trying to close at least half, if not more, of the glove by itself while the strongest part of your hand is closing the other half. You don’t have to be an anatomy expert to figure out why that can contribute to a lot more dropped or mis-handled balls.

Here’s a trick that can solve that issue: Take your ring and little finger, hold them together, and then slide them into the loop in the last finger stall. Then move each of the other fingers over one toward that end, leaving the area for the first finger open.

Now your two weakest fingers have combined to create one stronger finger, better balancing the closing power between the thumb and other side of your hand. You middle finger also gives somewhat of an assist to the other two.

And bonus, you no longer have to leave your index finger out of the glove to keep it from hurting when the ball hits the palm of the glove because it’s not in that spot anymore!

It’s going to feel awkward at first, especially because your hand won’t go into the glove quite as deeply. But try it for a month. You’ll never go back to the old way.

Little things mean a lot

None of these little tips are earth-shaking or revolutionary. But each of them can make a significant difference in your performance.

If you’re struggling with any of these issues, give these tips a try. It’s amazing the difference a slight adjustment can make.

Developing Fastpitch Pitchers: The Speed v Accuracy Debate

One of the age-old questions when developing fastpitch pitchers is whether coaches should prioritize speed or accuracy.

Of course the real answer is they should focus on mechanics and everything else comes from that. In other words, focus on the process and the outcomes will take care of themselves.

Still, you do need some way of measuring whether the mechanics you’re working on are helping your pitcher get better or not. The two most common are speed and accuracy.

So we again come to that question: which of those should be the priority? In my opinion, the priority for young pitchers should be speed. Here’s why.

Let’s say you choose to prioritize accuracy. Understandable, especially if you are a team coach.

You want pitchers who can get the ball over the plate and get hitters swinging. After all, you can’t defend a walk and all that, and no one likes a walkfest.

The problem is, if you sacrifice speed for accuracy your pitcher will develop a way of pitching that is totally focused on that outcome. That will get her by up until about the age of 12, especially if you’re not playing high-level ball.

But at some point she will need to gain some speed or she won’t be pitching anymore. While it may have been good enough to “just get the ball over the plate” when she was younger and the opponents didn’t hit very well, those hitters have been developing too.

And they can now crush those slow meatballs all the way toward South America.

So she’s going to have to gain some speed. The problem is, that’s going to throw off her whole way of pitching because she’s going to need to use her body differently than she’s been doing it, which means her accuracy will go down anyway. And now she’s neither fast nor accurate.

Let’s look at it from the other side. If you focus on speed first, your pitcher may have some trouble throwing strikes at first.

Young people don’t always have total command of their bodies, and some have less than others. Which means you could have arms and legs (as well as pitches) going everywhere when they try to use their full energy But…

The more they work at it at full or near-full energy level, the better they’ll be able to feel their body moving in space. Pitches that were way wide, or going to the top of the backstop, or rolling in the dirt, start getting closer to being strikes.

The zone keeps narrowing until finally the pitcher can throw reliably. Only instead of throwing meatballs she’s bringing heat.

And as she gets older, the mechanics she developed to build that speed continue to be refined, giving her better and better control without having to go back to the drawing board and re-learn how to pitch.

In the end, it comes down to what your goals for that pitcher are. If all the team coach cares about is not giving up walks to ensure a better shot at wins in the short term, it might make sense to go for accuracy.

Your pitcher will definitely get more opportunity to pitch right now.

If, however, you’re looking to develop your pitcher in a way that delivers long-term success, put the priority on speed and let accuracy come later. Because by the time a pitcher is 13, she needs a minimum level of speed to even be considered for most teams, much less given the ball when it counts.

You show up to a tryout with speed and no one cares how many batters you walked or hit when you were younger. They may even be willing to take a chance on you if you look a little wild.

But show up throwing in the mid-40s or less and you’re probably not going to be pitching much no matter how accurate you are. Because by that time accuracy will be considered table stakes, not a point of differentiation.

The #1 Measure of the Quality of a Fastpitch Pitcher

Ask a group of fastpitch softball coaches or fanatics what the best way is to measure the quality of a pitcher and you’re going to get a variety of answers. Most of which come down to the three S’s – speed, spin, spot.

The most popular, in most cases, is likely to be speed. There’s no doubt about it that speed is important (it is called FASTpitch, after all). The higher the speed, especially at the younger or less experienced levels, the harder it will be (generally) for hitters to put a bat on the ball.

