Be Brave Enough to Try New Things…And Abandon Them

One of my favorite coaching-related sayings, which I first saw in the signature of a member of the Discuss Fastpitch Forum and which is often attributed to Henry Ford, is, “If you do what you always did, you get what you always got.” In other words, you’ll never get beyond where you are now if you’re not willing to make changes.

Really, making changes is the essence of what we do in coaching. We see something that doesn’t quite look right, or we want to help a player perform beyond the level they’re currently at (such as a pitcher gaining speed) and we have them do something different.

Some coaches, though, might be afraid to suggest those kind of changes – and some players might be afraid to try them – because they’re worried they might have a negative effect. And they’re right – they might.

Here’s the thing, though. Look at the words I just used: “suggest;” “try.”

You’re not committing to permanent changes, just doing something temporary to see what effect it has. As you would in any good science experiment.

If you’re a coach and you see an idea from a credible source and think it might help your player or student, you can make the suggestion that she tries it. Just be sure you know why you’re doing it.

There is a lot of garbage out on Instagram and other social media masquerading as good ideas. Usually it’s from people who are less coaches and more content creators.

They depend on crazy stuff that looks good in a video but doesn’t necessarily have any value in developing fastpitch softball players to help them gain more clicks and likes and shares. I get it, that’s how they make money, but the drills themselves are often just giant wastes of time that could be better-spent developing real fundamentals.

But let’s say you’ve seen or heard a new idea that makes sense to you, and you think you know who in your orbit might benefit from it. Still, you’re also afraid it might not work, or even screw them up.

Go ahead and suggest it anyway. Have your student(s) or player(s) try it and see what happens. Maybe it works, maybe it doesn’t.

Maybe it’s a godsend, or maybe it’s a disaster. Or maybe it’s both, depending on the student or player.

The thing is, if it helps you can keep it. If it doesn’t, it’s ok to say, “Never mind, go back to what you were doing before.”

Again, remember in this case you’re not trying to solve a known problem, such as a hitter swinging all arms. Whether she likes it or not that’s something that needs to be corrected in order to perform well.

Instead, you’re trying to help a player build on a strong foundation to enhance her level of success – such as helping a hitter who has decent fundamentals but is making weak contact hit the ball harder.

Again, like any good science experiment you want to introduce a single change and see what happens. If it works, great; if it doesn’t, you can get rid of it.

Either way, you have now learned something valuable that will help that player in the future.

I think coaches, especially newer coaches, are often afraid to admit they were wrong about something because they think it makes them look weak or stupid. Actually, the reverse is true.

The best coaches I know are constantly trying things to see if they help. They understand that what works for one person may not work for another, so they test different ideas to find which ones do work.

They’re also not afraid to change their long-held beliefs if they find an idea or a technique that works better. They know that closed minds are like closed bowels – not good for anyone.

As David Genest at Motor Preference Experts often says, there are 8 billion people in the world, which means there are 8 billion movement profiles. The key to success if figuring out which major changes or even minor tweaks fit the profile in front of you rather than a pre-conceived notion of what a pitcher or hitter or catcher or fielder should look like.

When I make a suggestion like this, I will usually say, “Let’s try this and see what happens.” After a few repetitions if performance goes up I’ll say, “Good, let’s keep working on that.”

If it goes down, I will say, “Well, that didn’t help” or words to that effect and we’ll usually go back to what we were doing before. No sense beating a dead horse.

When you’re doing these little science experiments, always be sure to include the student or player in the process. Ask her how that felt and encourage her to be honest.

You’re not looking for ego reinforcement; you’re looking for feedback to help determine if that change is worth keeping. Do keep in mind that sometimes a change will cause a performance loss just because it’s different and the student or player isn’t able to do it with full effort.

But if you’re observing carefully, you should be able to tell the difference between something that’s a little odd and something that just flat-out doesn’t work for that student or player.

Trying something new can be a little uncomfortable or even a little intimidating. As a coach you want to subscribe to the concept of “First do no harm.”

A little trial and error, however, is healthy as long as you remember you can always walk it back if the experiment shows that’s NOT the way to do it. And you’ll be that much smarter for the effort.

Before You Go Ballistic Over Errors or Other Mistakes…

When I sat down to start this week’s blog post I found myself staring at a blank screen, wondering what I should write about. Then serendipity struck in the form of my good friend Tim Boivin.

