Category Archives: Health/safety

Champions Take Their Warm-ups Seriously

You see it before a game or practice everywhere there’s a ballfield.

Teams positioned in two opposing lines, randomly throwing balls in the general direction of the other line. And then chasing said balls behind them.

Hitters casually knocking balls off tees into the bottom of nets – or over the top. Pitchers sleepwalking through a reps of a K drill or slowly strolling through a walk-through instead of going full speed.

Not just youngling rec teams either. The same behavior can be seen with high school teams, travel ball teams, even college teams.

It’s players sleepwalking through warmups as if they are something to be (barely) tolerated before the “real thing” begins.

That’s unfortunate on many levels, but mostly for what it says about those players’ dedication and desire to play like champions.

You see, champions realize that we are a product of our habits. They also realize the importance of paying attention to details.

Warm-up drills should be about more than just getting your body moving and your muscles loose. They should also be preparing you to play or practice at your highest level.

So if you’re just going through the motions, waiting for practice or the game to start, you’re missing a real opportunity to get better.

Take that hitter who is basically just knocking balls off the tee before a game. Hopefully she knows what she needs to do to hit to her full potential, and what she needs to work on to get there.

So if she’s just taking any old swing to satisfy the requirement of working at that station she could actually be making herself worse instead of better because she’s building habits (such as arm swinging, dropping her hands, or pulling her front side out) that may let her get the ball off the tee but won’t translate into powerful hits in the game.

Or take the pitcher who is sleepwalking through her K drills instead of using that time to focus on whether her arm slot is correct, she is leading her elbow through the back half of the circle, and she is allowing her forearm to whip and pronate into release. She shouldn’t be surprised if her speed is down, her accuracy is off, and her movement pitches aren’t behaving as they should when she goes into a full pitch.

Even the throwing drills that often come right after stretching require more than a half-hearted effort. Consider this: as we have discussed before, 80% of all errors are throwing errors.

Which means if your team can throw better, you can eliminate the source of 8 out of 10 errors. Cutting your errors down from 10 to 2 ought to help you win a few more ballgames, wouldn’t you think? That’s just math.

Yet how many times have you seen initial throwing warmups look more like two firing squads with the worst aim ever lined up opposite of each other?

That would be a great time to be working on throwing mechanics instead of just sharing gossip. Not that there’s anything wrong with talking while you throw. But you have to be able to keep yourself focused on your movements while you chat.

Even stretching needs to be taken seriously if it’s going to help players get ready to play and avoid injury. How many times have you seen players who are supposed to be stretching their hamstrings by kicking their legs straight out and up as high as they can go take three or four steps, raise their legs about hip-high, take another three or four steps, then do the same with the other leg.

Every step should result in a leg raise, not every fourth step. And if young softball players can’t raise their feet any higher than their hips they have some major work to do on their overall conditioning.

Because that’s just pathetic. Maybe less screen time and more time spent moving their bodies would give them more flexibility than a typical 50 year old.

The bottom line is many players seem to think warm-ups are something you do BEFORE you practice or play. But that’s wrong.

Warm-ups are actually a very important part of preparing players to play at the highest level and should be treated as such. If you don’t believe it, just watch any champion warm up.

The Downside of Being a Multi-Sport Athlete

There are many benefits to being a multi-sport athlete, as has been detailed here as well as in numerous articles and athlete-driven promos across the Internet. The cross-training, the different styles of coaching, the different atmospheres, etc. all contribute to making a well-rounded athlete who can compete more effectively.

The old-school types in particular love to talk about all the great things that come with participating in multiple sports, and how they did it and it made them better all the way around.

But there’s a very definite downside in today’s world, especially if you want to compete at a high level. The downside is the time commitment required and its effect on the athlete’s physical and mental state.

You see, back in the “good old days” of multi-sport athletes each sport had a season. You played volleyball or ran cross country or did whatever in the fall. When that season was over it closed out and the athlete moved on to basketball or swimming or whatever in the winter. Then came softball or track or another sport, which was separated from everything else.

Today, however, every sport seems to be 24 x 7 x 365. A typical day will see an athlete attend a game for a school sport in one season as well as a practice for another sport that is out of season. Throw in lessons, speed and agility sessions, weightlifting classes – not to mention school/homework and possibly work for the older players – and it’s amazing these players can stand upright much less participate in so many activities.

In the summer they don’t have school to contend with, but often they have two or even three full-blown teams in different sports running at once along with the other activities. No rest for the wicked, eh?

What it often means is athletes who are never 100% healthy or energized. Instead, they are doing the best they can each day, but not necessarily the best they’re capable of.

What’s the solution? The ideal situation would be setting up a system where the governing bodies of various sports get together to set priorities.

Each sport would have a full-on season where they take the bulk of the time, while the others step back to a very limited level. For example, in the summer softball would have priority, and sports like basketball and volleyball would hold no tournaments on the weekends and perhaps be limited to a single practice each week. In fall a different sport would have priority and summer sports would be limited in the same way.

Of course, that’s never going to happen. The sports culture here in America is too tied to winning for any sport to take a back seat to others, even if it’s for the benefit of the athletes themselves.

The next best alternative is for parents to keep an eye on their athletes and set the priorities for them. Even if it makes them unhappy.

They and their athletes should figure out which sport is their priority and make that the focus of their efforts. They should then, in my opinion, treat any other sports as fill-ins.