Speed is also easy to measure. You set up your radar gun, turn it on, and the highest number wins. Often you can also eyeball it, particularly if there is more than a couple of miles per hour difference between pitchers.

Others will tell you that speed is less important than spin. Being able to make the ball break – not just angle or bend toward a specific location but actually change direction as the pitch comes in – can really give hitters fits.

They think the ball will be in one location and orient their swings accordingly only to realize the ball is somewhere else by the time it reaches the bat. That phenomenon can either induce a poor hit or a swing and miss, depending on the pitch and the amount of break it has.

Finally, there will be those who insist that pitchers hitting their spots, i.e., throwing the ball to the location that is called within a couple of inches of that location, is really the be-all and end-all measure of a fastpitch pitcher. These are usually coaches who 1) believe in the infallibility of their pitch calling and/or 2) are looking for a reason not to pitch a particular pitcher who is otherwise doing just fine.

In my opinion, though, none of those three S’s are the most important measure of the quality of a pitcher. So what is?

It’s simple: the ability to get hitters out. Preferably with as few pitches as possible each inning.

Think about it. What does it take for your team to come off defense and get the opportunity to put runs on the board so you can win?

You need to get three outs, hopefully in a row but definitely at some point.

You’re not awarded any outs for your pitcher hitting a particular speed with her pitches, or getting a certain number of revolutions per minute/second on her breaking pitches, or nailing her locations 8 out of 10 times. The only thing you’re given an out for is the hitter either swinging and missing up to three times or hitting the ball in a way that your fielders can get her out.

(I was going to say easily out, but while that is preferred even a difficult out is an out. But it sure is safer when they’re easier.)

To me, a perfect inning for a pitcher is when she induces three shallow pop-ups to the first baseman. Easy to field, and if the first baseman fails to catch the ball in spite of that she can still pick up the ball and step on first rather than having to make a throw.

Not to mention a pitcher who can get hitters out with just a few pitches is going to keep her pitch count low, enabling her to throw more pitches throughout the weekend.

After all, the minimum for striking out the side is nine pitches. If your pitcher can get the side out in seven or eight pitches, that difference is going to add up over time. Particularly because even the best strikeout pitchers rarely require only nine pitches inning after inning.

Outs are the currency of our game. You only get so many – 21 in a non-timed game, maybe 12 or 15 in a typical timed game – so a pitcher who can make them happen efficiently is going to be more valuable at game time than one who merely looks good on paper.

So how does a pitcher become that low-count, efficient pitcher? Really, it’s through a combination of the three S’s.

Sure, she needs some measure of speed with which to challenge hitters. But she doesn’t have to be overpowering.

One of the most effective pitchers I ever coached, a young lady whose pitch counts were typically in the 8 to 12 per inning range, never threw above 54 on my Pocket Radar. But man could she throw to a hitter’s weakness and make the ball move as well as change speeds while making every pitch look like it would be the same.

In other words, she could also spin and spot the ball. All three together were a deadly combination for her, even against quality hitters.

She wasn’t the flashiest pitcher you’ve ever seen, and she probably wouldn’t be the one most coaches would choose first if they were watching several pitchers throw in a line. But when the game or the championship was on the line, she was usually the one her team wanted in the circle.

Because she knew how to get hitters out, plain and simple.

There’s no doubt that overpowering speed is impressive, and it can often make up for deficiencies in other areas. Just ask all those bullet spin “riseball” pitchers.

But if you want to win more games, don’t make speed, or spin, or spot alone your only deciding factor.

Look for the pitcher who knows how to get hitters out, doesn’t matter how. She’ll make you look like a smarter coach.

Champions Take Their Warm-ups Seriously

You see it before a game or practice everywhere there’s a ballfield.

Teams positioned in two opposing lines, randomly throwing balls in the general direction of the other line. And then chasing said balls behind them.

Hitters casually knocking balls off tees into the bottom of nets – or over the top. Pitchers sleepwalking through a reps of a K drill or slowly strolling through a walk-through instead of going full speed.

Not just youngling rec teams either. The same behavior can be seen with high school teams, travel ball teams, even college teams.

It’s players sleepwalking through warmups as if they are something to be (barely) tolerated before the “real thing” begins.

That’s unfortunate on many levels, but mostly for what it says about those players’ dedication and desire to play like champions.