Tim just happened to send me a link to this Facebook post from United Baseball Parents of America showing Phillies teammates consoling Orion Kerkering after his misplay of a comebacker in the 11th inning put the final nail in the Phillies’ exit from Major League Baseball’s postseason. You can read more about that play here.

First of all, as I’ve said many times, one bad play or one bad call is never THE reason for a loss. If the Phillies had scored a few more runs earlier in the game, or prevented the Dodgers from scoring its only other run, that 11th inning misplay never would have happened and the Phillies would have one.

That point aside, though, making an error that ends a game can be devastating for any ballplayer in any game, but even moreso when it’s not just game-ending but season-ending. If you see any of the post-game photos or interviews the heartbreak is obvious.

Not to mention all the fan chatter that’s no doubt going to haunt him for a while – all the keyboard warriors and barstool experts who never made it past 12U rec ball who are going to talk about how “bad” he is and how he should be drawn and quartered for costing “them” the series. But at least he has the consolation of an MLB paycheck, which will help him get through it pretty handily.

Now think about that in terms of your youth, high school, or even college player. If one of the most talented athletes in the world – and if you’re playing MLB you are no matter where you fall on that scale – can have a momentary glitch in a big game, why would you think your young player would be immune from it?

And think about the fact that there was a lot more at stake for the Phillies coaches and other players than there is in your typical weekend tournament. Yet the coaches didn’t scream at Kerkering and the other players came over to console him when he was down.

That’s an object lesson we should all keep in mind. No one sets out to misplay a ground or fly ball, or give up a fat pitch down the middle, or strike out, or throw to the wrong base. That stuff just happens – unfortunately it’s part of the game.

We do have a choice, however, on how we react to it. Any player with any sense of game awareness realizes when she (or he) has made a critical, game-changing mistake and most likely feels bad about it.

Rather than going ballistic, the better reaction is help that player understand that this momentary lapse will not define him/her for life. Despite what it may feel like right now, it’s just one more bump on a road that will be filled with them.

Emotional scars can run deep, and the body keeps the score for a lot longer than most of us realize. By helping players keep these glitches in perspective you can save them a lot of heartache now and in the future – and reduce the chances of a repeat performance should those players find themselves in another high-pressure situation again.

Also remember that at the end of the day it’s just a game. No one was seriously damaged when Kerkering muffed the play, and no one will be seriously hurt when a 12 year old softball player makes a mistake either.

Keep it in perspective and the fastpitch softball experience will be a lot better for everyone.

Why It’s Important to Celebrate Progress, Not Just Achievement

Everyone loves to celebrate the big achievements in softball – winning a tournament or conference championship, tossing a no-hitter, hitting the game-winning home run, and so on. Those are definitely highlight in a player’s career and should be lauded whenever they occur.

Yet celebrations of a player’s performance don’t always have to wait for some major achievement. In fact in my experience it’s often more important to celebrate progress, even if it’s on a small scale, because those little wins now are usually what lead to those big wins down the road.

Here’s a good example. Let’s say you have a hitter who, as they say in Bull Durham, couldn’t hit water if she fell out of a boat. She’s all arms with no control over the bat, and she seems to defy the law of averages by not even making random contact through sheer luck.

Realizing it’s a problem she starts to take hitting lessons, and within a couple of lessons she hits a weak ground ball to second and pops out to first in the same game. Nothing to write home about in the big scheme of things – it’s still a couple of outs – but she at least put the bat on the ball.

That’s something to celebrate because it represents progress. Now, perhaps inspired, she keeps working at it and next game hits a hard line drive to shortstop or flies out with a direct hit to the left fielder.

Again, she is showing progress. Because you are celebrating and encouraging her she continues to work, and suddenly those hard-hit balls start finding some gaps between fielders.

It’s been little steps along the way, but they have been important steps. And maybe before you know it she’ll come to bat with the game on the line and produce one of those highlight reel moments that would have been unthinkable not too long ago.

I’ve seen it happen. If you have, tell your story down in the comments.