Rather than playing club/travel for every sport, play it for one and then do the others for school or at a rec level.

Club/travel coaches can also help out by voluntarily limiting practices to once a week when out of season, with liberal policies if their players have to miss due to a conflict with the main sport.

This plan may not solve everything, but it’s a start.

The level of commitment required these days is just insane in my opinion. It’s time to change the culture.

We need to make it possible for athletes to receive the benefits of being multi-sport athletes without the detrimental effects. It will be better for them, better for their parents, and ultimately better for their teams too.

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio on Pexels.com

Helping Players Feel Good about Themselves More Critical Than Ever

In February of this year the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed the most recent results of its survey on the mental health of youths, along with a 10-year analysis of trends in that area. The news, in many cases, isn’t good – especially for teenage girls

The Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2011-2021 showed that 57% of teenage girls reported feeling a persistent sense of sadness or hopelessness in the last year. That’s an all-time high, and a full 21 percentage points increase over 10 years ago. Additionally, 41% of teenage girls reported experiencing poor mental health in the last 30 days, and nearly one-third (30%) considered suicide over the last year versus 19% in 2011.

These are disturbing figures to say the least, and they are definitely trending in the wrong direction. So what can fastpitch softball coaches do to help the situation? Here are a few suggestions.

Create a Positive, Welcoming Atmosphere

Most of your players probably won’t show that they are experiencing feelings of sadness or hopelessness at practice or at games, but that doesn’t mean those feelings aren’t there.

Many may see playing softball as the best part of their day. It can be a refuge from all the rest of the turmoil of social media, peer pressure, grade pressure, etc. they’re facing.

But if practices and games consist of a lot of yelling, screaming, brutal criticism, and punishment, softball can quickly become one more burden contributing to the downhill spiral.

Instead of taking a command and control approach try being more positive with your players. Try to catch them doing good instead of always commenting on what they’re doing wrong.

I’m not saying you have to turn practice into a birthday party without the cake. There is certainly a time for correction and a need to hold players accountable.

But don’t make it all negative. Look for the positives and help players feel good about themselves when they perform well – or even make an effort to do things they couldn’t before.

You never know when a kind word or a metaphorical pat on the back might be the thing that keeps one of your players from becoming another sad statistic.

Pay Attention to Warning Signs

It’s unlikely any of your players will come out and say they’re feeling unhappy or having difficulty. People with depression in particular get really good at covering it up – at least until the dam breaks.

One thing to look for is a change in the way they interact with their teammates. If they are suddenly quiet and withdrawn where they were once boisterous and interactive it could be a sign something is going on with them.

It may just be a problem with a teammate or two, but it could also be a sign of something deeper. Either way, you’ll want to know about it and address is sooner rather than later.

This also applies to how they interact with you. If a player used to speak with you on a regular basis but has now become withdrawn it could be a sign of something deeper going on in their lives.

You can also look for a change of eating habits. If you’re doing team meals, or even just handing out snacks to keep your players fueled through a long practice, take not if someone suddenly stops eating or just picks at their food.

Pay attention to how they manage their equipment. Now, some players are just slobs who throw everything in their bags haphazardly. That doesn’t mean they’re experiencing sadness. In fact, some of the happiest players I’ve ever known have earned the name “Pigpen.”

If, however, a player used to take better care of her equipment but is now letting it stay dirty or putting it away in a random manner, you may want to initiate a conversation to check in on her mental health.

You may also notice a sudden loss of focus, such as a player making mentals errors she didn’t used to make. If she is having difficulty coping with her life she may not be able concentrate her efforts on the task at hand. Instead of just yelling “focus!” you might want to check if there is something deeper going on.

Finally, pay attention to whether a player is suddenly reporting more injuries or illnesses than she did before. That could be the case, or it could be a sign of her not being able to muster the enthusiasm to participate and using injury/illness as an excuse.

If it seems to be becoming a habit you may want to sit her down and find out if there is something more going on.

Offer a Sympathetic Ear

Many teens who experience these feelings of sadness or hopelessness tend to feel like there is nowhere they can go to discuss them. They’re afraid of their peers finding out, and some may be uncomfortable talking to their parents about it.

Make sure your players know they can always come to you to talk about what’s going on in their lives. That doesn’t necessarily mean you should try to solve them, however.

In simple cases you can offer some friendly advice and encouragement. Often times teens simply have a desperate need to be heard or to get what they’re feeling out in the open.

But if you suspect something deeper is happening in their lives you’ll want to refer them to a qualified, Board-certified mental health professional. That person will be trained to help teens work through their feelings and recognize deeper issues that could have a profound effect on their physical and mental health in the future.

Just showing you care in a meaningful way, however, can be just the boost that player needs to take the next step to getting past her issues.

Not “Soft”

There is a temptation for some among us to blame these mental health issues on kids today being “soft” or “snowflakes.” “Back in my day,” they like to say, “we didn’t have these problems.”

Actually you did, but no one talked about it. They just suffered in misery, and some took their lives, because no one was recognizing the problem.

It’s also true that life today is very different than it was 10, 15, 25 or more years ago. The pace is faster, and the exposure to impossible standards is relentless.

In softball terms that can mean seeing pitchers your age (or younger) throwing harder than you in social media posts and feeling like you’re not good enough. Never mind that you’ve added a few mph over the last several months and are doing well in your games. You’re still be compared to everyone in the country.

