Author Archives: Ken Krause

For the Love of Gaia, Please Stop Teaching Screwballs to 10 Year Olds

There is a phenomenon I’ve noticed lately in my area and seemingly is happening across the country as I speak with other pitching instructors.

When I start lessons with a new pitcher I will ask her what pitches she throws. For pitchers under the age of 14 my expectation is fastball, change, and maybe a drop ball.

These days, however, I have been shocked at how many, even the 10 year olds, will include a “screwball” in their list of pitches. Especially when I then watch them pitch and they struggle to throw their basic fastball with any velocity or semblance of accuracy.

Who in the world thinks teaching a screwball to a 10 year old (or a 12 or 13 year old for that matter) is a good idea? Particularly the screwball that requires the pitcher to contort her arm and wrist outward in a twisting motion that includes the “hitchhiker” finish?

There is simply no good reason to be doing that. For one thing, most kids at that age have rather weak proprioception (body awareness of self movement), which means they often struggle to lock in a single movement pattern.

So, since the way you throw a screwball is in direct opposition to the way you throw a fastball (especially with internal rotation mechanics but it’s even true of hello elbow pitchers) why would you introduce a way of throwing that will interfere with development of core mechanics? Pitchers who are trying to learn both will be splitting their time between two opposing movements, pretty much ensuring they will master neither.

Then coaches and parents wonder why the poor kid can’t throw two strikes in a row in a game.

Just as important is the health and safety aspect of twisting your forearm and elbow against the way they’re designed to work. As my friend and fellow pitching coach Keeley Byrnes of Key Fundamentals points out, “Boys at that age are cautioned against throwing curve balls with a twisting action because of the stress it places on their elbow joints. Why would you encourage a softball pitcher to do the same thing?”

Keeley also points out that most 10 year olds don’t hit very well anyway, so developing a screwball at that age is unnecessary. You can get many hitters out by throwing a fastball over the plate with decent velocity (which means it’s not arcing in).

Tony Riello, a pitching coach, trainer, and licensed doctor of chiropractic, is also concerned about the effect throwing the twisty screwball can have on other body parts. He says, “To be that spread out left to then force the arm and shoulder right seems not healthy for either the back or the shoulder,” he says.

Then there’s the fact that in 99% of the cases a screwball isn’t really a screwball. It’s just a fastball that runs in on a hitter.

Why do I say that? Because if you look at the spin on 99% of so-called screwballs, especially among 10 year olds but even at the collegiate level, they don’t have the type of spin that would make them break. They have “bullet” spin, i.e., their axis of spin is facing the same direction as the direction of travel.

For a screwball to actually be a screwball the axis of spin would need to be on top of the ball, with spin direction going toward the throwing hand side. Just as a curve spins away from the throwing hand side.

So if you’re throwing a pitch that isn’t going to break anyway, why not just learn to throw an inside fastball instead? If you want it to run in a little more, stride out more to the glove side then let it run itself back in.

But again, you’re now giving that young pitcher who’s just trying to learn to throw the ball over the plate two different mechanics (stride straight, stride out) to use, which means she’s probably going to be half as effective on either one.

Oh, and that hitchhiker move that’s supposedly the “key” to the screwball and places all the stress on the elbow? It happens well after the ball is out of the pitcher’s hand, so it has no impact on the spin of the pitch whatsoever. Zero. None. Nada.

Finally, and perhaps most important, once a young pitcher can throw with decent velocity and locate her pitches (or at least throw 70% strikes) there are simply better pitches for her to learn first.

After the basic fastball, in my opinion (and in the opinion of most quality pitching coaches), the second pitch that should be learned is a changeup that can be thrown with the same arm and body speed as the fastball but resulting in a 10-15 mph speed differential. Throwing both the fastball and change at the right speeds for 70% strikes should be enough to keep the typical 10- or 12-year old pitcher busy for a while.

Next you would want to add a drop ball. The mechanics of a properly taught drop ball are very similar to the fastball. In fact, I like to say they are fraternal twins.

Making a ball drop at the right spot, especially given so many young hitters’ desire to stand up as they swing, will get you a lot more outs, either as strikeouts or groundouts. A good drop ball will still translate into more groundouts as you get older too – just ask Cat Osterman.

From there it’s a little less certain. You can go either rise ball or curve ball. I usually make the decision based on the pitcher’s tendencies.

A well-thrown rise ball is still an extremely effective pitch, even though it doesn’t actually break up. And a well-thrown curve will actually break either off the plate (traditional curve) or back onto it (backdoor curve). Either way it moves – unlike the screwball which mostly travels on the same line.

