Blog Archives

What It Takes to Really Learn Something (or Unlearn Something)

When I was but a lad heading into high school, my heart’s greatest desire was to learn how to play the guitar. Partially because I loved music, but also because I thought doing so would help me meet girls.

(Don’t judge, Eddie van Halen started on guitar for the same reason, although he did a little better than me on learning it.)

Anyway, for my 14th birthday (just as the summer started) my parents bought me the cheapest piece of junk available that will still work, a $20 Decca guitar from Kmart. But I didn’t care – I had a guitar, along with a little songbook with songs like Born Free and Red River Valley that had the little finger placement charts above every chord.

I pretty much spent the entire summer locked in my room for 4-6 hours a day every day, playing the same old songs over and over until they began to sound like actual songs. In a month I felt comfortable enough to play that guitar in front of my parents and a couple of their friends.

Within a couple of months of starting I bought my first “real” guitar for $100 out of my 8th grade graduation money – a Suzuki 12 string that I still own to this day. It’s not very playable anymore but I still keep it around for sentimental reasons.

I tell you this story to point out a valuable lesson: if you really want to get good at something, you can’t just dabble at it or put in time against a clock. You have to work at it deliberately, with a goal and a sense of purpose.

In other words, you have to know your “why” or you’re just going to spin your wheels.

So if you’re a pitcher who is trying to increase her speed or learn a new pitch, you can’t just go through the motions doing what you always did. You can’t just set a timer and stop when the timer goes off.

You have to dig in there and keep working at it until you make the changes you need to make to reach your goal.

If you’re trying to convert from hello elbow to internal rotation, you can’t just throw pitches from full distance and hope it’s going to happen. You have to get in close, maybe slow yourself down for a bit, and work on things like upper arm compression and especially forearm pronation until you can do them without being aware of them.

It might take a few hours or it might take a month of focused, deliberate practice. But you have to be willing to do whatever it takes to get there.

The same goes for hitters. If you’re dropping your hands as you swing or using your arms instead of your body to initiate the swing you’re not going to change that overnight by wishing for it.

You have to get in there and work at it, and keep working at it until you can execute that part of hitting correctly. No excuses, no compromises; if you want to hit like a champion you have to work like a champion.

There will sometimes be barriers that seem insurmountable, and no doubt you’ll get frustrated. But there is some little thing holding you back and you attack it with ferocity, with a mindset you won’t let it defeat you, sooner or later you will get it and be able to move on to the next piece.

When I first learned how to play an “F” chord it was really difficult. It requires you to use your fingers in ways other chords don’t, especially when you’re a beginner.

But I needed to master that “F” chord cleanly so I could play certain songs, so as physically painful as it was (especially on that cheap little Decca guitar) I kept at it for hours on end until it was just another chord among many in the song.

The same will happen for you if you work at it. The thing you can’t do today will become easy and natural, and that will put you in a better position to achieve your larger goals.

Yes, it takes a lot to make a change, especially if it’s from something you’ve been doing for a long time. Old habits die hard as they say.

But if you approach it with passion and purpose you’ll get there – and you’ll be better-positioned for your next challenge. .