Or it can mean seeing all these hitters blasting home runs while you’re hitting singles, or seeing a list of “Top 10 12 year olds” and not seeing your name on the list.

None of that existed in the so-called “good old days.” But it does now.

That’s why it’s important to be aware of what’s happening with your players and do whatever you can to give them a great experience. You may not just change a game outcome or two. You could change a life.

Photo by Randylle Deligero on Pexels.com

The Kids Aren’t Alright. They’re Exhausted.

You see it all the time. Kids are at practice/lesson, or in a game, or in a tournament, etc. and they’re just not performing to the level at which they’re capable.

“C’mon Erin (or Lily or Leticia)!” parents or coaches yell. “Put some effort in. Quit dogging it and get your rear in gear.”

But the reality is Erin (or Lily or Leticia) may actually be giving all she has and more. Because the problem isn’t effort or intention. It could be fatigue.

According to a 2020 survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics and reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a little more than 10% of kids between the ages of 12 and 17 reported being tired every day or almost every day. Now, 10% doesn’t sound like a lot, but I’ll bet if you added in kids who report being tired at least some days during the week the number would go much higher.

What’s causing all this fatigue? One thing could be the crazy level of commitment that pretty much every activity (including fastpitch softball) demands throughout the year – and particularly through the school year.

In a lot of area, maybe most, kids have to wake up at 6:00 or 6:30 to get ready for school. They’re then there to say, roughly, 3:30. Once school is over they may have a school sport practice or game, one of which will happen every day during the week and often on Saturdays as well.

Once they’re done with school sports they rush to a team practice, sometimes in the same sport and sometimes in another. For example, they play volleyball at school and then head to softball practice, or strength and conditioning.

Now, if the other practice is happening once a week it has a minor impact. But a lot of teams these days practice 3-4 times a week IN THE OFFSEASON!

So now maybe that kid is being expected to go all-out physically and mentally for 4, 5, maybe even 6 hours with barely time to eat a little something for dinner.

By now it’s 8:00, 8:30, 9:00 or even later and the child who gave his/her all on the field and/or in practice still has to do a couple of hours of homework. Maybe more if there is a big project due or all the teachers loaded him/her up.

Then it’s brush your teeth and off to bed by 11:00 pm so you’re ready to start the cycle all over again.

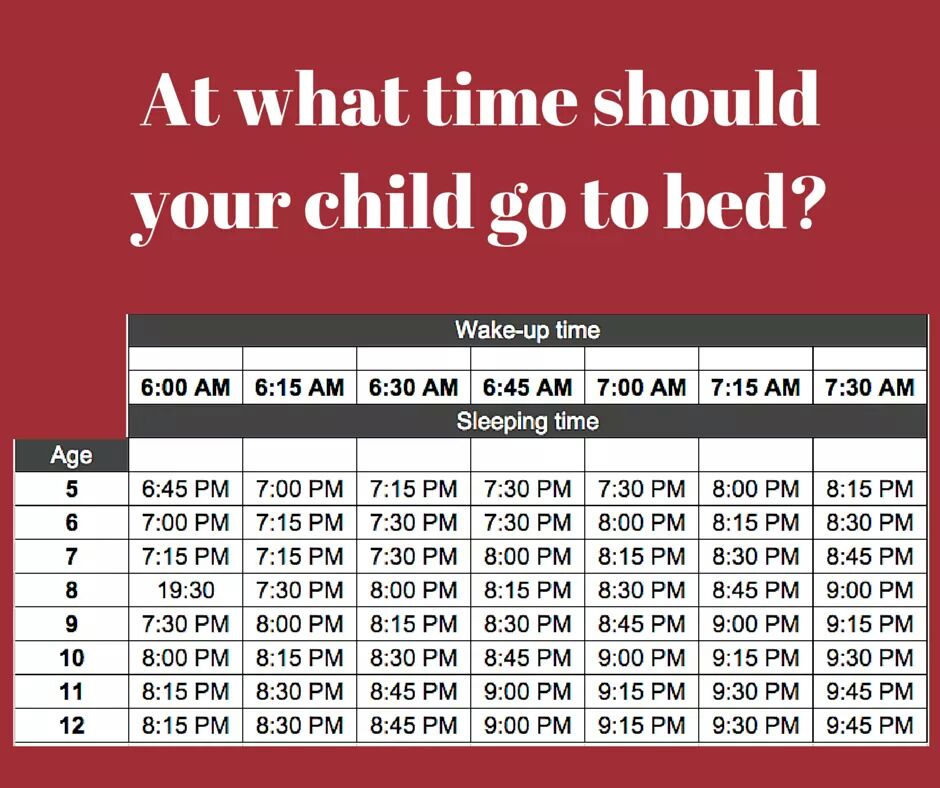

Here’s where the problem comes in. Take a look at the chart below, which shows what time kids should be going to be based on the times they wake up for school.

Notice a discrepancy here? That 12 year old who wakes up at 6:30 am should be in bed by 8:45 pm, not 11:00 pm. When it happens night after night the sleep bank gets drained.

Ok, but surely kids older than 12 can operate on less sleep? True, but not as much as you might think.

The CDC recommends that kids 13-18 should get a minimum of 8-10 hours of sleep per night. Every night.