I would save the screwball for last – unless you happen to play in an area where slappers are predominant in the lineup. Which in the era of $500 bats and quality, year-round hitting instruction is about as scarce as screwballs that actually change direction.

There are simply better pitches to learn. And if you do work on a screwball, there are better ways to learn it than trying to twist your wrist and forearm off in a contorted move that should be outlawed by the Geneva Convention.

The bottom line is that, for the love of Gaia, there is no good reason to be teaching a screwball to a 10 year old – or any pitcher who hasn’t mastered her fastball and changeup first. Let’s make sure we’re giving our young pitchers the actual tools they need to succeed – and avoid those that can lead to injury and perhaps a career cut short.

It Always Helps to Have Perspective

One of the things I often tell players on their development journey is that yesterday’s achievements eventually become today’s disappointments.

For example, when a player first comes for hitting lessons she may be striking out all the time. Which means her goal is to not strike out so often, i.e., hit the ball instead.

She works hard and starts hitting regularly. Then she has a streak where she hits the ball but right at someone and she’s out every time.

She is still achieving the original goal – not striking out – but the goalposts for her expectations have moved and now anything less than a hit is a disappointment.

Probably the easiest place to see it, however, is with speed measurements for pitchers. Everyone always wants to get faster. I’m sure Monica Abbott, who I believe still throws the hardest out of all female players, would still love to add an mph or two if she could.

So pitchers work hard to achieve a new personal record. Then another. Then another, etc.

After a while, though, that first personal record she got so excited about is now a disappointment and perhaps even feels like a step backwards.

That’s why it helps to keep some perspective on the longer journey instead of just the next step.

That idea came home to roost last night when I was giving a lesson to a student (Gianna) who hasn’t been to lessons in a couple of weeks due to a volleyball-related thumb injury. (Don’t even get me started on how volleyball injuries impact softball players!)

Now, as you know the thumb is pretty important for gripping things like softballs. In fact, the opposable thumb is one of the key advantages that separates humans and other primates from most of the rest of the animal kingdom.

Gianna’s thumb had swollen up pretty badly and for the last couple of weeks she’d had trouble gripping anything. The swelling had finally gone down, and with a tournament coming up and her team already short a couple of other pitchers due to volleyball injuries (grrrr) she wanted to do all she could to help them.

So with her thumb stabilized and a bandage that wrapped around her wrist she decided to give it a go to see if she could pitch this weekend.

The short answer was yes, she could. But her speed was a little down from where it normally is. That’s ok, though, she was able to do it without pain (so she said) and to throw all her pitches.

Later on when I thought about the speed being down I had an epiphany.

You see, a year ago Gianna was struggling with some mechanical issues that were preventing her from getting the type of whip and pronation that would bring her speed up. She was working very hard to correct them but once those bad mechanics have set in the habits they create can be tough to break.

(One more piece of evidence that saying “Start with hello elbow and you can change later” is bad, bad advice.)

As I thought about it I realized that had she been throwing the speed she was averaging last night at this time last year, she would have been very excited and gone home on cloud nine. Because it was about 3 mph higher (whereas now it was 2-3 mph slower).

And that’s the point. Sometimes in our quest to get to “the next level” we sometimes forget to take a minute and look at how far we’ve come.

Keeping that longer-term perspective can help you stay positive when you hit the inevitable plateau and keep you going until you reach your next achievement.

Spice Up Your Games with Some “Trick” Plays – Part One

As about every third online ad tells us, we are in the middle of pumpkin spice season.

Now, for those who love it this is the best time of the year, at least culinary-wise. And for those who hate it (there doesn’t seem to be any middle ground on this), hang in there; the holidays and all their sweet goodies are just around the corner.

I think what those who are into it (including me and especially my daughter Stefanie) love about pumpkin spice season is that it’s something a little different.

We might not be so excited about it if it was available all year long. But since it’s outside the norm we can definitely appreciate it when it comes along.

Which brings us in a roundabout way to today’s topic: “trick” plays on defense and offense in fastpitch softball.

I am definitely a proponent of getting your fundamentals together first. It is absolutely critical for individuals and teams to learn how to field routine ground balls, make simple throws, cover bases, run the bases, swing the bat, etc. with near-100% reliability.

If you can’t do the fundamental things, no amount of trick plays is going to save you.

But if you can do those things, having a few trick plays in your arsenal can not only spice up practices and get your players pumped during games, they can also help you turn the momentum of a game around.

Following are a few of my favorites. Today’s post is focusing on defensive plays. Next week we’ll look at some on offense.