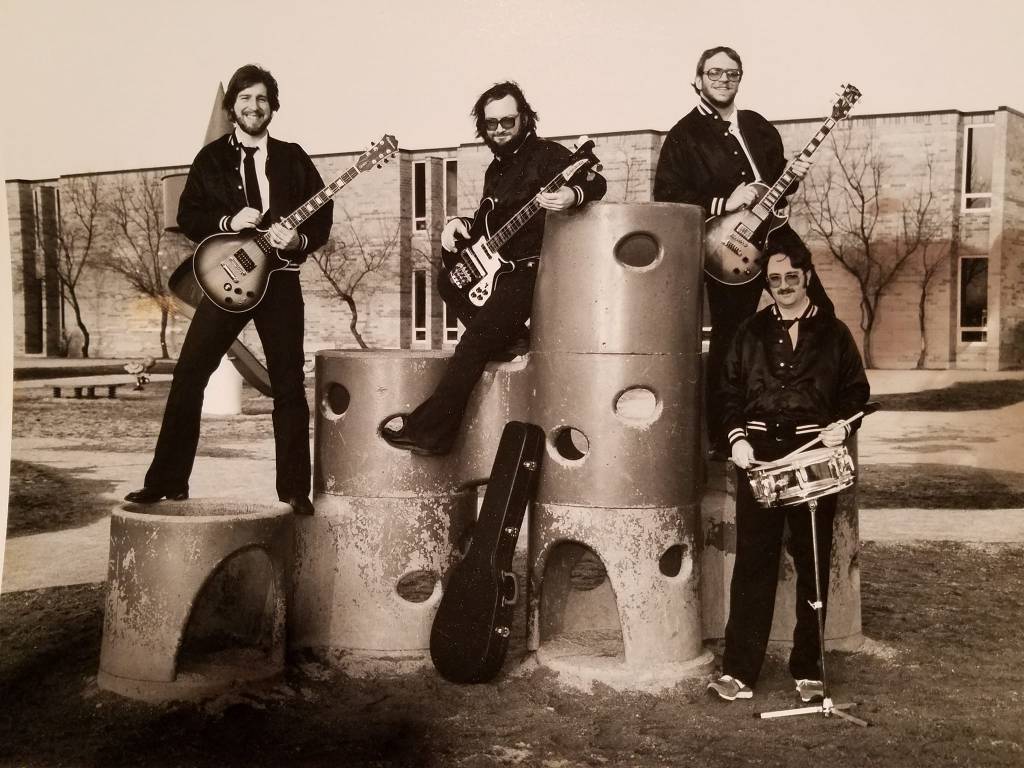

BONUS CHALLENGE: Yes, one of those young fellows up there in the top photo is me. See if you can guess which one and put your choice in the comments below. (HINT: It may not be the one you think.)

Lessons from the Great Wall of China

Pretty much everyone knows or at least has heard about the Great Wall of China. It’s quite the construction feat, running 13,170 miles using materials such as earth, stone, and brick.

While we think of it as one cohesive structure, it’s actually a series of fortifications built by multiple dynasties. While there are no receipts from Lowe’s to tell us exactly how many bricks were used to build it, researchers have estimated it took anywhere from 3.8 to 42 billion bricks/stones to create the incredible wall we marvel at today.

Now think about this: The Great Wall of China wasn’t just plopped in place whole. Each of those 3.8 to 42 billion bricks was laid in place, one at a time, over a period of 2,000 years. All without the help of any modern powered equipment – just hard, backbreaking manual labor from slaves, convicts, soldiers, and random peasants who couldn’t run away fast enough.

And before they could lay the top parts that people walk along and ooh and aah over, they first had to put the ones along the ground in place. And then the layer above that, and the layer above that, and so on.

The same is true for building skills in fastpitch softball (or anything else for that matter, but hey, we’re talkin’ softball here). All too often I see posts on social media from parents or coaches looking to help a player “add 4-5 mph to their pitching speed” or “give a hitter an extra 50 feet of distance on their hits” in the next couple of months.

Sorry folks, it doesn’t work that way, unless their overall mechanics are so bad that any type of guidance will help them overcome some seriously limiting flaws.

The reality is improvement often comes in unnoticeable-to-the-naked-eye increments on a player who is already pretty good. Maybe it’s a slight relaxation of critical muscles that enable a little extra acceleration or a little better positioning of body parts than was achievable before.

Maybe it’s a little extra strength from workouts that doesn’t show up on a force plate or a radar. But it enables a quicker deceleration or a little more efficient transfer of energy from one segment to another or a little faster spin than was happening before that sets a player up for future success.

Stack enough of those little improvements together, one-by-one, and suddenly, before you know it, you have built them into something that will make people say “wow.”

Where it’s different, of course, is that fastpitch softball players can’t bring in a phalanx of slaves, convicts, soldiers, and peasants to do the work for them while they collect all the glory. They have to do the work themselves, repetition after repetition, whether it’s skill work, lifting, speed and agility, or whatever else they need.

The tough part is being patient throughout this process. We all want to see instant results – coaches as much as players and parents.

Again, though, it doesn’t work that way (at least 99.999% of the time). It would be like carrying a bunch of bricks over to where you’re building your wall and trying to stack them all at once.

The result is probably not going to last for nearly 3,000 years and draw visitors from all over the world. In fact, it probably won’t last a day and the only visitor it will draw is the local building inspector telling you to tear it down and try again.

