Blog Archives

What It Takes to Really Learn Something (or Unlearn Something)

When I was but a lad heading into high school, my heart’s greatest desire was to learn how to play the guitar. Partially because I loved music, but also because I thought doing so would help me meet girls.

(Don’t judge, Eddie van Halen started on guitar for the same reason, although he did a little better than me on learning it.)

Anyway, for my 14th birthday (just as the summer started) my parents bought me the cheapest piece of junk available that will still work, a $20 Decca guitar from Kmart. But I didn’t care – I had a guitar, along with a little songbook with songs like Born Free and Red River Valley that had the little finger placement charts above every chord.

I pretty much spent the entire summer locked in my room for 4-6 hours a day every day, playing the same old songs over and over until they began to sound like actual songs. In a month I felt comfortable enough to play that guitar in front of my parents and a couple of their friends.

Within a couple of months of starting I bought my first “real” guitar for $100 out of my 8th grade graduation money – a Suzuki 12 string that I still own to this day. It’s not very playable anymore but I still keep it around for sentimental reasons.

I tell you this story to point out a valuable lesson: if you really want to get good at something, you can’t just dabble at it or put in time against a clock. You have to work at it deliberately, with a goal and a sense of purpose.

In other words, you have to know your “why” or you’re just going to spin your wheels.

So if you’re a pitcher who is trying to increase her speed or learn a new pitch, you can’t just go through the motions doing what you always did. You can’t just set a timer and stop when the timer goes off.

You have to dig in there and keep working at it until you make the changes you need to make to reach your goal.

If you’re trying to convert from hello elbow to internal rotation, you can’t just throw pitches from full distance and hope it’s going to happen. You have to get in close, maybe slow yourself down for a bit, and work on things like upper arm compression and especially forearm pronation until you can do them without being aware of them.

It might take a few hours or it might take a month of focused, deliberate practice. But you have to be willing to do whatever it takes to get there.

The same goes for hitters. If you’re dropping your hands as you swing or using your arms instead of your body to initiate the swing you’re not going to change that overnight by wishing for it.

You have to get in there and work at it, and keep working at it until you can execute that part of hitting correctly. No excuses, no compromises; if you want to hit like a champion you have to work like a champion.

There will sometimes be barriers that seem insurmountable, and no doubt you’ll get frustrated. But there is some little thing holding you back and you attack it with ferocity, with a mindset you won’t let it defeat you, sooner or later you will get it and be able to move on to the next piece.

When I first learned how to play an “F” chord it was really difficult. It requires you to use your fingers in ways other chords don’t, especially when you’re a beginner.

But I needed to master that “F” chord cleanly so I could play certain songs, so as physically painful as it was (especially on that cheap little Decca guitar) I kept at it for hours on end until it was just another chord among many in the song.

The same will happen for you if you work at it. The thing you can’t do today will become easy and natural, and that will put you in a better position to achieve your larger goals.

Yes, it takes a lot to make a change, especially if it’s from something you’ve been doing for a long time. Old habits die hard as they say.

But if you approach it with passion and purpose you’ll get there – and you’ll be better-positioned for your next challenge. .