You can pick and choose one or two you think your team might like and be able to handle. Or you can try to incorporate them all to help you get out of a jam – or put the other team in one.

Again, just be sure you don’t spend so much time on them in practice that you neglect the fundamentals. It doesn’t take much to get the wheels to fall off the wagon – at which point the townspeople (parents) will be coming for you with torches and pitchforks.

Defensive Trick Plays

Third Base Sucker Play

My formers players will recognize this one as “code blue” or just simply blue. It’s great for getting a critical out in a tight game with minimal risk.

The situation is there is a runner on third with fewer than two outs and it’s important that the runner on third doesn’t score. It should be a called play so everyone on the defense is prepared for what happens.

If a ground ball is hit to the third baseman (or the pitcher if the pitcher is a good fielder, or dropped right in front of the catcher), the fielder picks up the ball, LOOKS THE RUNNER BACK, then pretends to throw to first. Looking the runner back is critical to convincing her that once the fielder turns toward first she will throw.

Only she doesn’t. She pulls the ball down and immediately spins around to see where the runner on third is.

If she bites on the fake throw and takes off for home, the fielder can either tag the runner or get her into a rundown. If your team is any good at rundowns they should get the out while erasing a scoring threat from 60 feet away.

(The counter on this for the offense, by the way, is for the batter/runner to keep running as soon as she realizes the defense is focused on the runner on third. If she’s fast enough, or the runner on third stays alive long enough, she might even go all the way to third figuring the original runner on third will be out sooner or later anyway.)

You want to run this against an aggressive baserunning team – the type that is looking to take advantage of every opportunity to score. It doesn’t work so well against the cautious, the slow, or the ones who just don’t pay attention.

If you are worried about the ball slipping out of the fielder’s hand on the fake throw, have her keep the ball in her glove and throw with an empty hand. At most levels the runner is looking at the arm motion, not whether the fielder has a ball in her hand, and will go as soon as the throwing motion is complete.

Third Base Sucker Play with Real Throw

Ok, so your opponent got fooled once, either in this game or another, and has cautioned their runners to make sure of the throw before taking off from third. Does that mean you’re done?

Not at all. Same situation – aggressive runner on third with fewer than two outs.

This one works best on a ball hit to the third baseman, and again presents minimal risk.

When the ball is hit, the third baseman fields the ball, looks the runner back, and proceeds to throw it to the first baseman. Except the first baseman isn’t at first base; she is halfway up the first base line, in the perfect position to begin a rundown.

It’s rare that anyone pays attention to where the first baseman is, or where the throw is pointed. From the runner’s (and third base coach’s) point of view, the throw from the third baseman is going toward first.

It isn’t until the rundown starts that they realize it didn’t. Again, if your team is good at rundowns it should result in an out (versus just holding the ball, which will rarely produce an out), but worst case it will prevent the runner from scoring.

Pickoff to Third

For this one you need a catcher who has a quick transfer and is good at throwing from her knees. And by good I mean she not only throws hard but is accurate.

Most coaches will teach their baserunners on third to lead off as far as the third baseman. Makes sense, because the closer they can get to home the better chance they have to score on a ground ball.

You can take advantage of that. When the ball is pitched, assuming it’s not hit the catcher makes and immediate transfer and quick throw to third.

The third baseman gets the ball and immediately sweeps a tag to her right, preferably all in one motion. The suddenness of the moves can catch a runner napping and allow her to be tagged before she can react. And the presence of a right-handed batter helps cover the catcher’s movements, making it hard to tell that she’s throwing down to third.

If you execute it well it can be a game-changer. One time I was coaching a game where we were clinging to a one-run lead.

In the seventh inning the leadoff batter on the other team hit a triple, completely changing the momentum of the game. But we ran this play and she never even moved. Got the out, wiped her off the board, and the momentum shifted back to us for the win.

Understand, though, this can be a medium-to-high risk play. Because if your catcher chucks the ball into left field instead of to the third baseman, well, see the graphic above.

But if you do it right it’s a thing of beauty.

Pick Behind the Runner at First

This is a great way to get a quick out in a tough situation, such as when bases are loaded. The lowest-risk version is when there are two outs, because if you execute it successfully you’re out of the inning.

But you can run it on any number of outs, especially if you’re willing to trade an out for a run.

As I said, the situation is bases are loaded. You notice that the runner on first is taking a decent leadoff but not really paying attention to what happens after the pitch if the ball isn’t hit.

For example, she drops her head and turns around to walk back to the base figuring no one is paying attention to her.

