Austin Wasserman High Level Throwing Clinic in Chicago Area

Good news for my readers who live in the general north suburban area of Chicago – or are willing to get there from further away. The Pro Player Hurricanes are sponsoring a High Level Throwing clinic with Austin Wasserman November 14-15 in McHenry, Illinois. It’s at the Pro-Player Consultants facility, 5112 Prime Parkway, which is a great place for a clinic. I should know, because I teach lessons there.

There are two three-hour sessions each day that break down as follows:

Saturday, November 14

- Session 1: 10:00 am – 1 pm (10U-12U players)

- Session 2: 2:00 – 5:00 pm (13U-18U players

Sunday, November 15

- Session 1: 12:00 – 3:00 pm (10U-12U player)

- Session 2: 3:00 – 6:00 pm (13U-18U players)

The cost for a session is $150 per player. This is a rare opportunity to learn how to throw more powerfully – and safer – from one of the leading experts in the world.

Full information is available on the flyer (click the download button. If you want to up your daughter’s game with the overhand throw, be sure to get signed up by going to https://www.wassermanstrengthfl.com/high-level-throwing-clinic-mchenry-il/

Social Distancing Adds New Complications to Fastpitch Pitching

One of the keys to success in pitching in fastpitch softball or baseball is figuring out the umpire’s strike zone. While the rulebook offers certain parameters that should be universal (armpits to top of the knees, any part of the ball crosses any part of the plate, etc.) we all know even under the best of conditions it doesn’t always work out that way.

One of the keys to success in pitching in fastpitch softball or baseball is figuring out the umpire’s strike zone. While the rulebook offers certain parameters that should be universal (armpits to top of the knees, any part of the ball crosses any part of the plate, etc.) we all know even under the best of conditions it doesn’t always work out that way.

Many a pitcher (and a pitcher’s parent) has complained about umpires having a strike zone the size of a shoebox. And that shoebox is rarely in an area that contributes to pitchers keeping their ERAs low.

Instead, it’s far more likely to have the zero point on its X and Y axes about belt high, in the center of the plate. You know, that area that pitchers are taught they should see a red circle with a line through it.

Of course, these are anything but ordinary times. Here in the fall of 2020, in the midst of the worst pandemic in 100 years and with no relief in sight, teams, tournament directors and sanctioning bodies have had to take extraordinary steps to get games in. One of those is to place umpires behind the pitcher instead of behind the catcher in order to maintain social distancing.

It sounds good in theory, I’m sure. Many rec leagues using volunteer parents for umpires have had said Blues stand behind the pitcher. Sure beats spending money on gear.

But while it does allow games to be played, the practical realities have created a whole new issue when it comes to balls and strikes.

When the umpire is behind the plate, he/she is very close to that plate and thus has a pretty good view of where the ball crosses it. Not saying they always get it right, but they’re at least in a position to do so.

When they are behind the pitcher it’s an entirely different view. Especially in the older divisions where the pitchers throw harder and their balls presumably move more.

For one thing, the ball is moving away from the umpire instead of toward him/her. That alone offers a very different perception.

But the real key is that by the time the ball gets to the plate, exactly where it crosses on the plate and the hitter is much more difficult to determine. I don’t know this for a fact, but I’m sure the effects of parallax on vision has something to do with the perception.

Because it is more difficult to distinguish precisely, what many umpires end up doing is relying more on where the ball finishes in the catcher’s glove than where it actually crosses the plate. Not that they do it on purpose, but from that distance, at that speed, there just isn’t a whole lot of other frames of reference.

If an umpire isn’t sure, he/she will make a decision based on the most obvious facts at hand. And the most obvious is where the glove ends up.

This can be frustrating for pitchers – especially those who rely more on movement than raw power to get outs. They’re probably going to see their strikeouts go down and their ERAs go up as they are forced to ensure more of the ball crosses the plate so the catcher’s glove is close to the strike zone.