You see, champions realize that we are a product of our habits. They also realize the importance of paying attention to details.

Warm-up drills should be about more than just getting your body moving and your muscles loose. They should also be preparing you to play or practice at your highest level.

So if you’re just going through the motions, waiting for practice or the game to start, you’re missing a real opportunity to get better.

Take that hitter who is basically just knocking balls off the tee before a game. Hopefully she knows what she needs to do to hit to her full potential, and what she needs to work on to get there.

So if she’s just taking any old swing to satisfy the requirement of working at that station she could actually be making herself worse instead of better because she’s building habits (such as arm swinging, dropping her hands, or pulling her front side out) that may let her get the ball off the tee but won’t translate into powerful hits in the game.

Or take the pitcher who is sleepwalking through her K drills instead of using that time to focus on whether her arm slot is correct, she is leading her elbow through the back half of the circle, and she is allowing her forearm to whip and pronate into release. She shouldn’t be surprised if her speed is down, her accuracy is off, and her movement pitches aren’t behaving as they should when she goes into a full pitch.

Even the throwing drills that often come right after stretching require more than a half-hearted effort. Consider this: as we have discussed before, 80% of all errors are throwing errors.

Which means if your team can throw better, you can eliminate the source of 8 out of 10 errors. Cutting your errors down from 10 to 2 ought to help you win a few more ballgames, wouldn’t you think? That’s just math.

Yet how many times have you seen initial throwing warmups look more like two firing squads with the worst aim ever lined up opposite of each other?

That would be a great time to be working on throwing mechanics instead of just sharing gossip. Not that there’s anything wrong with talking while you throw. But you have to be able to keep yourself focused on your movements while you chat.

Even stretching needs to be taken seriously if it’s going to help players get ready to play and avoid injury. How many times have you seen players who are supposed to be stretching their hamstrings by kicking their legs straight out and up as high as they can go take three or four steps, raise their legs about hip-high, take another three or four steps, then do the same with the other leg.

Every step should result in a leg raise, not every fourth step. And if young softball players can’t raise their feet any higher than their hips they have some major work to do on their overall conditioning.

Because that’s just pathetic. Maybe less screen time and more time spent moving their bodies would give them more flexibility than a typical 50 year old.

The bottom line is many players seem to think warm-ups are something you do BEFORE you practice or play. But that’s wrong.

Warm-ups are actually a very important part of preparing players to play at the highest level and should be treated as such. If you don’t believe it, just watch any champion warm up.

Don’t Just Put In the Time – Put In the Effort

One of the most common questions coaches get at the end of a lesson or practice session is, “How long and how often should my daughter practice?”

While it’s a legitimate concern – parents want to their daughters get the full benefit and they get a better return on their investment – I tend to think they’re asking the wrong question. Here’s the reason: practicing is not actual time-based; it’s quality-based.

Take two players who are at the same skill level and have been assigned the same drill(s) as “homework:”

- One diligently does the homework, being mindful of her movements and attempting to execute the skill the way she has been taught. She does this for 20 minutes three times before she has her next lesson.

- The other goes out to practice for a half hour three days a week between lessons. But she doesn’t like doing drills because it’s “boring,” so she instead just decides to pitch from full distance or take full swings or field ground balls hit by a partner etc. the whole time.

Which one do you think will show improvement in the aspect that needs the most help as well as in the overall skill?

Player two put in more time – an extra half hour to be exact. If time were the only factor that counted she should do better at the next lesson.

But I will tell you from experience, and bet you dollars to donuts, that player two will be the one who is most likely ready to advance further at the next lesson. She may not have put in as much time, but she put in more effort to solve her biggest issues – the one that is most limiting her.

So if she’s a pitcher who was straightening out her arm on the back side of the circle, she is now far more likely to have a nice elbow bend or “hook” as her arm gets ready to throw the ball. If she is a hitter who was dropping her hands straight to her waist before swinging, she’s far more likely to be keeping them up and turning the bat over to get the ball.

That’s because she mindfully worked at changing what she was doing. She is serious about improving so she put in the effort to make those changes.

Player two, on the other hand, actually put herself further away from her goals by practicing as she did, because all she did was reinforce the poor mechanics she should be trying to move away from.

Yes, she put in the time and could mark it down on a practice sheet, but she didn’t put in the effort. Without the effort to improve, the time is pretty much meaningless.