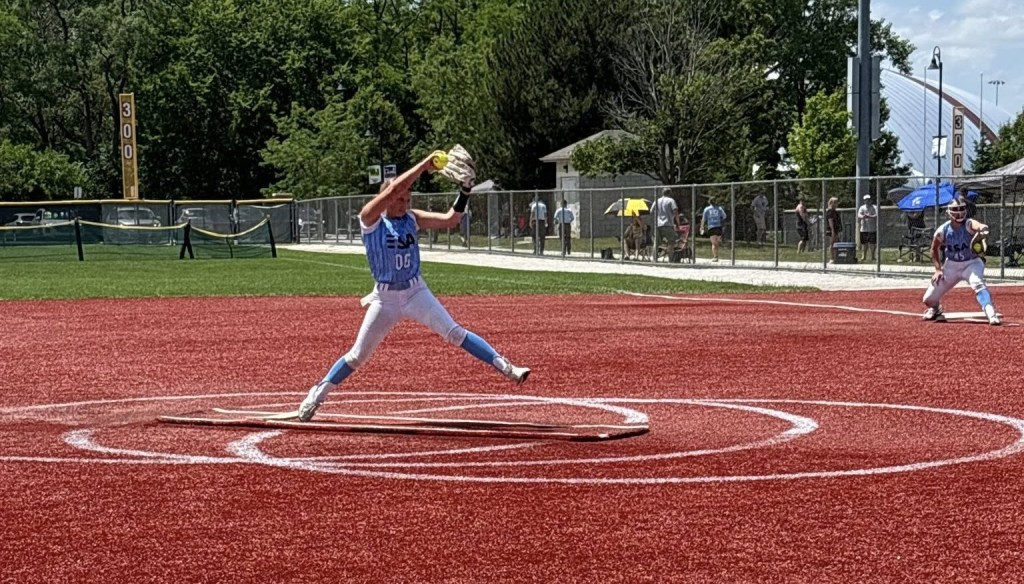

Or what about the pitcher who can’t seem to find the plate with both hands and a flashlight due to poor mechanics? She can force the ball over enough to keep giving her opportunities, but her walks are still out-pacing her strikeouts and soft contacts and you’re starting to reconsider your position with the playoffs coming.

She realizes it too and starts taking the need to work on her mechanics more seriously. She puts in the work and you can see her start looking more like a pitcher should look, even if the outcomes, while better, still aren’t where the team needs her to be.

The same goes for pitchers and speed. It takes some longer to figure things out than others, or for their bodies to even have the physical capacity to deliver an appropriate level of speed for her age.

But if she keeps working on the mechanics and on learning to feel what her body is doing at different points in the pitching motion, the improvement will come.

Again, by celebrating the progress you can send a message that what she’s doing is working and she should keep on doing it. That little bit of encouragement may be just what she needs to fulfill her potential and become a reliable member of your pitching rotation.

These are just two examples of what is often called the “grind.” While it would be wonderful if you could just make a tweak here or there and see it pay off instantly, that’s not how it usually works.

Progress doesn’t come in leaps and bounds for most; it’s normally a lot more incremental. But if you wait to recognize only the big achievements they may never happen because the player gets discouraged before she reaches that point.

A better approach is to look for the good, even when it’s small, and call it out to keep players going when the going gets tough.

Now, all of that assumes these players are working on making the changes that are needed in order for progress to occur. Empty praise doesn’t help; they have to be making the effort to fix whatever is preventing them from getting better or they’re just going to fall further behind.

But if they are, take the time to recognize the progress even if the big achievement doesn’t come right away. Because it will in time.

Buying Tools v Learning to Use Them

Like many guys, at one time in my life I thought woodworking would be a great, fun hobby to learn. Clearly that was before my kids started playing sports.

So I started becoming a regular at Sears, Ace Hardware, Home Depot, Menards, Lowes, and other stores that sold woodworking tools. YouTube wasn’t a thing back then (yes, I am THAT old), so I also bought books and magazines that explained how to do various projects.

Here’s the thing, though. I might skim through the books or an article in a magazine to give me just enough knowledge of which end of the tool to hold, then I’d jump right in and start doing the project.

Needless to say, the projects I did never quite came out the way the ones in the pictures did. I also didn’t progress much beyond simple decorative shelves and things like that – although the ones I did make held up for a long time.

The thing I discovered was that buying new tools was a lot easier, and a lot more fun, than learning how to use them. Buying tools is essentially “retail therapy” for people who aren’t into clothes or shoes. And you always think if you just had this tool, or this router bit, or this fancy electronic level, everything will come out better.

Nope. Because no matter how good the tool or accessory is, it still requires some level of skill to use it.