There’s not a whole lot we can do about it right now. As umpires gain more experience from that view I’m sure the best of them will make some adjustments and call more pitches that end up off the plate in the catcher’s glove. Most will likely open their strike zones a bit, especially if they realize what they’re seeing from in front of the plate isn’t the same thing they’d see from behind it.

Until that time, however, pitchers, coaches and parents will need to dial down their expectations in these situations. It’s simply a fact of life that hopefully will go away sooner rather than later.

In the meantime, my top suggestion is for coaches to work with their catchers to ensure their framing, especially side-to-side, is top-notch. Catching the outside of the ball and turning it in with a wrist turn instead of an arm pull may help bring a bit more balance to the balls-and-strikes count.

Pitchers will have to work on the placement of their pitches as well, at least as they start. This is a good time to work on tunneling – the technique where all pitches start out on the same path (like they’re going through a tunnel) and then break in different directions.

The closer the tunnel can start to the middle while leaving the pitches effective, the more likely they are to be called strikes if the hitter doesn’t swing.

On the other side of things, it’s more important than ever for hitters to learn where the umpire’s strike zone is and how he/she is calling certain pitches. If it’s based on where the catcher’s glove ends up, stand at the back of the box, which makes pitches that may have missed by a little at the plate seem like they missed by much more when they’re caught by the catcher.

If the umpire isn’t calling the edges, you may want to take a few more pitches than you would ordinarily. Just be prepared to swing if a fat one comes rushing in. On the other hand, if the umpire has widened up the zone, you’d best be prepared to swing at pitches you might ordinarily let go.

Things aren’t exactly ideal right now, but at least you’re playing ball. At least in most parts of the country.

Softball has always been a game that will break your heart. This is just one more hammer in the toolbox.

Accept it for what it is and develop a strategy to deal with it – at least until the Blues are able to get back to their natural habitat. You’ll find the game is a lot more enjoyable that way.

Shoes photo by Karolina Grabowska on Pexels.com

Today’s Goals Are Tomorrow’s Disappointments

Setting goals is an important part of any sort of development, athletic or otherwise. Without them, it’s easy to meander your way through life. As the Cheshire Cat told Alice during her adventures in Wonderland, “If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there.”

One phenomenon that isn’t often spoken of, however, is what happens to us mentally after a goal has been met. It’s amazing how it can turn around.

I’ve seen this particularly after I started setting up a Pocket Radar Smart Coach for virtually every pitching lesson. Each pitch thrown is captured, and the result is displayed on a Smart Display unit in bright, red numbers.

I call it my “accountability meter” because it shows immediately if a pitcher is giving anything less than her best effort. A sudden dropoff of 6 mph is a very obvious indication that a pitcher was slacking off on that particular pitch.

Here’s the scenario I’m addressing. Let’s say a young pitcher is working hard trying to move from throwing 46 mph to 50 mph. She’s been practicing hard, working on whatever was assigned to her, and slowly her speed starts creeping up.

She gets up as high as 49 once, but then falls back a bit again. She knows she can do it.

Then the stars align and voila! The display reads 50. Then it does it again. And again.

There are big smiles and a whoop or two of triumph! Goal met! Pictures are taken and high fives (real or virtual) are exchanged.

A few weeks later, the pitcher continues her speed climb and achieves 52. Once again, celebrations all around and she starts looking toward 60 mph.

The next lesson she throws a bunch of 50s, but can’t quite seem to get over that mark. What happens now?

Is there still the elation she had just a few weeks before? Nope. Now it’s nothing but sadness.

That 50 mph speed that once seemed like a noble, worthy goal is now nothing but a frustrating disappointment.

That would be the case for Ajai in the photo at the top. She was all smiles when we took this picture a couple of months ago. But if that was her top speed today she would be anything but happy.

But that’s ok, because it’s all part of the journey. We always want to be building our skills; goals are the blocks we use to do it.

But once they have been met, they are really of no more use to us. Instead, they need to be replaced with bigger, better goals. That’s what drives any competitor to achieve more.