She would have ended up in exactly the same place at best if she hadn’t practiced at all. And she may have ended up further behind because now those extra reps with the wrong techniques will make it that much more difficult to get her to the right path.

If your daughter is going to spend her valuable time on practicing her softball skills, or anything else for that matter, make sure it’s on something that will help her advance her abilities forward.

Have her make the effort to concentrate specifically on the areas that need improvement rather than spending all her time making full pitches, full swings, etc. and you’ll see faster progress that leads to greater softball success.

P.S. For any parents of my students who may think I’m talking about their daughter, don’t worry. I’m not. It’s a big club. But do keep it in mind as you work with your daughter anyway!

To Improve Pitching Mechanics Try Closing Your Eyes

One of the most important contributors to being successful in fastpitch softball pitching (and many other skills for that matter) is the ability to feel what your body is doing while it’s doing it.

The fancy word for that is “proprioception” – your ability to feel your body and the movement of your limbs in space. If you want to impress someone call it that. Otherwise you can just say body awareness.

Yet while it’s easy to say you should have body awareness, achieving it can be difficult for many pitchers, especially (but not limited to) younger ones. Keep in mind that it wasn’t all that long ago they were learning to walk, and many are still struggling to improve their fine motor skills.

Perhaps one of the biggest obstacles to achieving body awareness, however, is our eyes. How often do we tell pitchers to focus on the target, or yell at catchers to “give her a bigger target” when a pitcher is struggling.

According to research, 90% of what our brains process is visual information. That leaves very little processing power for our other senses.

It makes sense from a survival point of view. We can see threats long before we can hear them, or smell them, or taste them.

But if your goal is oriented toward athletic performance instead of survival, all that visual information can get in the way of feeling what your body is doing.

The solution is as simple as it is obvious: if you can’t feel your body when you’re practicing, close your eyes. (I do not recommend the same during a game since there is a person with a $500 bat at the other end of the pitch waiting to drill you with a comebacker.)

With your eyes closed, you no longer have the distraction(s) of what your eyes see. You HAVE to become more aware of what your body is doing, and where its various parts are going, if you’re going to have any chance of getting it even near the plate.

I have done this with many pitchers over the years, and it has invariably helped to different degrees. Some start to feel whether their arms are stiffening up or they’re pushing the ball through release where they couldn’t before.

Some feel their bodies going off line, or gyrating in all kinds of crazy directions instead of just moving forward and stabilizing at release.

In some cases, girls who were struggling with control actually start throwing more strikes with their eyes closed than they did with their eyes open. Again, because they’re starting to FEEL the things we were talking about.

One thing I like to emphasize with eyes-closed pitching is for the pitcher to visualize where the catcher is before she starts the pitch. See it in her mind’s eye the way she would see it if her eyes were open.

Then, once she has it visualized, go ahead and throw the pitch.

Even if she struggles at first she will usually start to feel what her body is doing at a much deeper level, putting her in a position to start correcting it. Then, by the time she opens her eyes again she will be better prepared to deliver the type of results you’re hoping for.

If you have a pitcher who is struggling to feel what she’s doing, give this a try. It can be an eye-opening experience for pitchers – and their parents.

IR Won’t Put Young Pitchers in the ER

Let me start by declaring right in the beginning I am a huge advocate of the pitching mechanics known as “internal rotation” or IR. While it may also go by other names – “forearm fire” and “the whip” comes to mind – it essentially involves what happens on the back side of the circle.

With IR, the palm of the hand points toward the catcher or somewhat toward the third base line as it passes overhead at 12:00 (aka the “show it” position), the comes down with the elbow and upper arm leading through the circle. From 12:00 to 9:00 it may point to the sky or out toward the third base line. Then something interesting happens.

The bone in the upper arm (the humorous) rotates inward so the underside of the upper comes into contact with the ribs while the elbow remains bent and the hand stays pointed away from the body until you get into release, where it quickly turns inward (pronates). It is this action that helps create the whip that results in the high speeds high-level pitchers achieve.

This action, by the way, is opposite of so-called “hello elbow” or HE mechanics where the ball is pointed toward second at the top of the circle and is then pushed down the back side of the circle until the pitcher consciously snaps her wrist and then pulls her elbow up until it points to the catcher.

Note that I don’t call these styles, by the way, because they’re not. A “style” is something a pitcher does that is individual to them but not a material part of the pitch, like how they wind up. What “style” you use doesn’t matter a whole lot.