I’ll save you the trouble of doing the math. To get 8 hours of sleep, that teen who wakes up at 6:30 am for school should be going to bed no later than 10:30. If he/she needs a little more sleep to function well, bedtime should get pushed earlier.

But it’s not just the sleep that is causing the problem. It’s also the lack of downtime.

Running from school to practice/game to practice/lesson/conditioning to whatever else is going on day after day after day takes a toll.

Pretty soon there’s very little left in the tank. Performance suffers and the risk of injury increases.

Ok, that’s the problem. What’s the solution?

I don’t have a final, definitive answer. But I do have a few suggestions.

Cut back on offseason practices – This applies to every sport, not just fastpitch softball. I firmly believe in the value of being a multi-sport athlete. But teams don’t need to maintain an in-season practice schedule during the offseason.

In reality, the fastpitch softball season is either February until the end of July(ish) or June until the end of October, depending on when your state plays school ball. During that time practice all you want.

Outside of it, there is no real reason to go more than once a week. If players want more, have them do it on their own, where they can focus their efforts for a half hour instead of enduring a two-to-three hour team practice.

That schedule includes the fall ball “season.” If you’re in a state that plays high school softball in the spring, fall ball is offseason so treat it that way.

If you just feel you must practice more than once a week, keep practices shorter, focusing on the single thing you want to accomplish.

Parents, make some hard choices – I get that many kids want to do everything. But there is a cumulative effect in trying to do all of that, especially if everything is at a high level.

A better solution might be for your child to play one sport at a high level (such as A-level travel softball) and other sports, if they want them, at more of a recreational level where the schedule demands aren’t so high.

There will always be exceptions, or course. Some kids are capable of playing more than one sport at a high level. Most are not, however, at least not without suffering some sort of consequences.

Parents need to take off the parent goggles and really look at how their kids are doing. If they’re always tired maybe it’s time to take some things off of their plates so they also have time to rest and recover.

Take sleep needs seriously – Although I shared them, I think the sleep guidelines above are tough to manage. They’re also kind of generic, because some kids will need less – and some will need more.

But going to bed late and getting only five or six hours of sleep on a regular basis isn’t good for anyone. Parents, be sure your kids are getting the opportunity to sleep, even if that means opting out of practice on a heavy homework night.

As an aside, teachers may want to re-think the homework loads they’re assigning as well. The recommendation from the National Parent-Teacher Association and the National Education Association is 10 minutes per grade level, i.e., 10 minutes for first grade, 20 for second grade.

That’s total, not per-class. In addition, research indicates that more than two hours of homework total may be counterproductive.

Teachers should work together to keep homework focused and productive. Parents should work with teachers when they see excessive amounts of homework being assigned to ensure there is awareness of this fact and that a solution is created.

The bottom line is many kids are tired – physically, mentally, emotionally. They are over-scheduled and their time is micromanaged to a ridiculous degree, often as a result of adults seeking validation through the performance of those kids.

It’s unlikely this situation is going to improve on its own. It’s time to recognize the symptoms before they start getting more out of hand and taking steps to reduce the strain.

In the process, you’ll probably find those kids are closer to providing the performance level you desire.

Photo by Matheus Bertelli on Pexels.com

It’s Getting to Be Time to Take a Break

Not for me – my work never ends. But for players we are coming to a natural point to dial back the softball activities so they can rest and recover and maybe experience other things life has to offer.

I know it can be difficult to think of stopping the relentless pursuit of perfection, whether that’s among coaches whose self-worth is tied up in their won-loss records or players (and by that I mostly mean parents) who are laser-focused on winning that college scholarship.

But everyone needs a little vacation from what they’re normally doing to ensure they continue to perform at their highest level the rest of the year.

Right now a lot of teams (although not all) have finished their seasons. Shockingly many have already held their tryouts and selected their teams for 2022-2023 so that’s out of the way.

Even those who haven’t quite finished are getting to the point of winding down the 2021-2022 season. So rather than jumping right into next year, why not put a pin in the softball activities for a little while and go do something else?

This advice, by the way, also applies to my own students. I love you all, but taking a little time off from lessons and practice so you can come at next season with a fresh perspective (and fresh body) would be a good thing. I’ll still be here when you’re ready to get going again.

Of course, for some of you who are all softball all the time you may not know what else to do with yourself. Here are 15 suggestions of how to spend the next few weeks.

- Lay around and do nothing. After the intensity of the season doing nothing in particular is perfectly acceptable.

- Sleep late. A lot of players skimp on the sleep during the season, especially high school and college players while school is in session. Take this time to build your sleep bank up again. You’re going to need it soon.

- Hang out at the pool or lake or water park (if it’s warm enough). Most coaches prohibit going to the pool on game or practice days because it can drain energy and hurt performance. Since every day is a game or practice day these days here’s your chance to enjoy the healing effects of floating in the water.

- Visit with non-softball friends. Sure, you love your teammates to death. But it’s ok to have non-softball or even non-athlete friends too. Go hang with them and do young people things.

- Visit family. Your grandparents would love to see you. So would your cousins. Spend some quality time with them. Because you may go from team to team but family is forever.

- Go to an amusement park. Spend the whole day there without thinking about what time you have to leave to make it to practice. Ride the roller coasters. See the shows. Eat junk (but not enough to throw up on the rides). In other words, have fun.