So yes, today’s goals will quickly become tomorrow’s disappointments. But that’s okay.

Remember how far you’ve come, but always keep in mind there is more to go. Stay hungry for new achievements and you just might amaze yourself.

Big Issues Don’t Always Require Big Solutions

Toward the end of the summer 2020 season (if you can call that a season), one of my pitching students, a terrific lefty named Sammie, developed some control trouble. Suddenly, out of nowhere, she started throwing everything off the plate to her throwing hand side.

We got together and we worked on it. I thought she might be going across her body instead of straight so we set up a couple of giant cones to try to steer her back down the straight and narrow as it were.

It helped a little, but not enough. She still struggled in her next game, and in her practice sessions.

This was definitely a problem that needed to be corrected so I racked my brain on what the probable root cause might have been. As it turned out, however, I didn’t need to think so hard.

I simply needed to remember my own advice, given about a year ago, regarding Occam’s Razor: If there is a simple solution and a complex one, the simple solution is usually the best.

In this case, I only needed to remember the opening song from “Les Miserables” – look down.

When I looked down at Sammie’s feet on the pitching rubber I knew exactly what the problem was. She was like this:

We have been working on her sliding her foot over the center of her body and I thought she had that down. But somewhere along the way she stopped centering, and instead would only slide her foot slightly. As a result, everything was going down the left side, often off the plate.

So we worked once again on the proper slide across, placing her left foot more in this position before driving off:

Once she got her foot more in this position all her problems with being off the plate went away, as if by magic. Control was regained and she once again began dominating hitters.

So there’s the lesson for today. Sometimes a pitcher’s (or any athlete’s for that matter) issues aren’t being driven by some horrible breakdown in mechanics.

As we coaches work to acquire knowledge and hone our craft, we can get caught up in over-thinking the issues and the solutions. This is a good reminder that often a simple adjustment on a pitcher who has been doing well can get her right back on track.

William of Ockham may have been born in 1287. But he would have made a heck of a pitching coach.

“Hip Eye” Helps Encourage Driving the Back Side When Hitting

A few weeks ago I wrote about a cue I’d developed called “shoulder eye.” It’s worth reading the full post, but if you’re pressed for time the core concept is placing an eye sticker on the shoulder, then making sure the shoulder comes forward to see the ball before it tilts in.

Then last week I ran into another issue where the eye stickers came in handy.

In this case it was a fairly new student who was having some challenges getting the hang of driving her back hip around the front side to initiate her swing. She’d done fine off the tee, but when we moved to front toss she just couldn’t help but lead with her hands as she has since she started playing.

So… off to my bag of tricks I went, and I came back with an eye sticker. I told her to place it on her back (in this case right) hip. (If you look closely at the top or the full-length photo you can see it.)

I then told her that in order to hit the ball, she had to make sure her “hip eye” came around to get a good look at the ball before starting her hands.

As with shoulder eye I’m not 100% of why this works. But I’m happy to report that it does.

My guess is that placing the eye on the hip (or shoulder) creates more of a, pardon the pun, visual for the hitter. Perhaps “bring your hip around” is too vague, whereas point this eye toward the ball first is more specific.

Or it could just be goofy enough to break well-established, unconscious thought patterns to enable new information to take over.

In any case, it seems to work. I’ve used it a couple of times since that first one and the difference was immediate.

The hitter wasn’t necessarily perfect – I like a lot of drive out of the back side. But it definitely set her down the right path.

So if you have a hitter who is having trouble latching onto the proper sequences of hips-shoulders-bat, or who isn’t using her hips at all, get some eyeball stickers and have her place it on her back hip. It might be just what she needs to start hitting with authority.

Are We Destroying Our Kids?

Injuries have always been a part of participating in youth sports. Jammed fingers, sprained ankles and knees, cuts requiring stitches, even broken bones were an accepted part of the risk of playing. Things happen, after all.