For this play you want to have your first baseman move up the line so the runner (and first base coach) figure the runner is totally safe. You call an outside pitch so the catcher is moving a bit toward first and the hitter doesn’t hit it.

That last part is important because as soon as the pitch is thrown and all eyes are on home, the second baseman is going to sneak in behind the runner to cover first. The catcher then throws down immediately to first, the first baseman gets out of the way, and the second baseman places the tag. She may even have to walk out to the runner to do it because the runner is so shocked (I’ve seen it happen).

There is a risk, of course, of the catcher chucking the ball into right field and allowing one or even multiple runners to score. But if you work at it you can pull this one off and have some fun doing it.

Sneaky Catcher Pick to First

This is a variation of the last play. It relies a lot on deception and definitely requires a catcher to practice it diligently. But again you can catch a runner napping pretty easily if you can execute it.

The lowest-risk situation is bases loaded with two outs to prevent the runner on first from just taking off. But you can do it in a first-and-third situation if you think either the runner on third won’t go on the throw or she’s slow enough that you can recover if she does.

Here’s how it works. The pitch is thrown, the catcher receives it, and she starts running the runner on third back to the base.

Once that runner goes back, the catcher CASUALLY turns toward the pitcher and takes a step toward her to throw. She also looks right at the pitcher – all’s quiet on the Western Front.

But instead of throwing back to the pitcher, she opens her shoulders a little more and fires to first without ever looking. If it is done correctly it will catch the runner and first base coach off-guard enabling an easy tag.

Of course, done incorrectly it will either tip off the runner to hurry back or sail into foul territory in right field starting up the merry-go-round of baserunners.

This is why catchers have to spend some quality time learning to make this no-look, awkward throw. But if they can learn to do it properly they can catch a baserunner even if she knows it’s coming. I’ve seen it happen.

Continuation Play

This is one of those things that I’m sure most coaches love when their teams do it and are really annoyed when other teams do it. You know the one.

There is a runner on third and the batter walks. She starts trotting down to first base, and as she gets there she takes off for second base.

Your team is confused, you as a coach are embarrassed, and your opponents now have runners at second and third.

How bad it actually is kind of depends on your team’s skill and level of play. In many cases it’s not really that bad because the batter/runner was just going to steal second on the next pitch anyway. It just made you look bad that she did it.

But if you do want to try to prevent it you have a couple of options.

The first is to have your catcher throw the ball to the first baseman instead of the pitcher when the walk occurs. The first baseman then stands between first and second so if the runner tries to go she will be tagged out immediately.

She just has to keep an eye on the runner on third (and be able to make a good throw home if she goes).

The second is to have your pitcher walk to the back of the circle with the ball and stand there. Your shortstop then covers second and your second baseman stands about 10-15 feet to the first base side of second.

Under the Look Back rule, once the ball is in the circle and the batter/runner reaches first, the runner on third either has to go forward or go back. This is providing the pitcher doesn’t make any moves toward either runner.

If the batter/runner takes off for second, the pitcher waits until the batter/runner is fairly close to the second baseman and then turns to throw. In the meantime, the catcher is laser-focused on the runner on third in case she decides to take off, which she can do once the pitcher turns toward the batter/runner.

If the runner on third stays put the second baseman puts the tag on the batter/runner. If the runner on third tries to score, the second baseman starts running in to get a rundown started and throws ahead of the runner if necessary. If she can put the tag on the batter/runner first even better.

There are a few variables in play here. For example, if your team is up by a few runs forget the runner on third and get the batter/runner.

The same goes for if there are two outs and you can get the batter/runner quickly, before the runner on third scores.

But in a close game the runner on third remains your priority. Even if you don’t get the out at second this time you’ve at least given the other team’s coach something to think about.

The Dreaded First and Third Situation

In this situation there are runners at first and third with fewer than two outs. You know the other team is going to try to move that runner on first up to scoring position and you’d like to get her out if you can. But you need to keep the runner on third from scoring too.

There are a few different plays you can try. One is the fake throw from the catcher. It doesn’t work most of the time but if you have an aggressive (and probably inexperienced) runner on third she may fall for it.

You can also try just throwing the runner out at second. Teams have gotten so good about being aware of the runner at third and trying to fake her into running into an out that most are pretty cautious these days.

That hesitation can cause her not to run, even if you do throw.

But if you really want to play with the big kids here’s what you do. On the steal, the shortstop goes to cover second and the second baseman moves up to a cut position between the pitcher’s rubber and second base.