There are no miracle cures or programs that will instantly take a player from zero to hero. What it does take is time and focused work, doing what you’re supposed to do to the best of your abilities each so that over time those individual efforts pay off into a larger, more effective, and more satisfying whole.

So keep stacking those bricks. And be sure to appreciate and celebrate even the smallest victories – even if they’re just a movement feeling better than it did before.

The journey will be worth it when you see the incredible structure you’ve built.

Great wall photo by Ella Wei on Pexels.com

Buying Tools v Learning to Use Them

Like many guys, at one time in my life I thought woodworking would be a great, fun hobby to learn. Clearly that was before my kids started playing sports.

So I started becoming a regular at Sears, Ace Hardware, Home Depot, Menards, Lowes, and other stores that sold woodworking tools. YouTube wasn’t a thing back then (yes, I am THAT old), so I also bought books and magazines that explained how to do various projects.

Here’s the thing, though. I might skim through the books or an article in a magazine to give me just enough knowledge of which end of the tool to hold, then I’d jump right in and start doing the project.

Needless to say, the projects I did never quite came out the way the ones in the pictures did. I also didn’t progress much beyond simple decorative shelves and things like that – although the ones I did make held up for a long time.

The thing I discovered was that buying new tools was a lot easier, and a lot more fun, than learning how to use them. Buying tools is essentially “retail therapy” for people who aren’t into clothes or shoes. And you always think if you just had this tool, or this router bit, or this fancy electronic level, everything will come out better.

Nope. Because no matter how good the tool or accessory is, it still requires some level of skill to use it.

Fastpitch softball parents and players often suffer from the same affliction. They believe that if they get the latest version of expensive bat they will hit better.

They believe if they purchase this gadget they saw promoted on social media it will automatically cure their poor throwing mechanics. They believe if they purchase this heavily advertised pair of cleats they will automatically run faster and cut sharper.

Again, nope. New softball tools like bats and balls with parachutes attached and arm restricting devices and high-end cleats are certainly fun to buy, and there’s nothing like the anticipation and thrill of seeing that Amazon or FedEx or UPS truck coming down the street to make you want to burst into song.

But they’re just tools. In order to get the benefits of those tools you have to learn how to use them correctly then work with them day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year.

And as we all know, that part isn’t as much fun. There’s a reason it’s called the grind.

Take that bright, shiny $500 bat. If you’re still using a $5 swing, or you’re too timid to even take it off your shoulder, it’s not going to do you much good. It may look pretty but you could be using a $50 bat to the same effect.

You have to get out and practice with it. Not just during practice but even when no one is around. The more you do it the better you’ll get at learning how to use it – just like I discovered with my fancy jigsaw.

Pitching, fielding, throwing, baserunning, it’s all the same. No fancy glove or high tech gadget is going to help you get better no matter how much it costs. You have to learn how to use it, which means getting off your butt (or off your screen) and using it.

If you don’t know how to use it, seek out somebody who does and have them help you. It’s a pretty good way to shortcut the learning process, and often a better way to invest your time and money.

Yup, sure, new tools and toys are a lot of fun to wish for and shop for and buy. But even the best ones can quickly become shelfware if you’re expecting them to do all the work for you.

Get the tools that will help you get the job done, but always remember you have to learn how to use them to reap the full rewards. Otherwise you’re just throwing away money.

The Path to Improvement Is Rarely Linear

So you decided to start taking your daughter to private lessons, or to buy an online package, or do a bunch of research and teach her yourself. That’s terrific – way to step up and help your daughter get better at the sport she loves.

Now it’s time to set some realistic expectations. In my experience, when people think of improvement in sports through lessons, more practice time, etc. they tend to expect it will look like this:

When the reality is it’s far more likely to look like this:

So why can’t it be more linear in the classic “hockey stick” style, especially if you’re putting in the work? Why does it seem like it always has be be two steps forward and one step back?

A lot of it comes down to two things: human nature, and how the human body (and the brain that controls it) works.

Humans are amazingly adaptable to their environments. We can learn how to accomplish incredible things based on what our goals are.

Once we’ve learned how to do those things, however, we tend to internalize the movements that got us there. Which means we stick with them even if the goals have changed.