Lately, though, we are seeing a continuing rise of a different type of injury. This one doesn’t happen suddenly as the result of a particular play or miscue on the field. Instead, it develops slowly, insidiously over time, but its effects can be more far-reaching than a sprain, cut or break.

I’m speaking, of course, about overuse injuries.

According to a 2014 position paper from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, roughly 46 to 54% of all youth sports injuries are from overuse. Think about that.

There was no collision. There was no tripping over a base or taking a line drive to the face. There was no stepping in a hole in the outfield or catching a cleat while sliding. The injury occurred while participating normally in the sport.

And here’s the scary part. As I said, this report came out in 2014. In the six years since, the pressure to play year-round, practice more, participate in speed and agility training and do all the other things that go with travel ball in particular has only gotten worse.

You can see it in how one season ends and another begins, as we recently went through. Tryouts keep getting earlier and earlier, with the result that players often commit to a new/different team before their finished playing with their current teams.

It’s not that they’re being bad or disloyal. It’s that they have no choice, because if they wait until the end of the current season there won’t be anywhere left to go because all the teams have been chosen.

What is even crazier is that there literally was no break for many players from one season to the next. I know of many for whom their current season ended on a weekend and their first practice for the next season was the week immediately after. Sometimes they were playing their first game with the new team before their parents had a chance to wash their uniforms from the old team.

And it wasn’t just one practice a week. Teams are doing two or three in the fall, with expectations that players will also take lessons and practice on their own as well.

That is crazy. What is so all-fired important about starting up again right away?

Why can’t players have at least a couple of weeks off to rest, recuperate physically and mentally, and just do other things that don’t require a bat, ball or glove? Why is it absolutely essential to begin playing tournaments or even friendlies immediately and through the end of August?

I think what’s often not taken into consideration, especially at the younger ages, is that many of these players’ bodies are going through some tremendous changes. Not just the puberty stuff but also just growth in general.

A growth spurt could mean a reduction in density in their bones, making them more susceptible to injuries. An imbalance in strength from one side to the other can stress muscles in a way that wouldn’t be so pronounced if they weren’t being used in the same way so often.

Every article you read about preventing overuse injuries stresses two core strategies:

- Incorporating significant periods of rest into the training/playing plan

- Playing multiple sports in order to develop the body more completely and avoid repetitive stress on the same muscles

When I read those recommendations, however, I can’t help but wonder: have the authors met any crazy softball coaches and parents?

As I mentioned, I’ve seen 12U team schedules where they are set to practice three times a week – in the fall! And these aren’t PGF A-level teams, they’re just local teams primarily playing local tournaments.

Taking up that much time makes it difficult to play other sports. Sure, the softball coach may say it’s ok to miss practices during the week to do a school sport, but is it really?

Will that player be looked down on if she’s not there working alongside her teammates each week? Probably.

Will that player fall behind her teammates in terms of skill, which ultimately hurts her chances of being on the field outside of pool play? Possibly.

So if softball is important to her, she’s just going to have to forego what the good doctors are saying and just focus on softball, thereby increasing her risk of an overuse injury.

This is not just a softball issue, by the way. It’s pretty much every youth sport. I think the neverending cycle may be more of a softball issue, but the time factor that prevents participation in more than one sport at a competitive level is fairly universal.

In the meantime, a study published in the journal Pediatrics that pulled from five previous studies showed that athletes 18 and under who specialize in one sport are twice as likely to sustain an overuse injury than those who played multiple sports.

The alarm bells are sounding. It’s like a lightning detector going off at a field but the teams deciding to ignore it and keep playing anyway. Sooner or later, someone is going to get struck.

What can you do about it? It will be tough, but we have to try to change the culture.

Leaders in the softball world – such as those in the various organizations (including the NFCA) and well-respected college coaches – need to start speaking up about the importance of reducing practice schedules for most of the year and building more downtime in – especially at the end of the season. I think that will help.

Ultimately, though, youth sports parents and coaches need to take responsibility for their children/players and take steps to put an end to the madness. Here are a few suggestions:

- Build in a few weeks between the end of the summer season and beginning of the fall season for rest, recovery and family activities. There’s no reason for anyone to play before Labor Day.