Fastpitch softball parents and players often suffer from the same affliction. They believe that if they get the latest version of expensive bat they will hit better.

They believe if they purchase this gadget they saw promoted on social media it will automatically cure their poor throwing mechanics. They believe if they purchase this heavily advertised pair of cleats they will automatically run faster and cut sharper.

Again, nope. New softball tools like bats and balls with parachutes attached and arm restricting devices and high-end cleats are certainly fun to buy, and there’s nothing like the anticipation and thrill of seeing that Amazon or FedEx or UPS truck coming down the street to make you want to burst into song.

But they’re just tools. In order to get the benefits of those tools you have to learn how to use them correctly then work with them day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year.

And as we all know, that part isn’t as much fun. There’s a reason it’s called the grind.

Take that bright, shiny $500 bat. If you’re still using a $5 swing, or you’re too timid to even take it off your shoulder, it’s not going to do you much good. It may look pretty but you could be using a $50 bat to the same effect.

You have to get out and practice with it. Not just during practice but even when no one is around. The more you do it the better you’ll get at learning how to use it – just like I discovered with my fancy jigsaw.

Pitching, fielding, throwing, baserunning, it’s all the same. No fancy glove or high tech gadget is going to help you get better no matter how much it costs. You have to learn how to use it, which means getting off your butt (or off your screen) and using it.

If you don’t know how to use it, seek out somebody who does and have them help you. It’s a pretty good way to shortcut the learning process, and often a better way to invest your time and money.

Yup, sure, new tools and toys are a lot of fun to wish for and shop for and buy. But even the best ones can quickly become shelfware if you’re expecting them to do all the work for you.

Get the tools that will help you get the job done, but always remember you have to learn how to use them to reap the full rewards. Otherwise you’re just throwing away money.

Help for Pitchers Who Are Banging Their Elbows Into Their Hips

It’s more common than you might think: pitchers, especially those who are trying to keep their pitching arms in close to their bodies (as they should) suddenly start feeling slight to intense pain as they go into release. Once it catches their attention, they realize their elbows are hitting their hips. HARD.

Well-meaning coaches, other pitcher parents, and even some random people will tell them to solve the issue they should clear their hip out of the way or bend out more so their arm totally misses their body as they go into release. While yes, that will solve the immediate issue, it will also create less-than-ideal mechanics that will ultimately limit most pitchers’ ability to compete at a high level.

That’s because compression of the upper arm against the ribcage and light brush contact of the forearm are both essential to stabilizing the shoulder complex to prevent a more serious injury, transfer more energy into the ball to improve speed, and sure consistency of release to improve pitch accuracy/command.

By now you may be asking if that’s the case, why is my pitcher/daughter getting giant bruises on her elbow area and/or hip area while other pitchers are not? The simple answer is because those who are not raising those ugly bruises are making contact differently than those who are.

The bruises are coming from the position the arm and hip are in going into release.

When the bruises are happening, the elbow are is making direct contact with the pelvis (hip bone), crashing into it in a bone-on-bone manner. When they’re not happening, the pitcher is making contact with with the soft tissue (muscle) on the forearm just below the elbow into the muscle (soft tissue) on the side of the hip, interrupting the acceleration of the arm enough to transfer the energy without stopping it completely.

So what causes the elbow to slam into the hip instead of passing by it? I find that typically there are two causes, which can happen either independently or in the worst cases at the same time. Correct those and the problem usually goes away,

Cause #1: Staying Too Open

Every pitcher needs to open her shoulders and hips (externally rotate) to some extent to create an aligned, powerful arm circle. The shoulder in particular is important because when you are facing straight ahead, the arm can only come back so far before it has to deviate off-line.

This deviation stresses the shoulder, leading to injury, and takes the arm out of its ideal movement around the shoulder, affecting both speed and accuracy. Opening the shoulders makes in possible for the arm to move around at incredible speed while using the shoulder the way it’s designed to be used.

The problem occurs when the hips and shoulders don’t come back forward to an area around 35-50 degrees going into delivery. The body then starts blocking the arm, and the pitcher either has to then go around it or slam her elbow into her hip.

Think about where your elbow is when you are just standing normally. It sits squarely on your hips. If it does that while you’re standing still, what makes you think it won’t do that when you’re aggressively trying to throw a pitch.