Let’s take a young pitcher, for example. All her coach really wants from his/her young pitchers is for them to get the ball over the plate, i.e., throw strikes.

“We can’t defend a walk,” the coach keeps calling out, so the pitcher starts using her body in a way that allows her to accomplish the #1 goal – throwing strikes. Doesn’t matter if the movement to do so is efficient, or yields a pitch velocity that makes everyone say “Wow!” or even results in many strikeouts or weak hits.

As long as there are no walks the coach is happy, and the pitcher is a star who gets the bulk of the innings.

Sooner rather than later, however, that strategy is no longer good enough. The pitcher is getting pounded by hitters who can blast a meatball coming over the heart of the plate, so she needs to learn to throw harder, hit spots, and eventually spin the ball too if she wants to continue getting innings.

Unfortunately, the movement patterns that made her so effective at age 9 or 10 are not very conducive to throwing hard or hitting spots or spinning the ball. So she now has to learn new movement patterns.

Only she’s kind of locked into the old ones, and since her body and brain remember that those patterns were great at accomplishing the goals associated with the pitching motion at that time they’re having a hard time giving them up. We are a product of our habits, after all.

As a result, the pitcher’s performance could drop down for a while as she attempts to replace old movement patterns with new ones. Sure, the new patterns will yield more success in the long term by making her movements more efficient and effective, which will make it easier to perform at a higher level.

But it could be discouraging as she sees that temporary performance dip while her body re-learns how to move to accomplish something that used to seem easy and familiar.

The same is true with every aspect of fastpitch softball – hitting, overhand throwing, fielding, even running and sliding. Because before you can achieve any type of improvement you first have to change what you’re already doing, no matter how successful it has been in the past, and change is hard.

At this point you may be wondering if there is a statute of limitations on the backward steps. After all, once you get to a certain level of competence, or even excellence, shouldn’t it be easier to just keep going up without hitting a plateau or (gasp!) seeing performance go down?

No, for the same reasons it’s a problem in the beginning stages. In order to drive improvement, even for those at the highest levels, you have to change something you’re doing, because as the adage says, if you do what you always did you get what you always got.

In fact, it may be tougher at the higher levels because there is more to lose. A player has to decide if the potential improvement to be gained is worth the risk of a temporary loss of performance – especially if that performance has been serving the player well.

Doing something different in a high-pressure situation is likely to result in at least a slight loss in confidence due to its unfamiliarity, which leads to not putting in the same level of effort as the player would with the more comfortable movements. She may also lose some energy temporarily because she now has to think about what she’s doing rather than simply executing the movements at 100% effort with no thought involved.

That’s why high-level players usually make these changes in the offseason.

A high-level player won’t take on that risk, though, without a clear view of the rewards on the other side. She will also have been through the process before too, so should understand the ups and downs of continuous performance improvement.

Sure, it would be great if making changes automatically resulted in an immediate improvement in performance. While that can happen sometimes, more often than not it takes some time (and some missteps) before the benefits of all that work show up on the radar or in the box score.

But just like a butterfly emerging from a cocoon, if you put in the work on the right things, and remain patient, the reward will be there on the other side.

My good friend Jay Bolden and I have started a new podcast called “From the Coach’s Mouth” where we interview coaches from all areas and levels of fastpitch softball as well as others who may not be fastpitch people but have lots of interesting ideas to contribute.

You can find it here on Spotify, as well as on Apple Podcasts, Pandora, Stitcher, iHeart Radio, or wherever you get your podcasts. If you’re searching, be sure to put the name in quotes, i.e., “From the Coach’s Mouth” so it goes directly to it.

Give it a listen and let us know what you think. And be sure to hit the Like button and subscribe to Life in the Fastpitch Lane for more content like this.

Butterfly Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

How Practice Helps Shorten the Trip to Softball Success

At the end of the first lesson with a new student I will often ask her if she knows where New York City and Los Angeles are on a map. I know that’s a gamble given how famously bad we Americans are at geography, but even if she doesn’t know she will usually have an idea of what the U.S. looks like and I can show her Los Angeles is way on the left and New York City is way on the right .

I will then ask her how many different ways there are to get from New York to Los Angeles. Most understand I mean modes of travel, although the ones who are just learning to drive may panic thinking I’m looking for turn-by-turn directions. I’m not that cruel.