- Cut back on the number of fall and winter practices. Once a week with the team should be sufficient. Instead, encourage players to practice more on their own so they can fit softball activities around other sports and activities.

- Reduce the number of summer games/tournaments. Trying to squeeze 100+ games into three months in the summer (two for high school players who play for their schools in the spring season) is insane bordering on child abuse. Take a weekend or two off, and play fewer games during the week.

- Plan practices so you’re working on different skills in the same week. This is especially important when it comes to throwing, which is where a lot of overuse injuries occur. Work on offense one day and defense another. Or do throwing one day and baserunning another. Or maybe even play a game that helps with conditioning while working a different muscle group.

It won’t be easy, but we can do this. All it takes is a few brave souls to get it going.

Overuse injuries are running rampant through all sports, including fastpitch softball. With a little thought and care, however, we can reverse that trend – and keep our kids healthier, happier while making them better players in the process.

Photo by Karolina Grabowska on Pexels.com

The 3D Printer Approach to Softball Success

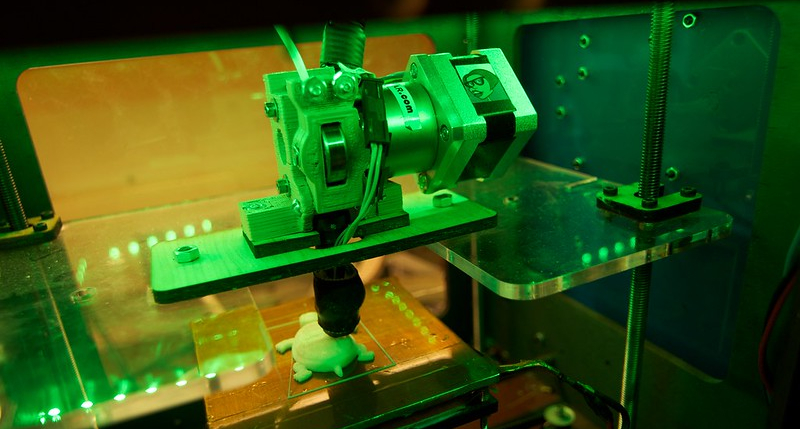

A few years ago, one of my day job clients took me out back onto the shop floor to show me this cool new technology they were using to create prototypes of products in development.

“It’s a 3D printer,” the client told me. “We program in what we want based on CAD drawings, and then it produces a complete sample, down to every nook and cranny.” Then she showed me how it worked.

Basically, the head on the printer would slide along at high speed, depositing thin layer after thin layer of plastic (or whatever substance they used). At first, it looked like an indistinguishable blob, but slowly, over time, whatever it was they were making began to take shape until a finished product finally came out.

That is very similar to the way building a successful softball player works. You start out with some raw materials and an idea of what the finished product will be. But then you have to build the player, layer by layer, which takes time and patience.

I think it’s the second half of that equation – patience – that tends to make people stop the “machine” before the finished product is created. These days in our instant-everything world, everyone wants what they want right the heck now.

They don’t want to put in hours and hours of practice just to realize a slight improvement, such as adding one mile an hour as a pitcher or hitting the ball another 20 feet as a batter. They want a magic drill or technique that will enable them to go from throwing 48 mph to 60+ mph in a couple of weeks, or turn them from a .225 hitter to a .440 hitter with an OPS over 1.0.

That would be nice, but it simply doesn’t work that way. As I always say, if I could make you a star in one lesson every lesson would cost $1,000 and there would be a line a mile long down the street to get that lesson.

Instead, you have to operate like the 3D printer. If you stand there and watch it as it works, you’re likely to get bored and maybe fall asleep. It just keeps on grinding away.

Over time, however, it produces something beautiful and useful. Of course, if all you see is the end product you have no idea how much work, how many passes of the print head went into it. You can just admire the result.