- Go to the zoo or a museum or a botanical garden. Anywhere you can take a leisurely stroll, look at things, and just BE.

- See a concert. Doesn’t have to be a big name star. It could just be a local band playing for free in the park, or at a local venue. Music is good for the soul. And since most performances occur at the same time as you normally practice or play, here’s your chance to hear music the way it was intended to be played – live!

- Watch a movie or a play in an actual theater. Just remember you’re not in your living room anymore so shut the heck up when the performance is happening.

- Go to dinner at a place where you don’t have to bring your own food to the table or where there aren’t 100 TVs playing sports all around you. Enjoy the experience of eating without worrying about what time to get back for warmups.

- Have a picnic. Yes, a good old-fashioned picnic where you bring some food and drinks, spread out a blanket, and just enjoy the day in the shade instead of on a blazing hot field.

- Go stargazing. Again, grab a blanket, go outside at night in a dark area, and just look up at the marvelous show above you. Appreciate how many stars there are, and remember that even if there is another planet out there somewhere with sentient beings they don’t care if you made an error, struck out, or hit a home run during the championship game this season.

- Have a campfire – or go camping. Building on #12, instead of going out for an hour get back to nature and either build a fire in the backyard (with parental supervision if required) or grab a tent and go to an actual campground and hang out in nature. There is something magical about staring at a real fire, especially outdoors (versus in a fireplace).

- Learn something entirely new that has nothing to do with softball. Play a musical instrument. Ask someone to teach you how to sew/knit/crochet. Take a course on computer programming. Try another sport like golf or tennis. Start collecting stamps or coins or something else that interests you. A good diversion will not only be good for now, but could also help you decompress once you get back to playing and practicing.

- Take a trip to somewhere new. It’s a big, wide world out there full of interesting people and places. Go somewhere where the goal is to experience the location instead of running from the hotel to the ballfield and back again.

These are just a few ideas. I’m sure you can come up with more if you give it some thought.

The key is to get away completely so you can rest, recover, put the last season behind you, and get ready to get back at it with even greater enthusiasm. Remember that absence makes the heart grow fonder.

Take a little time off of softball and you’ll probably find your love for it has grown even more while you’ve been away.

Photo by Mateusz Dach on Pexels.com

Light Bulb Moment: Athletic Efficiency

One of the concepts that can be tough for a young athlete (not to mention many adults) to understand is that stronger is not always better.

What I mean by that is that in their desire to throw harder, hit harder, run faster, etc. fastpitch softball players will often equate muscling up or tightening up with improved performance. They tend to take a brute force approach to their movements, assuming that if they work harder or produce more energy then they will ipso facto see better results.

Yet that isn’t always the case. In fact, sometimes the attempt at creating more energy through brute force works in the opposite manner by locking up joints or slowing down movements which reduces the amount of that energy that can be transferred into the activity.

In other words, despite the increase in energy the overall usage of energy becomes less efficient.

The reality is there are two key elements to maximizing athletic performance in ballistic movements such as pitching, throwing, hitting, and running.

First you have to create energy. Then you have to transfer that energy.

The brute force approach may work with part one. But it often gets in the way of part two, which means much of the energy the player worked so hard to create is wasted.

Makes sense, right? But how do you explain that to a player without making it sound like a science class lecture – at which point your voice starts to sound like Charlie Brown’s teacher?

The light bulb moment for me came when I was thinking about a light bulb I needed to replace during a lesson. Perhaps this will help you too.

Think about two types of light bulbs: the standard, traditional incandescent bulbs most of us grew up with (and that are now difficult to find) and LED bulbs.

If turn an old-school incandescent bulb on and leave it on for a few minutes, what happens to its surface? It gets hot. Very hot. As in don’t touch it or you will get burned.

That’s because while an incandescent bulb may be labeled 60 watts, not all of that wattage is going into creating light. In fact, much of it is being wasted in the form of heat.

Now think about an LED bulb. You can leave a 60 watt LED bulb on for an hour, then go over and put your hand on it without feeling much of anything. (DISCLAIMER: Don’t actually do that, just in case.)

The reason is that 60 watt LED bulb isn’t actually drawing 60 watts. That’s just a label the manufacturers use to help consumers know which bulb will give them the light level they’re used to.

In fact, that 60 watt equivalent bulb may be drawing as little as 8 actual watts to deliver the same amount of light as a 60 watt incandescent bulb. Since its purpose is to create light, not heat, the LED bulb is almost eight times as efficient as the incandescent bulb.

Now that’s apply that to softball. A pitcher who is nearly eight times as efficient in her mechanics as the next player will throw much harder with the same level of effort.

Conversely, she can perform at the same level as the other pitcher with almost no apparent effort at all. She is just much better at harnessing whatever level of energy she is creating and delivering it into the ball.

The same is true for hitters. Most of the time when you see a home run hit it doesn’t look like the hitter was trying to go yard. She just looks smooth as the ball “jumps” off her bat.

This is not to say strength isn’t important. It is.

Remember part one of the formula: you have to generate energy. Great training in mechanics along with intelligent sport-specific or even activity-specific training is critical to achieving higher levels of success.

But it’s not enough.

Understanding how the body moves naturally, and using those movements to take full advantage of the energy being created, will help players deliver higher levels of performance that enable them to achieve their goals and play to their greatest potential.