Once she understands the question we’ll start listing them out: flying, driving, train, boat, bus, etc. I will also remind her you can walk, run, or bicycle as well.

The final question is, “Which way is the fastest?” Pretty much everyone says “flying,” although there’s an occasional outlier who has to be corrected. That’s when I swoop in with the point.

“If you practice at least two or three times a week between lessons, it’s like flying from New York to Los Angeles,” I tell her. “You’ll get to your destination quickly and refreshed, and be ready to go on and do better things than travel.

“But,” I will continue, “if you only pick up a bat or a ball or a glove when you have a lesson it’s like walking from New York to Los Angeles. You’ll still get to where you’re going, but it will take a lot more time and it will be a lot more painful and frustrating.”

In my mind, that may be the most important thing I teach these young ladies when they come to me. I think players and even parents often have an expectation that if they take lessons, especially from a coach who’s a “name,” it will automatically make them great.

Nothing is further from the truth, however. They may get a little bit better over time but it’s going to be a long time before they notice any substantial improvements.

But if they put in the work on their own that’s where they’re going to see real progress. Because that’s where the real magic happens.

Continuing the transportation theme, I tend to think of coaches as the GPS for the journey. They will give you information, even turn-by-turn directions, so to speak, that will guide players to their desired destination.

Nothing happens, however, until the player puts the “vehicle” (her body) in gear and starts driving toward the destination. Just like with the car, if she just sits there without doing something the directions will be the same day after day, week after week, month after month, etc. instead of moving onward.

A coach shouldn’t be watching his/her players work on last week’s assignment for the first time. The player should have already put in the work on it.

That doesn’t mean the player will necessarily have it mastered after a week or two. But there should be progress toward the goal so the coach is performing a process of continuous refinement – chipping away at the goal layer by layer the way a sculptor chips away at a piece of marble until it turns into a breathtaking work of art.

If the coach has to keep chipping away at the same level of skill, however, progress will be slow and the player is likely to get frustrated and stop long before she turns into the masterpiece she should be.

It can be difficult for players, especially the young ones, to understand the abstract concept of how quality practice leads to excellence. But everyone understand travel, because we all go somewhere every day.

If you have a player (or child) who doesn’t seem to see the need for practice, try the map analogy. It might just help get her moving in the right direction.

My good friend Jay Bolden and I have started a new podcast called “From the Coach’s Mouth” where we interview coaches from all areas and levels of fastpitch softball as well as others who may not be fastpitch people but have lots of interesting ideas to contribute.

You can find it here on Spotify, as well as on Apple Podcasts, Pandora, Stitcher, iHeart Radio, or wherever you get your podcasts. If you’re searching, be sure to put the name in quotes, i.e., “From the Coach’s Mouth” so it goes directly to it.

Give it a listen and let us know what you think. And be sure to hit the Like button and subscribe to Life in the Fastpitch Lane for more content like this.

US map graphic by User:Wapcaplet, edited by User:Ed g2s, User:Dbenbenn – File:Map_of_USA_with_state_names_2.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=81990933

Surviving “One More” Syndrome

Friends, today we are gathered to address one of the most dreaded issues in all of fastpitch softball practice. Of course, I am talking about “One More” Syndrome.

It’s an issue that affects nearly every player at all levels at one time or another. You may not know it by name, but you know its effect.

There you are, working on hitting, pitching, fielding, or some other skill. You’ve had a very successful session when the coach (or a parent) announces “one more,” as in one more pitch to a hitter, one more ground ball to a fielder, one more rep of a particular pitch.

Suddenly it is as if you’ve never seen a softball before in your life, much less have hit, caught, or thrown one. Whatever skill you were executing with tremendous ability has completely abandoned you, leaving you flapping around the field like a drunken penguin.

This is a topic that came up during a lesson last night with a pitcher named Brooklyn. She was cruising along pretty well working on her changeup when I said, “Ok let’s throw one more” – at which point she totally tanked the pitch.

Brooklyn looked at me, smiled, shrugged, and asked, “What is it about saying one more that makes things go bad?” I had to admit I didn’t know, but it does seem to happen a lot. That’s when we came up with the idea of One More Syndrome.