It’s the same with players. If you just look at the player shining on the field you have no concept of the number of pitches, swings, ground balls, fly balls, etc. that player did before you ever saw the bright, shiny player she is now.

I know, because I’ve seen it. Parents will tell me how funny it is when someone says about their daughter, “Wow, it must be nice to be so talented that it just comes naturally to her.”

Those people making that comment weren’t there when that same girl was sitting on the bench because her coaches didn’t think she was good enough to be on the field. They weren’t there when she struggled to get a hit, or to find the plate when she was pitching, or making awful errors on easy fielding plays. They weren’t there when she left a practice or lesson on the verge of tears because she couldn’t quite get a skill.

But they also weren’t there when she was in the back yard throwing pitches or hitting off a tee into a net, determine to get better. And get better she did, little by little, layer by layer, until her skills equaled and then surpassed her less-dedicated teammates and she came into her own.

It’s easy to look at who a player is today and assume that’s always who she has been – i.e., she has always been a star. But more often than not, most great players have a story of struggle to share.

The key, however, is understanding that any deficiencies someone may have now don’t have to define who they are in the future. With a fair helping of dedication and determination, along with a little knowledgeable guidance, players can build their skills, mental approach and confidence to become the fastpitch softball players (and people) they are meant to be.

Now I’d like to hear from you. Please share your stories in the comments of your daughters, or kids you’ve coached, who may have started out on the low end but eventually went on to great softball success.

Oh, and here’s a cool time lapse video of some things being made with a 3D printer.

3D printer photo © 2011 Keith Kissel.

Book Review: Spanking the Yankees – 366 Days of Bronx Bummers

AUTHOR’S NOTE: While technically this post isn’t about fastpitch softball, I know many softball coaches, players, parents and fans are also followers of our sport’s older, slower cousin so once again I diverge slightly from the usual path to bring you what I’m sure many will find to be a fun read.

There is probably no sports franchise that is more storied than the New York Yankees. Love ’em or hate ’em (and there are plenty on both sides) you have to admit that they have long been considered the Gold Standard for success.

In fact, often the best or most dominant teams in other sports are referred to as “The New York Yankees of (FILL IN THE BLANK).”

With all that adoration/hype, it’s tempting to believe the myth that the Yankees have achieved this rarefied status by being able to avoid the missteps, boneheaded plays, under-performing superstars and other issues that plague the rest of the league.

“Spanking the Yankees – 366 Days of Bronx Bummers” by Gabriel Schechter busts that myth wide open. It turns out they’ve made just as many untimely errors, had as many failed saves and critical strikeouts, secured as many draft day and free agent busts, and suffered through as many poor management decisions (looking at you George Steinbrenner) as anyone else. They’ve just managed to win 27 World Series rings in spite of it all.

The author makes no bones about his point of view or reason for writing the book; he has hated the Yankees his entire life, and thus takes particular delight in documenting every misstep in the 318-page tome. Yet you can also detect his grudging respect for what the Yankees have accomplished since they began to play more than 100 years ago.

(Full disclosure: I am a lifelong Chicago Cubs fan, so when my Yankees-loving friend Ray Minchew complains that the Yankees haven’t won a World Series in eight years I have zero sympathy for him. That’s the perspective I come from.)

The book is actually a quick and easy read. It is set up like a journal, walking readers through a day-by-day accounting of the worst thing that happened to the Yankees on a particular day, regardless of the year. Here’s an excerpt from May 8, 1990:

The Yankees lose to the A’s for the fifth time already this season, a 5-0 pasting in Oakland. “This is tough,” admits Yankees manager Bucky Dent. “I’ve never seen anything like this.” Get used to it, Bucky. The A’s sweep all 12 games from the Yankees this season, outscoring them 62-12 in the process (0-2-0-1-0-1-0-1-1-1-2-3). On second thought, Bucky, never mind. Four weeks later, he is liberated from his Bronx bondage, ending his managing tenure with a record of 36-53. Some guy they call “Stump” takes his place, and the Yankees finish dead last in their division with a 67-95 record.