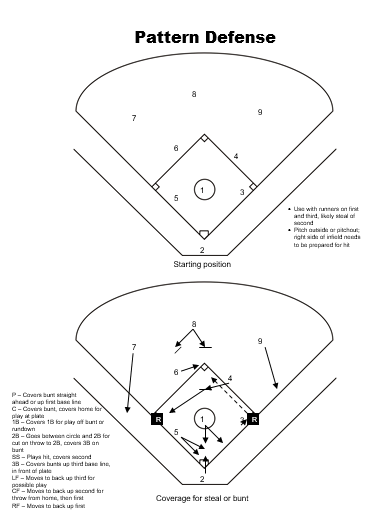

This is sometimes called a “Pattern Defense.” Here’s a diagram to help make it clearer.

The catcher throws down to try to throw out the runner going from first to second. You now have a couple of options.

The easier, safer play is that the second baseman steps in to cut the ball off as a planned play. If the runner on third takes off she throws home and either a tag or rundown ensues. If not the runner stole second just as if you did nothing.

The bigtime play is that the second baseman ONLY cuts the ball if the runner on third takes off for home. This requires someone to keep an eye on the runner on third and to call it out if she’s going.

A logical choice is the third baseman but it could also be the first baseman. Or both.

You need some smart players with strong arms and quick reactions to pull this off. But if you can it can be a thing of beauty.

Plenty to Work On

These plays should give you some fun things to work on at practice. I wouldn’t start with them, but they can definitely help you change a game. And even if you never use them in a game they can inject a little extra fun into your practices.

Next week we’ll be looking at some offensive plays to help you generate more runs when you can’t just bash the ball. In the meantime, if you have any defensive plays you’d like to share leave them in the comments below.

The Kids Aren’t Alright. They’re Exhausted.

You see it all the time. Kids are at practice/lesson, or in a game, or in a tournament, etc. and they’re just not performing to the level at which they’re capable.

“C’mon Erin (or Lily or Leticia)!” parents or coaches yell. “Put some effort in. Quit dogging it and get your rear in gear.”

But the reality is Erin (or Lily or Leticia) may actually be giving all she has and more. Because the problem isn’t effort or intention. It could be fatigue.

According to a 2020 survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics and reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a little more than 10% of kids between the ages of 12 and 17 reported being tired every day or almost every day. Now, 10% doesn’t sound like a lot, but I’ll bet if you added in kids who report being tired at least some days during the week the number would go much higher.

What’s causing all this fatigue? One thing could be the crazy level of commitment that pretty much every activity (including fastpitch softball) demands throughout the year – and particularly through the school year.

In a lot of area, maybe most, kids have to wake up at 6:00 or 6:30 to get ready for school. They’re then there to say, roughly, 3:30. Once school is over they may have a school sport practice or game, one of which will happen every day during the week and often on Saturdays as well.

Once they’re done with school sports they rush to a team practice, sometimes in the same sport and sometimes in another. For example, they play volleyball at school and then head to softball practice, or strength and conditioning.

Now, if the other practice is happening once a week it has a minor impact. But a lot of teams these days practice 3-4 times a week IN THE OFFSEASON!

So now maybe that kid is being expected to go all-out physically and mentally for 4, 5, maybe even 6 hours with barely time to eat a little something for dinner.

By now it’s 8:00, 8:30, 9:00 or even later and the child who gave his/her all on the field and/or in practice still has to do a couple of hours of homework. Maybe more if there is a big project due or all the teachers loaded him/her up.

Then it’s brush your teeth and off to bed by 11:00 pm so you’re ready to start the cycle all over again.

Here’s where the problem comes in. Take a look at the chart below, which shows what time kids should be going to be based on the times they wake up for school.

Notice a discrepancy here? That 12 year old who wakes up at 6:30 am should be in bed by 8:45 pm, not 11:00 pm. When it happens night after night the sleep bank gets drained.

Ok, but surely kids older than 12 can operate on less sleep? True, but not as much as you might think.

The CDC recommends that kids 13-18 should get a minimum of 8-10 hours of sleep per night. Every night.

I’ll save you the trouble of doing the math. To get 8 hours of sleep, that teen who wakes up at 6:30 am for school should be going to bed no later than 10:30. If he/she needs a little more sleep to function well, bedtime should get pushed earlier.

But it’s not just the sleep that is causing the problem. It’s also the lack of downtime.

Running from school to practice/game to practice/lesson/conditioning to whatever else is going on day after day after day takes a toll.

Pretty soon there’s very little left in the tank. Performance suffers and the risk of injury increases.

Ok, that’s the problem. What’s the solution?