The cure for this is to move into that 35-50 degree angled range we mentioned earlier. When you are in this position, even standing, your elbow is clear of your hip while allowing your forearm to still make light brush contact with the side of your hip as it passes the hip.

To learn that, have the pitcher do a ton of easy walk-ins, where she starts out facing the plate, then takes an easy step with her throwing-side foot before going into the pitching motion. She should do this slowly, with no leg drive at all, and focus on moving her body open with good external rotation of the shoulders and then back into a roughly 45 degree position.

On the field you can throw a regular ball from a short distance. But at home, have her look into a mirror as she does the movements without a ball, paying attention to how her body is moving and coming back to the finish position.

Ideally, her hips will move a little ahead of her shoulders as she comes down the back side. Once she can do it without a ball, have her throw a rolled up pair of socks or a lightweight foam ball into the mirror, again paying attention to how her body is moving.

You get all the benefits of brush contact while maintaining solid posture (no contorting to move the hips out of the way or throw the shoulders too far off) so the pitcher can pitch pain-free.

Cause #2: Keeping an Arch in Your Back

The second major cause of banging the elbow into the hip in a way that causes injury is having your back arched backwards going into release. This can happen even if you are getting to the 35-50 degree position we talked about above.

At the top of the circle, it is desirable for a pitcher to have her back arched back at least 15 degrees toward first if the pitcher is right-handed or toward third if the pitcher is left-handed. It’s a movement that helps load the muscles in the back so they can help accelerate the arm on the way down. It also helps getting proper external rotation and keeping the arm on-path.

After the peak of the circle, however, the arch should come out and the pitcher should be in some level of flexion by the time she is going into release. In other words, she will be slightly bent toward third if right-handed or toward first if left-handed.

If the arch doesn’t come out, however, it pulls the pitching elbow backwards instead of letting it flow freely through its natural path. When that occurs the pitcher will either bang her elbow into the side or even back of her hip.

She may also try to compensate for this bad position by trying to move her elbow away from that area, causing her to throw low and very inside, which will make pitching even more difficult than it already is.

To solve this issue, the pitcher needs to learn how to come out of the arch as her arm comes down the circle. One way to do that is to have her practice throwing a pair of rolled up socks into a mirror, watching herself to see what position her body is in when overhead and then when releasing the socks.

She should see herself arching at the top then flexing in at the bottom. You can even put a piece of tape on the mirror to help her see it. Have her start slowly, then build her speed until she can execute it without thinking.

Another way to address this issue is a drill I got from Rick Pauly of PaulyGirl Fastpitch called the Bow-Flex-Bow. For this one you will need a piece of Theraband that is at least as long as the pitcher’s arm.

Have her grab both ends of the Theraband and stand at a 45 degree angle, as if getting ready to do a pitching drill. She then takes the Therabad up and into a pitching motion, with both hands moving forward toward the “plate” before starting to separate overhead.

When she is at the top of the circle her back will need to arch to get the Theraband behind her head. As she comes down, make sure she bows back in to come to the finish so instead of arching/flexing back she is now flexing forward.

Baby and Bathwater

No question that banging your elbow into your hip is not only unpleasant but counter-productive for achieving both speed and accuracy. But totally avoiding any contact between the body and the arm isn’t the way to go either.

The issues listed here aren’t the only reason it can happen but they are the two most common. By making the corrections to achieve proper upper arm compression and light brush contact you can stop the pain while improving performance.

Fastpitch Players: Adopt the Confidence of a Cat

Anyone who has a cat, or who hangs out at the home of someone who has a cat, knows this scenario: The cat is walking along a precarious path, such as the back of a couch or a very thing shelf. Suddenly, the cat loses its footing and lands on the next surface below.

No matter how ridiculous the cat looked when it was falling, or how awkwardly it landed, it will always have the same reaction: it will get up (if it didn’t land on its feet as they usually do), straighten itself out, and look around the room with an expression that says, “I meant to do that.”

Fastpitch softball players can learn a lot from that reaction. All too often, when a player makes a mistake (such as a pitcher sailing a pitch into the backstop or a hitter swinging at a pitch that, um, went sailing into the backstop), the player will react as though she just accidentally published her most private thoughts on her Instagram account.

Once she’s had that reaction it gets into her head. Sometimes it affects the next few pitches or plays; sometimes it affects the rest of the game, the day, or the weekend.