Hilarious.

This short format, by the way, makes it ideal for bathroom reading, airplanes and other travel, waiting rooms and other places where you need to be able to get into and out of it easily. Although once you get hooked you’ll probably want to keep going anyway.

Its three sections begin with Opening Day (which occurs on different days) and the regular season, followed by postseason play (with loving emphasis on World Series losses – yes the Yankees have lost more World Series than most teams have played in) and then the offseason. Anecdotes go all the way back to the days when the Yankees were known as the New York Highlanders and played at the Polo Grounds.

So by now you’re probably thinking this is a great gift for a Yankees-hater or the casual baseball fan. You might also want to pick it up to needle your Yankees-loving friend. But funny thing about that.

The Yankees fans I know have a love-hate relationship with the ballclub, and they like to wallow in the misery as much as anyone else.

Yankees fans may actually find the book cathartic, opening up old wounds and letting them once again wonder why certain players never seemed to come through in the postseason, why a particular manager couldn’t handle a bullpen very well, why management paid so much for a free agent that was a star before and after their time in New York but was a total bust while wearing pinstripes and about dozens of other issues that have made their blood boil through the years.

If you love baseball, love or hate the Yankees, or just want a quick, fun read to take your mind off of whatever is bothering you in your real life, give “Spanking the Yankees” a look. I think you’ll find it’s time well-spent.

For Better Hitting, Use Your Shoulder Eye

While it might sound like this is a post specifically for mutants, “shoulder eye” is a concept I came up with to help hitters stop dropping their back shoulders toward the catcher before they begin to rotate their hips to fire the swing. The premise is you want the imaginary eye on your shoulder to turn and get a look at the ball before you start to tilt into the swing.

This is an issue I see all the time, especially on low pitches. As soon as a hitter spots that the pitch is low, he/she will start dropping the shoulder to get down to the ball. That’s just wrong on so many levels.

For example, if you drop the shoulder back and down instead of bringing it forward first you lose the ability to fully adjust to pitch locations. You’re kind of locked into a zone, and if you guessed wrong there isn’t much you can do about it except swing and miss or hit a weak ground ball or popup.

If you turn first, keeping the shoulder up, you can then take a little more time (even if it’s just a couple hundredths of a second, everything helps) to see where the ball is, then tilt only as much as is needed. You can work from high to low, enabling you to cover more of the strike zone AND get a better bat angle.

Another issue with dropping back is that it tends to restrict your ability to move the hips forward effectively. All your weight is pressing down on your back side making it difficult rotate quickly and efficiently. Even if you get your hips to turn you won’t be generating much power out of them.

If you turn your shoulder eye forward first, you can unweight your back side so it can drive quickly around your front side and generate power. You can then get a proper hips-shoulders-bat swing that will help you drive balls into the gap or over the fence rather than seeing most of your contacts end up staying in the infield.

The idea of not dropping the back shoulder toward the catcher before rotation isn’t new, by the way. It’s a fairly standard instruction.

Hitters are told to land with their front shoulder lower than the back, turn a certain way, and do all sorts of other things. But they don’t always understand the instruction in a way that makes it easy to execute.

The shoulder eye concept does. Telling a hitter he/she has an eye on the shoulder, and it has to look forward before the shoulder drops, is visual (no pun intended) and easy to understand.

Originally I would tell hitters just to visualize the shoulder eye. But then one day it occurred to me – why not give them an actual shoulder eye?

A few bucks on Amazon later I had enough stickers to teach a small army of hitters. With 4,000 of them I’m guessing it’s a lifetime supply, even with my habit of giving a few to hitters who want to use them at home or at practice as well.

And why not? It’s fun and effective. Even my students who are college players like the stickers and find the concept valuable in helping them hit bombs.

So if you have a hitter who just loves to drop that back shoulder and sit on the back side, open his/her eyes to the shoulder eye. In my experience it’s a real difference-maker.