I don’t have a final, definitive answer. But I do have a few suggestions.

Cut back on offseason practices – This applies to every sport, not just fastpitch softball. I firmly believe in the value of being a multi-sport athlete. But teams don’t need to maintain an in-season practice schedule during the offseason.

In reality, the fastpitch softball season is either February until the end of July(ish) or June until the end of October, depending on when your state plays school ball. During that time practice all you want.

Outside of it, there is no real reason to go more than once a week. If players want more, have them do it on their own, where they can focus their efforts for a half hour instead of enduring a two-to-three hour team practice.

That schedule includes the fall ball “season.” If you’re in a state that plays high school softball in the spring, fall ball is offseason so treat it that way.

If you just feel you must practice more than once a week, keep practices shorter, focusing on the single thing you want to accomplish.

Parents, make some hard choices – I get that many kids want to do everything. But there is a cumulative effect in trying to do all of that, especially if everything is at a high level.

A better solution might be for your child to play one sport at a high level (such as A-level travel softball) and other sports, if they want them, at more of a recreational level where the schedule demands aren’t so high.

There will always be exceptions, or course. Some kids are capable of playing more than one sport at a high level. Most are not, however, at least not without suffering some sort of consequences.

Parents need to take off the parent goggles and really look at how their kids are doing. If they’re always tired maybe it’s time to take some things off of their plates so they also have time to rest and recover.

Take sleep needs seriously – Although I shared them, I think the sleep guidelines above are tough to manage. They’re also kind of generic, because some kids will need less – and some will need more.

But going to bed late and getting only five or six hours of sleep on a regular basis isn’t good for anyone. Parents, be sure your kids are getting the opportunity to sleep, even if that means opting out of practice on a heavy homework night.

As an aside, teachers may want to re-think the homework loads they’re assigning as well. The recommendation from the National Parent-Teacher Association and the National Education Association is 10 minutes per grade level, i.e., 10 minutes for first grade, 20 for second grade.

That’s total, not per-class. In addition, research indicates that more than two hours of homework total may be counterproductive.

Teachers should work together to keep homework focused and productive. Parents should work with teachers when they see excessive amounts of homework being assigned to ensure there is awareness of this fact and that a solution is created.

The bottom line is many kids are tired – physically, mentally, emotionally. They are over-scheduled and their time is micromanaged to a ridiculous degree, often as a result of adults seeking validation through the performance of those kids.

It’s unlikely this situation is going to improve on its own. It’s time to recognize the symptoms before they start getting more out of hand and taking steps to reduce the strain.

In the process, you’ll probably find those kids are closer to providing the performance level you desire.

Photo by Matheus Bertelli on Pexels.com

Rick and Sarah Pauly Pitching Clinic Coming to Northern Illinois Suburbs

Here’s some great news for everyone in the Midwest who has ever wanted to bring their daughters to a clinic with Rick and Sarah Pauly but were held back by the distance.

For the first time ever, Rick and Sarah are coming to the far north suburbs of Illinois – McHenry specifically! They will be at Pro Player on October 15 for two sessions.

The morning session will be more beginner/intermediate going over the basics of IR pitching. Great opportunity to try it out if you’ve never been exposed to it, or to get the core movements reinforced if you are already going down that path. Most likely that session will also cover the changeup.

The afternoon session is the advanced group covering movement pitches, including the rise and drop, along with the change. Pitchers in this group should already have strong fundamentals in internal rotation pitching, with the ability to throw hard with great control.

More information is available in the downloadable flyer below. This is a great opportunity for anyone to work with two of the best pitching coaches out there, but especially pitchers in Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa, and the UP. Take advantage of this opportunity while you can.

Why “I Don’t Know” Is Not a Sufficient Answer

If you asked the average person whether playing fastpitch softball is a physical or mental activity, there’s a good chance the answer would be “physical.” After all, there’s a lot of movement involved, and these days many softball players are training their bodies to the point of constant exhaustion (a topic for another day).

In reality, however, it’s a trick question. Because while it is obviously physical, there is also a huge element of mental activity that goes into it as well.

Or at least there should be.

When I train a player, I tend to use what’s known as the Socratic Method. The short version is I don’t just constantly tell them what to do; instead, once they’ve been taught something I will ask them questions to try to ensure they actually understand what we’re trying to do instead of just blindly following directions.

For example, if I am working with a pitcher and she throws a pitch in the dirt on her throwing hand side, rather than saying “You released too early” or “You were too open at release” or whatever the issue was, I will instead ask her “Why did that happen?” It is then up to her to think through what she has (supposedly) learned, plus what she felt, in order to provide an answer to the question.