But mechanics are everything in the pitch, and the mechanics you use will have a huge impact on your results as well as your health.

IR is demonstrably superior to HE for producing high levels of speed. The easiest proof is to look at the mechanics of those who pitch 70+ mph. You won’t find an HE thrower in the bunch, although you’ll probably find a couple who THINK they throw that way, which is a sad story for another day.

It also makes biomechanical sense that IR would produce better speed results. Imagine push a peanut across a table versus putting into a rubber band and shooting it across the table. I know which one I’d rather be on the receiving end of.

So when trying to defend what they teach, some HE pitching instructors will respond by questioning how safe it is to put young arms into the various positions required by IR versus the single position required by HE. They have no evidence, mind you. They’re just going by “what they’ve heard” or what they think.

Here’s the reality: IR is so effective because it works with the body is designed to work rather than against it. Try these little body position experiments and see what happens.

Experiment #1 – Jumping Jacks Hand Position

Anyone who has ever been to gym class knows how to do a jumping jack. You start with your hands together and feet at your side, then jump up and spread your feet while bringing your hands overhead. If you’re still unsure, Mickey Mouse will demonstrate:

Look at what Mickey’s hands are doing. They’re not turning away from each other at the top, and they’re definitely not getting into a position where they would push a ball down the back side of the circle. They are rotated externally, then rotating back internally.

Experiment #2 – How You Stand

Now let’s take movement out of it. Stand in front of a mirror with your hands at your sides, hanging down loosely. What do you see?

If you are like 99% of the population, your upper arms are likely touching your ribs and your hands are touching your thighs. In other words, you’re exactly in the delivery position used for IR.

To take this idea further, raise your arms up about shoulder high, then let them fall. At shoulder height your the palms of your hands will either be facing straight out or slightly up unless you purposely TRY to put them into a different position.

When they fall, if you let them fall naturally, they will return to the inward (pronated) position. And if you don’t stiffen up, your upper arms will lead the lower arms down rather than the whole arm coming down at once.

What this means is that IR is the most natural movement your arm(s) can make as they drop from overhead to your sides. If you’re using your arms the way they move naturally how can that movement be dangerous? Or even stressful?

When they fall, you will also notice that your upper arms fall naturally to your ribcage and your forearms lightly bump up against your hips, accelerating the inward pronation of your hands. This is what brush contact is.

Brush contact is not a thwacking of the elbow or forearm into your side. If you’re getting bruised you’re doing it wrong.

Think of what you mean by saying your brushed against someone versus you ran into them. Brushing against them implies you touched lightly and slightly altered your path. Bumping into them means you significantly altered your path, or even stopped.

The brush not only helps accelerate the inward turn. It also gives you a specific point your body can use to help you release the ball more consistently – which results in more accurate pitching. It’s a two-fer that helps you become a more successful pitcher.

Experiment #3 – Swing Your Glove Arm Around

If you use your pitching arm you may fall prey to habits if you’ve been taught HE. So try swinging your glove arm around fast and loose and see what it does.

I’ll bet it looks a lot like the IR movement described above. That’s what your throwing arm would be doing if it hadn’t been trained out of you.

And what it actually may be doing when you throw a pitch. You just don’t know it.

Reality check

The more you look at the biomechanics of the IR versus HE, the more you can see how IR uses the body’s natural motions while HE superimposes alternate movements on it. If anything, this means there’s more likelihood of HE hurting a young pitcher than IR.

The forced nature of HE is most likely to show up in the shoulder or back. Usually when pitchers have a complaint with pain in their trapezius muscle or down closer to their shoulder blades, it’s because they’re not getting much energy generated through the HE mechanics and so try to recruit the shoulders unnaturally to make up for it. That forced movement places a lot of stress on it.

They may also find that their elbows start to get sore if they are really committed to pulling the hand up and pointing the elbow after release, although in my experience that is more rare. Usually elbow issues result from overuse, which can happen no matter what type of mechanics you use.

The bottom line is that if the health and safety of young (or older for that matter) pitchers is important to you, don’t get fooled by “I’ve heard” or “Everybody knows” statements. Make a point of checking to see which way of pitching works to take advantage of the body’s natural movements, which will minimize the stress while maximizing the results.

I think you’ll find yourself saying goodbye to the hello elbow.