Hope this has been a light bulb moment for you. Have a great holiday, and take some time to relax. You’ve earned it.

Why Internal Rotation Produces Better Fastpitch Pitching Results

The other day I came across a great post on the Key Fundamentals blog titled Softball Pitching Myths Pt. 2 – Hello Elbow by Keeley Byrnes.

Keeley is a former pitcher and now a pitching coach in the Orlando, Florida area, and her blog has a lot of tremendous content on it. I highly recommend you check it out and bookmark or follow it as she has a lot of great information to share.

This particular post is a good example. It seems that “hello elbow” mechanics – turning the ball toward second at the top of the circle, pulling it down the back side and then forcing a palm-up finish at the end – is very commonly taught around the U.S. and maybe around the world.

Yet if you look at what elite pitchers do, you won’t find those mechanics being used by ANY of them. In fact, just the opposite, which makes it like learning to ride a bike by facing the back wheel instead of the front one.

Keeley’s well-researched post goes into great detail discussing not only what elite pitchers do by why they do it, and why it makes sense that they do it.

For example, she quotes this article from the U.S. National Library of Medicine which says:

“It has been shown that internal (medial) rotation around the long axis of the humerus is the largest contributor to projectile velocity. This rotation, which occurs in a few milliseconds and can exceed 9,000°/sec , is the fastest motion the human body produces.“

So if an internal rotation motion is the largest contributor to projectile (ball) velocity, why wouldn’t you want to use it? Seems like a no-brainer to me. Yet people still resist.

One of the interesting things about Keeley, along with Gina Furrey who I have mentioned in the past, is that both were taught “hello elbow” mechanics as players, and both now feel that not only did it limit their success, it also contributed to injuries that still plague them to this day.

When they first started out teaching they taught what they’d been taught. But then they did the research and discovered what they were teaching was actually sub-optimal, and they had the guts to change, which isn’t always easy.

Keeley goes as far as to show still photos of famous pitchers who appear to be pulling the hand up in a “hello elbow” manner, but then goes on to show what one of them actually does in a video. I’ve seen the others pitch and can tell you you’ll get similar results if you look at their full pitching motions.

Of course there is more to “hello elbow” than where the hand or elbow wind up. It’s actually a whole series of odd movements that rely on twisting the body, attempting to snap the wrist up at release and some other things that make it difficult to pitch efficiently – or effectively.

If that is what you, your daughter, or your team’s pitchers are being taught, I highly recommend checking out the Key Fundamentals blog where you’ll find a treasure trove of information that busts these myths, taken from the perspective of a former pitcher and practitioner. It’ll certainly open your eyes, and could save you a lifetime of regret.

IR Won’t Put Young Pitchers in the ER

Let me start by declaring right in the beginning I am a huge advocate of the pitching mechanics known as “internal rotation” or IR. While it may also go by other names – “forearm fire” and “the whip” comes to mind – it essentially involves what happens on the back side of the circle.

With IR, the palm of the hand points toward the catcher or somewhat toward the third base line as it passes overhead at 12:00 (aka the “show it” position), the comes down with the elbow and upper arm leading through the circle. From 12:00 to 9:00 it may point to the sky or out toward the third base line. Then something interesting happens.

The bone in the upper arm (the humorous) rotates inward so the underside of the upper comes into contact with the ribs while the elbow remains bent and the hand stays pointed away from the body until you get into release, where it quickly turns inward (pronates). It is this action that helps create the whip that results in the high speeds high-level pitchers achieve.

This action, by the way, is opposite of so-called “hello elbow” or HE mechanics where the ball is pointed toward second at the top of the circle and is then pushed down the back side of the circle until the pitcher consciously snaps her wrist and then pulls her elbow up until it points to the catcher.

Note that I don’t call these styles, by the way, because they’re not. A “style” is something a pitcher does that is individual to them but not a material part of the pitch, like how they wind up. What “style” you use doesn’t matter a whole lot.

But mechanics are everything in the pitch, and the mechanics you use will have a huge impact on your results as well as your health.

IR is demonstrably superior to HE for producing high levels of speed. The easiest proof is to look at the mechanics of those who pitch 70+ mph. You won’t find an HE thrower in the bunch, although you’ll probably find a couple who THINK they throw that way, which is a sad story for another day.

It also makes biomechanical sense that IR would produce better speed results. Imagine push a peanut across a table versus putting into a rubber band and shooting it across the table. I know which one I’d rather be on the receiving end of.

So when trying to defend what they teach, some HE pitching instructors will respond by questioning how safe it is to put young arms into the various positions required by IR versus the single position required by HE. They have no evidence, mind you. They’re just going by “what they’ve heard” or what they think.

Here’s the reality: IR is so effective because it works with the body is designed to work rather than against it. Try these little body position experiments and see what happens.

Experiment #1 – Jumping Jacks Hand Position

Anyone who has ever been to gym class knows how to do a jumping jack. You start with your hands together and feet at your side, then jump up and spread your feet while bringing your hands overhead. If you’re still unsure, Mickey Mouse will demonstrate:

Look at what Mickey’s hands are doing. They’re not turning away from each other at the top, and they’re definitely not getting into a position where they would push a ball down the back side of the circle. They are rotated externally, then rotating back internally.

Experiment #2 – How You Stand

Now let’s take movement out of it. Stand in front of a mirror with your hands at your sides, hanging down loosely. What do you see?