The goal, of course, is to help the player become her own pitching, hitting, fielding, whatever, coach.

We want that so when she’s practicing on her own she can make corrections to keep her on the right path. We also want that because I’m sure the last thing that player wants is for Mom, Dad, Team Coach, or the spectators on the sidelines to be shouting instructions out to her in a game.

When I ask these questions the answers I receive aren’t always right. But to me there is one answer that is always wrong: I don’t know.

Because even if a player provides an incorrect response to the question, at least she’s making an effort to figure it out. She may not quite understand what she should be doing yet but she’s trying.

Saying I don’t know, however, to me shows a total lack of mental engagement in the process of whatever we’re doing. It’s the easy way out, basically saying, “Tell me so I can robotically follow directions” rather than really digging in to understand the movement we’re trying to achieve at a deeper level.

When I hear “I don’t know,” I always think of Mr. Hand and Spicoli.

In a softball context, in turning the tables the conversation would go, “Will I be able to get hitters out Coach?” “I don’t know.” “Will I get some hits instead of striking out?” “I don’t know.” “Will I be able to make the quick throw?” “I don’t know.”

And that’s the reality of it. If a player’s brain is not engaged as she practices she could just as easily be practicing the wrong things – in which case when she goes into a game she won’t have the skills she needs to succeed.

Now, I’m not saying “I don’t know” is always the wrong answer. If the coach who is asking the question of a player hasn’t taught her whatever he/she is asking, the player shouldn’t be expected to know. In which case “I don’t know” is correct.

Or if a player asks a coach about something out of his/her area of expertise, like how to throw a riseball if the coach has no background in pitching, or what strengthening exercises they should do at home if the coach hasn’t researched it, “I don’t know” is a better answer than just making something up so the coach doesn’t look “stupid.”

I actually wish more coaches would give that answer when it’s appropriate.

But when the activity is something fundamental that has been taught and reinforced dozens or hundreds of times before, “I don’t know” is not a sufficient answer. The player should know and be able to self-correct.

That’s the fast track to improvement and advancement. Because players who can identify issues on their own can correct them on their own and keep themselves moving forward; those who can’t, well, they’re doomed to repeat those mistakes over and over.

If you’re a coach, hold your players accountable by asking questions they should know the answers to and then making them accountable for it. If you’re a parent, reinforce the importance of players getting their brains engaged instead of mindlessly going through whatever motions they’re being told to do at the time.

And if you’re a player, take ownership of your softball education and really learn what you’re being taught. Not just the movements but the reasons for them, and why things go wrong when they go wrong.

It’s one of the biggest keys to producing better, more consistent results. Which makes the games a lot more fun.

Photo by Anna Shvets on Pexels.com

To Improve Pitching Mechanics Try Closing Your Eyes

One of the most important contributors to being successful in fastpitch softball pitching (and many other skills for that matter) is the ability to feel what your body is doing while it’s doing it.

The fancy word for that is “proprioception” – your ability to feel your body and the movement of your limbs in space. If you want to impress someone call it that. Otherwise you can just say body awareness.

Yet while it’s easy to say you should have body awareness, achieving it can be difficult for many pitchers, especially (but not limited to) younger ones. Keep in mind that it wasn’t all that long ago they were learning to walk, and many are still struggling to improve their fine motor skills.

Perhaps one of the biggest obstacles to achieving body awareness, however, is our eyes. How often do we tell pitchers to focus on the target, or yell at catchers to “give her a bigger target” when a pitcher is struggling.

According to research, 90% of what our brains process is visual information. That leaves very little processing power for our other senses.

It makes sense from a survival point of view. We can see threats long before we can hear them, or smell them, or taste them.

But if your goal is oriented toward athletic performance instead of survival, all that visual information can get in the way of feeling what your body is doing.

The solution is as simple as it is obvious: if you can’t feel your body when you’re practicing, close your eyes. (I do not recommend the same during a game since there is a person with a $500 bat at the other end of the pitch waiting to drill you with a comebacker.)

With your eyes closed, you no longer have the distraction(s) of what your eyes see. You HAVE to become more aware of what your body is doing, and where its various parts are going, if you’re going to have any chance of getting it even near the plate.

I have done this with many pitchers over the years, and it has invariably helped to different degrees. Some start to feel whether their arms are stiffening up or they’re pushing the ball through release where they couldn’t before.

Some feel their bodies going off line, or gyrating in all kinds of crazy directions instead of just moving forward and stabilizing at release.