So what can you do about it? One thing is not to put too much worry into it.

For whatever reason, this seems to be a very common affliction. If it was odd that would be one thing. But it pretty much happens to everyone sooner or later.

If you really want to put a stop to it, though, your best bet is probably just not to think about the fact that it’s the last whatever. Just treat it like one more rep and you’ll most likely be fine.

Worst case, just ask the coach or parent not to announce it’s the last one – at least all the time. That way you can work up to the mental toughness not to be affected so you can keep things moving along quickly.

“One More” syndrome is real. But it doesn’t have to be a terrible issue.

Just laugh about it and get on with your practice. Eventually you’ll get to the point where hearing “let’s do one more” will be just another ordinary phrase.

The Power of Using Video When You Practice

One of the tools I use the most when I give lessons is my iPhone. If I see a player making some sort of awkward or inefficient movement, out comes the ol’ phone and I immediately shoot a video I can show that player (and often her parent, guardian, team coach, etc.).

Now, I can stand there and tell the player what she’s doing without using video, but often it seems like they either think I’m exaggerating the movement they’re making or I am making it up entirely. I said that because it has little impact on what they’re doing, and they frequently will go right back to doing it.

But when they see the video, they suddenly know I was not exaggerating for comic effect but if anything was dialed back a bit on it. Seeing is believing, and believing enables them to start making the correction. Things usually get better from there.

That’s great during lessons. But what about the other 90% of the time, when the player is practicing on her own or with a teammate, parent, guardian, team coach, etc.?

There is a solution that will help shortcut the time-to-improvement. It involves a little practice secret that I’m now going to share with you.

The Revelation

These days pretty much everyone’s personal phone has the ability to shoot video. And those video capabilities can be used for more than a Snapchat or a Tik Tok dance video.

Why not set up the phone to the video setting, hit the “Record” button, then take a video of whatever skill she is trying to master? Then she can play it back, watch herself, and see if she is leading with her hips (if she is a hitter), getting some elbow bend over the back side of the circle (if she is a pitcher), or making whatever movement she is supposed to be making at whatever point she’s working on.

I know, genius, right?

Sure, when I shoot video I use the OnForm app so I can easily slow it down, scrub it back and forth, draw on it, measure angles, or do whatever else I need to do. It’s really cool to be able to do that, as I describe here.

But you don’t absolutely need all of that, especially if your coach has told what to look for/work on specifically. The basic video any smart device shoots is enough to give you eyes to see what’s happening and whether the movements that player is making are the movements that player SHOULD be making.

I know on an iPhone you can even scrub it back and forth by tapping on the video and then using one finger to move the little frames at the bottom back and forth. I imagine Android and other operating systems offer the same capabilities.

Different Learning Styles

So what makes video so valuable?

Science has documented that different people learn in different ways. Some of us learn better from reading directions. (Most of those people tend not to be male, as most males tend to jump in first and then only read directions when they get in trouble – usually halfway through the project.)

Some learn better from hearing things explained, the way it would typically happen in a lesson or team practice. “Suzy, you have to get your butt down on the ball.”

Some learn best by actually performing the skill we are attempting to perform. Although in my experience a lot of young players actually have trouble feeling whether they are doing something correctly while they are in the middle of it.

But the vast majority of us (65%) are visual learners. If we see it, we can understand what we’re supposed to do, or what we’re not doing now, better.

Yet when it comes to actual practice sessions, players and coaches rely almost entirely on the two weakest preferences for learning – auditory/listening to instructions (30%) or kinesthetic/doing it and feeling it (5%). Doesn’t make much sense, does it?

By incorporating video into the learning process players can learn faster by using the method most prefer. And even if they are in the other 35%, augmenting auditory and/or kinesthetic instruction with video is neutral at worst and a plus beyond that.

Video Power in Your Pocket

The beauty of all this is that it doesn’t require a lot of work. Today’s teen or preteen carries more video power in her pocket or purse than was available when Debbie Doom (yes, that was her real name, and what a great name it was) was dominating hitters, Lisa Fernandez and Sheila Cornell-Douty were winning gold medals in the Olympics, and Linda Lensch was becoming a USA Softball Hall of Famer.