If you are like 99% of the population, your upper arms are likely touching your ribs and your hands are touching your thighs. In other words, you’re exactly in the delivery position used for IR.

To take this idea further, raise your arms up about shoulder high, then let them fall. At shoulder height your the palms of your hands will either be facing straight out or slightly up unless you purposely TRY to put them into a different position.

When they fall, if you let them fall naturally, they will return to the inward (pronated) position. And if you don’t stiffen up, your upper arms will lead the lower arms down rather than the whole arm coming down at once.

What this means is that IR is the most natural movement your arm(s) can make as they drop from overhead to your sides. If you’re using your arms the way they move naturally how can that movement be dangerous? Or even stressful?

When they fall, you will also notice that your upper arms fall naturally to your ribcage and your forearms lightly bump up against your hips, accelerating the inward pronation of your hands. This is what brush contact is.

Brush contact is not a thwacking of the elbow or forearm into your side. If you’re getting bruised you’re doing it wrong.

Think of what you mean by saying your brushed against someone versus you ran into them. Brushing against them implies you touched lightly and slightly altered your path. Bumping into them means you significantly altered your path, or even stopped.

The brush not only helps accelerate the inward turn. It also gives you a specific point your body can use to help you release the ball more consistently – which results in more accurate pitching. It’s a two-fer that helps you become a more successful pitcher.

Experiment #3 – Swing Your Glove Arm Around

If you use your pitching arm you may fall prey to habits if you’ve been taught HE. So try swinging your glove arm around fast and loose and see what it does.

I’ll bet it looks a lot like the IR movement described above. That’s what your throwing arm would be doing if it hadn’t been trained out of you.

And what it actually may be doing when you throw a pitch. You just don’t know it.

Reality check

The more you look at the biomechanics of the IR versus HE, the more you can see how IR uses the body’s natural motions while HE superimposes alternate movements on it. If anything, this means there’s more likelihood of HE hurting a young pitcher than IR.

The forced nature of HE is most likely to show up in the shoulder or back. Usually when pitchers have a complaint with pain in their trapezius muscle or down closer to their shoulder blades, it’s because they’re not getting much energy generated through the HE mechanics and so try to recruit the shoulders unnaturally to make up for it. That forced movement places a lot of stress on it.

They may also find that their elbows start to get sore if they are really committed to pulling the hand up and pointing the elbow after release, although in my experience that is more rare. Usually elbow issues result from overuse, which can happen no matter what type of mechanics you use.

The bottom line is that if the health and safety of young (or older for that matter) pitchers is important to you, don’t get fooled by “I’ve heard” or “Everybody knows” statements. Make a point of checking to see which way of pitching works to take advantage of the body’s natural movements, which will minimize the stress while maximizing the results.

I think you’ll find yourself saying goodbye to the hello elbow.

A Former Collegiate Pitcher Tells Her Overuse Injury Story

I have talked in the past about the dangers of the “it’s a natural motion” myth and how it can lead to overuse injuries. A quick search on the term will turn up article after article from orthopedic surgeons who have to deal with the aftermath of overzealous coaches who love to win and enthusiastic parents who just love watching their daughters do what they love.

How common are overuse injuries? While this study of 181 NCAA collegiate pitchers across all divisions is admittedly pretty old, it shows that 70% of the reported injuries were due to overuse. With the increase in the number of games that are now being played at the youth levels of travel ball, starting at 10U or even earlier, plus the even greater emphasis on winning, it’s unlikely this situation has gotten better.

But all of that is pretty abstract. That’s why I wanted to share this Tik Tok video from my friend and fellow pitching coach Gina Furrey, who talks about the overuse injuries she suffered as a pitcher. It is actually the first in a series, so be sure to watch all of them.

Gina currently gives pitching lessons in the Nashville, Tennessee area under the business name Furrey Fastpitch. If you’re in that area and looking for a great coach who will teach you proper mechanics be sure to contact her. You can also find Furrey Fastpitch on Facebook and on Instagram at @furreyfastpitch.

Before that, though, she was a player who played travel ball at the highest levels before going on to pitch at St. Mary-of-the-Woods college. In her first video she describes how she can probably count on one hand the number of games she didn’t pitch for her various teams throughout her career. That’s a LOT of pitching.

She then goes on to tell how her collegiate career was cut short by an injury attributed to overuse – the cumulative effect of thousands of hours practicing and pitching in games, often with very little rest. I don’t want to go into too many details because it’s Gina’s story to tell.

The biggest reason I think every coach and every parent of a pitcher should watch Gina’s videos, however, is to see her demonstrate her range of motion today. When you see what she can do with her non-pitching arm versus her pitching arm it’s pretty scary.

Not to mention the pain she deals with every day. In my opinion, all the plastic trophies and gaudy rings and plaques and championship t-shirts in the world are not worth trading for an ability to move your arm and shoulder in a normal way.

One caveat I’d like to add is that this caution isn’t only limited to pitchers with poor mechanics. Yes, having very clean pitching mechanics can help prevent injury overall, but over use is over use. Repetitive motions, especially high-energy motions that depend on sudden accelerations and decelerations, can take a huge toll on muscles, ligaments, tendons and other body parts.

Do yourself a favor. Please, please, please, watch Gina’s videos and hear her story. It could save you or someone you love a lifetime of pain and limitations that can easily be avoided.