In some cases, girls who were struggling with control actually start throwing more strikes with their eyes closed than they did with their eyes open. Again, because they’re starting to FEEL the things we were talking about.

One thing I like to emphasize with eyes-closed pitching is for the pitcher to visualize where the catcher is before she starts the pitch. See it in her mind’s eye the way she would see it if her eyes were open.

Then, once she has it visualized, go ahead and throw the pitch.

Even if she struggles at first she will usually start to feel what her body is doing at a much deeper level, putting her in a position to start correcting it. Then, by the time she opens her eyes again she will be better prepared to deliver the type of results you’re hoping for.

If you have a pitcher who is struggling to feel what she’s doing, give this a try. It can be an eye-opening experience for pitchers – and their parents.

Want to Get Better? Try Doing Nothing!

Ok yes, today’s title was purposely click baity. Because I don’t mean literally to sit around all day on the couch staring at a screen or eating Cheetohs (or doing both; I’m not here to judge).

Sorry all you players who hoped to use my blog to justify telling your parents to chill, or whatever you say nowadays.

What I’m actually talking about is learning to use your body the way it’s meant to be used rather than trying to do too much and getting in the way of your best performance.

A great example, and one I’ve talked about many times here, is using “hello elbow” (HE) mechanics for pitching.

With HE, you push the ball down the back side of the circle and try to get your hand behind the ball early going into the release zone. You then pull your arm through the release zone with your bicep while (supposedly) snapping your wrist hard as you let go of the ball, finishing with your elbow pointing at your catcher.

While this may seem like a way to add energy into the ball in theory, in practice the opposite is true. It actually slows down your arm, because your using the small bicep muscle instead of the larger back muscles to bring the arm down, and gets in the way of your arm’s natural movements as it passes your hip.

It’s also an unnatural movement pattern. To prove it, stand up, let your arms hang at your sides, and see which way your hand is facing. Unless you have something very odd going on your palm is in toward your thigh, not turned face-forward.

Your arm wants to turn in that way when you’re pitching too. In order for that to happen, all you have to do is NOTHING – don’t force it out, don’t force a follow through, really don’t do anything. The ball will come out as your hand turns and you will transfer way more energy into the ball than you would have if your tried to do something.

This, incidentally, is something I often use to help pitchers whose arms are naturally trying to do internal rotation (IR) but are also using an HE finish because that’s what has been drilled into them for the last three years gain a quick speed boost. They start out using their HE mechanics from the K position and we look at the speed reading.

I then have them lose the forced finish and just let the arm naturally pronate at it reaches the bottom of the circle. They can usually add 2-3 mph immediately just by doing nothing.

Or let’s look at hitting. Many young and inexperienced hitters will try to over-use their arms and shoulders when bringing the bat to the ball.

It makes sense on some level because the bat is in your hands and you want to hit the ball hard.

Yet that is the one of the worst things you can do. When you pull the bat with your arms and shoulders you have to start your swing before you know where the ball is going to be (never a good idea).

You will also lose your ability to adjust your swing to where the ball is going because you’ve built up so much momentum in whatever direction your started. Not to mention that muscles get smaller and weaker as you move away from your core so you’re not generating nearly as much energy as your body is capable of producing.

Again, the better choice is to do nothing with your arms early in the swing, and instead let your lower body and core muscles generate energy and start moving the bat toward the ball (while the bat is still near your shoulder). Then, once you’re well into your turn and you see where the ball is headed you can let the bat head launch, resulting in a much better hit, and a more reliable process.

Does doing nothing work for overhand throwing as well?

How many times have you seen players lined up across from each other, throwing arm elbow in their glove and wrists snapping furiously while their forearms don’t move? Probably more times than you can count.

This is a completely pointless drill because no one, and I mean NO ONE, purposely snaps their wrists when they throw overhand. Instead, they relax their wrists and allow the whipping action to snap their wrists for them – which is far more powerful.

To prove it, close your fingers up and try to fan yourself by snapping your wrist. Not much air there, right?

Now relax your wrist and move your forearm back and forth quickly. Ahh, that’s the stuff. That breeze you now feel is more energy being generated, which moves more air into your face.

So if that’s the case, why would you ever try to do something when you’re releasing the ball rather than doing nothing and letting biomechanics produce better results for you?

There are countless other examples but you get the picture. The point is, forcing unnatural movements onto your body, while they might make you “feel” like you’re working harder, are actually very inefficient.

If you want to maximize your performance, make sure the energy you’re producing is delivering the results you’re going for. Just doing nothing and watch your numbers climb.

Photo by Oleksandr Pidvalnyi on Pexels.com