This doesn’t just happen at the youth levels either. College players can suffer from this debilitating reaction as well.

Once it starts it’s hard to stop. And it can also have a ripple effect, especially if it’s a pitcher who does it. The rest of the team usually takes its cue from the pitcher, so if the pitcher is freaking out you can bet that at some level the rest of the team is freaking out as well.

So what to do about it? You have to train it, like anything else.

Because while cats react with a superior air instinctively; athletes generally do not.

Coaches and parents can help their athletes overcome those tendencies by not overreacting themselves. Remember that no one sails a pitch or bobbles a grounder or drops a popup or swings at a bad pitch on purpose.

It just happens. Staying positive in the moment, or at least not going nuclear, can help players move past a mistake faster so one issue doesn’t turn into multiple issues.

Ultimately, though, it’s up to the players themselves to take on this attitude. While it may come naturally to some, most will probably worry too much about letting down their team, their coaches, their parents, as well as looking bad generally.

They have to learn that errors or other miscues happen to everyone, and have to have the confidence to keep going even when they want to shrink or crawl into a hole.

In my opinion this attitude is particularly important for pitchers, because the rest of the team often takes its emotional cues from the girl in the circle. If she gets frustrated, or upset, or off her game in any way, it’s very likely she’ll take most if not all of the team down with her.

Which means the team behind her will under-perform just when she needs them to be better to pick her up.

Anyone in a captain’s or other leadership role also must take on that cat-like attitude. Remember that the characteristic that makes you a leader is that people will follow you. So you have to decide where you want to lead your followers – into a deeper hole or beyond any problems.

Taking on an “I meant to do that” attitude, even when everyone knows they didn’t, will give everyone else the confidence that everything is fine so they can play without fear of failure. Isn’t that the definition of what leaders do?

For those who don’t have access to a cat themselves, the Internet is filled with cat videos that demonstrate this behavior. Check some out and see how they react to the biggest miscues.

Then have your favorite players adopt that attitude for themselves. You’ll be amazed at the difference it makes.

Fall Ball Is a Great Time to See What You Have

It seems like only yesterday that the summer travel ball season was getting started – and teams were already promoting open workouts and private tryouts for the next season.

Well, next season is now officially upon us, and with that comes fall ball games. Back when I was coaching teams, fall ball usually meant one practice a week, a couple of double headers (if you could find another team that wanted to play), and maybe a tournament or two if you could scrape up enough players who weren’t committed to fall sports at their schools.

Nowadays for most teams, though, practices are multiple times per week (3-4 for some teams!), there’s a tournament practically every weekend through Halloween, and maybe even a few more “friendlies” sprinkled in here and there. That’s progress I guess.

If you are following this type of heavy schedule I do have a suggestion for you: don’t just treat it like summer ball 2.0. Instead, use at least some of this time to figure out what you have in the way of players. I mean, hopefully you chose well in the tryout process, but you never really know until you see them in action.

To do that effectively you have to be willing to do something that many coaches these days seem reluctant to do: potentially lose some games you might have otherwise won.

For example, instead of pitching your Ace for one out of two games of pool play and as many bracket games as she can go without her arm falling off like you usually do, try using your #2, #3, or even #4 more. Your #1 will probably appreciate the additional rest and recovery time, and you’ll have more opportunity to see what the other pitchers (especially the new ones) can do in a game situation.

There is also an added bonus to this strategy: If your #1 is a strikeout pitcher and the others are more “pitch to contact,” your fielders will get more work and you’ll gain a better understanding of exactly what you need to work on – whether it’s skills, knowing what to do with the ball, communicating effectively or some other aspect. Better to find out now than next summer when it’s probably too late to do anything about it.

One other thing you can do with pitchers is maybe leave them in the circle a little longer than you usually might to see if they can work their way out of a jam or regain their control if they start to lose it a little. Sometimes all a pitcher needs to get out of funk is to get more innings; this is the perfect time to make that happen.

You can also use the fall to shake up your batting order a bit and give hitters who normally are at the bottom a chance to get a few more at-bats. Maybe you don’t move the whole bottom up to the top at once – no sense in going crazy with it – but moving one or two up strategically might help them find their rhythm better and might give you some extra quality bats throughout the lineup for when you need them most.

Going back to fielders, the fall gives you a good chance to see what your backups at a particular position can do. Instead of using, say, the same shortstop or the same catcher, or the same something else in every game, put those backups into a starting role and see how they handle it; they might just surprise you.