Are We Destroying Our Kids?

Injuries have always been a part of participating in youth sports. Jammed fingers, sprained ankles and knees, cuts requiring stitches, even broken bones were an accepted part of the risk of playing. Things happen, after all.

Lately, though, we are seeing a continuing rise of a different type of injury. This one doesn’t happen suddenly as the result of a particular play or miscue on the field. Instead, it develops slowly, insidiously over time, but its effects can be more far-reaching than a sprain, cut or break.

I’m speaking, of course, about overuse injuries.

According to a 2014 position paper from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, roughly 46 to 54% of all youth sports injuries are from overuse. Think about that.

There was no collision. There was no tripping over a base or taking a line drive to the face. There was no stepping in a hole in the outfield or catching a cleat while sliding. The injury occurred while participating normally in the sport.

And here’s the scary part. As I said, this report came out in 2014. In the six years since, the pressure to play year-round, practice more, participate in speed and agility training and do all the other things that go with travel ball in particular has only gotten worse.

You can see it in how one season ends and another begins, as we recently went through. Tryouts keep getting earlier and earlier, with the result that players often commit to a new/different team before their finished playing with their current teams.

It’s not that they’re being bad or disloyal. It’s that they have no choice, because if they wait until the end of the current season there won’t be anywhere left to go because all the teams have been chosen.

What is even crazier is that there literally was no break for many players from one season to the next. I know of many for whom their current season ended on a weekend and their first practice for the next season was the week immediately after. Sometimes they were playing their first game with the new team before their parents had a chance to wash their uniforms from the old team.

And it wasn’t just one practice a week. Teams are doing two or three in the fall, with expectations that players will also take lessons and practice on their own as well.

That is crazy. What is so all-fired important about starting up again right away?

Why can’t players have at least a couple of weeks off to rest, recuperate physically and mentally, and just do other things that don’t require a bat, ball or glove? Why is it absolutely essential to begin playing tournaments or even friendlies immediately and through the end of August?

I think what’s often not taken into consideration, especially at the younger ages, is that many of these players’ bodies are going through some tremendous changes. Not just the puberty stuff but also just growth in general.

A growth spurt could mean a reduction in density in their bones, making them more susceptible to injuries. An imbalance in strength from one side to the other can stress muscles in a way that wouldn’t be so pronounced if they weren’t being used in the same way so often.

Every article you read about preventing overuse injuries stresses two core strategies:

- Incorporating significant periods of rest into the training/playing plan

- Playing multiple sports in order to develop the body more completely and avoid repetitive stress on the same muscles

When I read those recommendations, however, I can’t help but wonder: have the authors met any crazy softball coaches and parents?

As I mentioned, I’ve seen 12U team schedules where they are set to practice three times a week – in the fall! And these aren’t PGF A-level teams, they’re just local teams primarily playing local tournaments.

Taking up that much time makes it difficult to play other sports. Sure, the softball coach may say it’s ok to miss practices during the week to do a school sport, but is it really?

Will that player be looked down on if she’s not there working alongside her teammates each week? Probably.

Will that player fall behind her teammates in terms of skill, which ultimately hurts her chances of being on the field outside of pool play? Possibly.

So if softball is important to her, she’s just going to have to forego what the good doctors are saying and just focus on softball, thereby increasing her risk of an overuse injury.

This is not just a softball issue, by the way. It’s pretty much every youth sport. I think the neverending cycle may be more of a softball issue, but the time factor that prevents participation in more than one sport at a competitive level is fairly universal.

In the meantime, a study published in the journal Pediatrics that pulled from five previous studies showed that athletes 18 and under who specialize in one sport are twice as likely to sustain an overuse injury than those who played multiple sports.

The alarm bells are sounding. It’s like a lightning detector going off at a field but the teams deciding to ignore it and keep playing anyway. Sooner or later, someone is going to get struck.

What can you do about it? It will be tough, but we have to try to change the culture.

Leaders in the softball world – such as those in the various organizations (including the NFCA) and well-respected college coaches – need to start speaking up about the importance of reducing practice schedules for most of the year and building more downtime in – especially at the end of the season. I think that will help.

Ultimately, though, youth sports parents and coaches need to take responsibility for their children/players and take steps to put an end to the madness. Here are a few suggestions:

- Build in a few weeks between the end of the summer season and beginning of the fall season for rest, recovery and family activities. There’s no reason for anyone to play before Labor Day.

- Cut back on the number of fall and winter practices. Once a week with the team should be sufficient. Instead, encourage players to practice more on their own so they can fit softball activities around other sports and activities.

- Reduce the number of summer games/tournaments. Trying to squeeze 100+ games into three months in the summer (two for high school players who play for their schools in the spring season) is insane bordering on child abuse. Take a weekend or two off, and play fewer games during the week.

- Plan practices so you’re working on different skills in the same week. This is especially important when it comes to throwing, which is where a lot of overuse injuries occur. Work on offense one day and defense another. Or do throwing one day and baserunning another. Or maybe even play a game that helps with conditioning while working a different muscle group.

It won’t be easy, but we can do this. All it takes is a few brave souls to get it going.

Overuse injuries are running rampant through all sports, including fastpitch softball. With a little thought and care, however, we can reverse that trend – and keep our kids healthier, happier while making them better players in the process.