All you have to do is take that device out of wherever it is, prop it against a nearby bench, bat bag, or rock, and hit “record!” Then you have instant feedback on where you are and whether what you’re practicing is making the player better – or worse.

She can even do it by herself. And if the coach says it’s ok, she can even send it to the coach’s phone or other device to receive additional feedback to make sure she stays on track.

That’s sure a lot faster and easier than the early 2000s, when I started coaching. Back then it was a production.

I had to bring a laptop and separate video camera, set up the camera on a tripod, connect the video feed to the laptop and then whatever video tool I was using, and then manipulate it all to run it back. I had to plan it all ahead too, and hope an errant throw didn’t knock out the camera or laptop.

Now it’s just pull out the phone, open the app, shoot, and review.

Opportunity Knocks

The opportunity here is tremendous, and the cost is nil if you already have a phone or tablet. So why wouldn’t you take advantage of it?

By incorporating video into their practice sessions players can learn more effectively – and reach their goals faster.

Seems like a no-brainer to me.

Phone photo by Wendy Wei on Pexels.com

Greatness Comes With A Cost

A whole bunch of years ago there was a series on cable called Camelot. It was yet another retelling of the King Arthur legend, although with a grittier feel to it.

Of course one of the key characters was Merlin, the King’s magician/adviser. Normally he is portrayed as someone who can wave his hands or wand or whatever and easily conjure up whatever is needed at the time.

But in Camelot it didn’t happen quite so simply. On the rare occasions when Merlin needed to summon up some magic, it took all his concentration and an extreme effort, which would often see him bleeding from his eye before he finished.

When asked about it, he would painfully reply, “Magic has a cost.”

The same is true for learning how to play fastpitch softball. (You knew there had to be a point to this story somewhere.)

If you want to be great at it, or even really, really good, you don’t simply walk out onto the field and start playing. There is a cost to achieving greatness – a price to be paid in exchange for the glory you seek.

Often that price is paid in time. You may stay need to stay after practice when everyone else is going home to get some extra reps in or solve a particular issue.

It likely will also involve working on your own, even when you don’t feel like it, to improve a skill that’s deficient or take one that’s good to the next level. (Often the second one is tougher to get going on than the first, because it’s easy to convince yourself you’re already good enough.)

The price may come in terms of missed opportunities for other things. While your friends are all going to a concert or an amusement park or a birthday party or some other fun event, you’re going to a college camp or a tournament or maybe even staying behind because your team has practice.

The price could be financial. If your family doesn’t have a lot of disposable income you may need to pass on that new phone or skip getting a new outfit so you can pay for team fees or a new bat or a college camp – anything that’s outside of the core fees.

Or it could mean you’re not able to get a job to make some “fun” money of your own because your practice and game schedule doesn’t allow it.

The price could be pain from a particularly tough speed and agility class or perhaps the result of an injury – especially if you’re attempting to play through it. Or it could be the feeling of being tired all the time.

College players experience that a lot. Between early morning lifting, classes, practice (team or on their own depending on the time of year), study tables, and making up for lost time in the classroom due to games they can pretty much be in a fog much of the year.

The cost can manifest itself in many ways. But there is always a cost if you have that burning desire to stand out on the field and do all you can to help your team win.

This isn’t just for players, by the way. There is also a cost is you want to be a better coach.

You will find yourself putting in far more time than just the couple of hours at the field a few days a week or even the 12-hour days of a tournament. There’s practice planning, coordinating schedules, managing budgets, talking to parents and players, and a whole host of other tasks to be performed while still trying to stay employed at your day job.

If you want to be great you also have to allow for continuing education. You’ll need to take online courses or attend in-person clinics such as those offered by the National Fastpitch Coaches Association as well as local events.

You’ll invest an inordinate amount of your own money on books and videos as well as training devices – even if it seems they will solve one problem for one player.

And, of course, at some point you will miss a family birthday, or a school reunion, or a work outing, or something else because, well, games. At which point the cost will also include the internal stress it puts on your personal relationships because “you’re always at some field somewhere” instead of where others think you should be.

So is achieving your goals on the field worth the cost? Only you can answer that.

The key, though, is to understand that there will be a cost if you want to aspire to greatness – or even “really, really goodness.”

Your willingness to pay it is where the true magic happens.

Magician photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels.com