The fall is also a good time to try out different strategies to A) see how your team handles them and B) short up any areas of deficiency you discover.

For example, I know the short game isn’t as important in fastpitch softball as it used to be. Everyone digs the long ball these days, but there are still times when the ability to perform a suicide squeeze or lay down some other type of bunt can make the difference between winning and losing a big game.

If you try it in the fall and it works, you’ll have more confidence trying it next spring. And if it doesn’t, well, that practice plan kind of writes itself.

The same goes for unusual defensive sets. If you’re facing a speedy slapper maybe you want to try pulling your second baseman or shortstop in closer, like up next to the circle, to see if you can take away her speed.

Or if you’re facing a situation where you’re pretty sure the offense is going to try a bunt, bring your first and third basemen in about 15 feet away from home to give them a better shot at making the play. You can even try having them shift into that from a more traditional set once the pitcher is ready to throw the pitch so you don’t give it away.

You can also use the fall to try some trick plays, like those first and third plays you keep practicing but never call, or faking a throw to first on a ground ball to see if you can sucker the lead runner into a rundown. The possibilities are endless.

Sure, there are times when you’re going to have to go with what you know. If you’re trying to win an early bid to Nationals next year to get that out of the way you’re probably going to want to play to win. But if it’s a meaningless tournament, or a showcase where you’re just going to play X number of games and then go home, why not use it to find out what you don’t know?

Yes, it can be difficult to lose a game you might’ve won, and nobody likes losing. But taking that small risk now can pay big rewards down the road.

Don’t just take it from me, though. On our From the Coach’s Mouth podcast Jay Bolden and I have spoken to several college coaches who have followed this fall ball strategy to help them get ready for the spring. If it’s good enough for them…

Leaves photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

A Softball Lesson from General George S. Patton

When I was still working in the business world, I used to have this quote from WWII General George S. Patton hanging in every cubicle and office I worked in:

“A good plan, violently executed today, is better than a perfect plan executed next week.”

I would also copy the paper I had it on and give it to new co-workers when they joined the company, especially the younger people who might be intimidated coming into their first big jobs.

I found them to be great words to live by for a variety of settings. And they definitely work for fastpitch softball.

Think about hitters. We’ve all seen hitters who let good pitches go by waiting to see the perfect pitch.

They wind up in an 0-2 hole, where their odds of seeing a perfect pitch go down substantially, and as a result their chances of getting a good hit drop significantly as well.

Or take pitchers who are working on a new pitch. They feel like they’re doing pretty well with it, but they (or their coaches) are reluctant to use it in a game because they don’t have full (perfect) control over it yet.

The result is they never gain game experience with it because none of us is ever going to be perfect. Instead of waiting for absolute reliability, I say pick a safe situation (nobody on, nobody out, 0-1 count for example) and give it a try.

Worst case the count goes to 1-1, but it could have done that anyway with a “safer pitch” that the pitcher doesn’t throw well or that the umpire misses. Throw that new pitch so you start getting used to it in game situations so you have it for later – not to mention maybe it works the way it should now even if it’s by luck and you start building confidence.

The words of General Patton don’t just apply to players either. Coaches, how many times do you work on a defensive play for when there are runners on first and third, or a special offensive play such as a suicide squeeze, only to be too afraid to try it in an actual game?

Your team’s ability to win an important game might just come down to its ability to execute one of these high-risk plays. But if you’re too worried it’s not ready when you’re playing a friendly or a non-conference game, you’ll never know if it’s ready when it counts.

I say give it a try now, when a screw-up doesn’t mean as much, and see what happens. Maybe you learn your team is close to executing it but needs a little more work; maybe you learn there’s no point in wasting valuable practice time because your team is never going to be ready to pull it off with any degree of certainty.

But at least you’ll know.

Remember that in softball, as in most things in life, the situation is changing constantly. Waiting until you have the “perfect” conditions or opportunity means you could be passing up a whole lot of other ones that, while they carry a little more risk, also carry a lot of potential rewards.

With fall ball coming up, this is the perfect time to trot out some of those special plays, or new pitches, or more aggressive approaches at the plate, or new fielding techniques, whatever else has been gathering dust in your back pocket.

Prepare as best you can in the time you have, then give it a try. You may just surprise yourself.