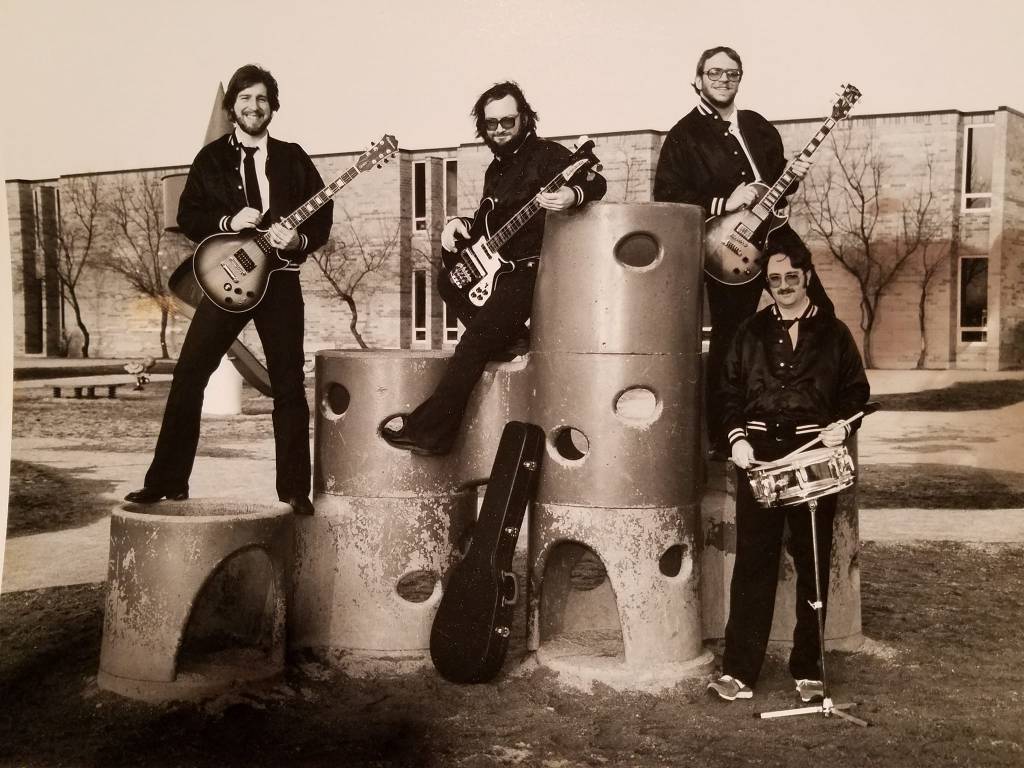

BONUS CHALLENGE: Yes, one of those young fellows up there in the top photo is me. See if you can guess which one and put your choice in the comments below. (HINT: It may not be the one you think.)

Easing Young Arms Into the Season

On our From the Coach’s Mouth podcast yesterday, Jay Bolden (St. Xavier University, BeBold Fastpitch) and I discussed several topics related to the start of the high school and outdoor travel season. During that conversation Jay brought up a topic that I believe is critical to both the health of the athletes and the success of the team over the long haul: the importance of easing young arms into the season.

I get how challenging that can be, especially for high school (or college, for that matter) coaches. You get a couple of weeks with your athletes and then you have to start playing games.

In that couple of weeks, you have a mountain of things you feel you need to go over or get done to be prepared for the start off the season, and many of them involve overhand throwing. In the heat of those preparations it’s easy to lose track of just how much stress is being placed on those arms and shoulders – stress they are not ready for even with the best of arm care programs.

Let’s start with your athletes who are softball-only. During the offseason they have probably been practicing 1-3 times per week, which is very different than the six times per week a high school or college team will practice/play. Or a travel team will play in the summer.

Within that time they may or may not have done some arm care exercises as part of their warm-up and cool-down, but kids being kids they probably didn’t approach it with the same level of intensity they would in-season. Even if they did, though, there’s only so much an arm care program can do.

For example, one of my students is very diligent about her arm care program. But one weekend in the fall she went to a college camp where they spent three hours doing non-stop overhand throwing.

She came back with a sore shoulder that ended up requiring her to take some time off from overhand throwing and pitching while she did physical training to relieve the pain and repair the damage. Fortunately she was able to recover but it definitely set her back some.

Now imagine all the players who didn’t do that much arm care, or didn’t put in the effort to do it right when they did it. They’re not prepared to suddenly start throwing intensely in speed drills or distance drills day after day after day.

It won’t take long before they’re in some level of pain. Keep it up and by halfway through the season you may have a few athletes on the IR list and others who are gritting their teeth just trying to make it through the end of the season. Not exactly the formula for a long run to state.

Another complicating factor for many teams is the transition from indoor to outdoor practice. If you live in California, or Arizona, or Florida, or another area with warm temperatures during the winter it may not be a big deal.

But for those going from throwing in a cage or a small practice are to a full-size field it can be a huge risk factor. A little over-enthusiasm on the part of the coach can have even the best cared-for arms dragging in short order.

Then there are the athletes who come to softball after playing another overhead sport such as basketball or volleyball. Whether it was a school team or a club team, those other sports with their intense schedules have probably put a lot of stress on the shoulder joints.

There is a high risk for labrum tears, bicep tendonitis, and other issues even before you start lengthy practices involving throwing. You could easily lose a couple of your best overall athletes before the season starts even if the softball-only players are doing ok.

So what can you do to avoid these issues while still getting your team ready to play? Jay had a great suggestion that he uses with his teams.

For starters, during fielding practice have buckets available near the fielders on some days, especially early in the pre-season. When you hit fly balls or ground balls, instead of having your players throw the ball back to the fungo hitter have them toss the ball in a bucket.

When the fielder’s bucket is full, have one of them run it back in to the hitter and take the empty bucket out. That way you get the fielding work done while reducing the strain on the arms and shoulders.

You can also spend time working on short tosses, the type you would do when one player is close to another and doesn’t need to make a full through. This part of the game is probably under-practiced by most teams, so it has the added benefit of shoring up a potential problem area while saving wear-and-tear.

It can also be fun if you work on a variety of throws. Jay mentioned hearing a coach at a clinic suggesting you can also work on crazy situations such as the glove scoop and toss or throwing behind your back.

Not all the time, obviously, but every now and then just to spice up practice a little. Think Savannah Bananas.

Dailies are another great way to get fielding practice in for infielders without stressing arms. You can get a lot of reps for straight-in, forehand, and backhand fielding in in a short amount of time – and with no stress to arms or shoulders. Although it can be a little tough on the knees.

Along the way, do your best to address throwing mechanics as well. If you’re not sure how to teach good mechanics ask a more experienced coach or check out programs such as Austin Wasserman’s High Level Throwing program to learn how to set up an organized, structed throwing program designed to ensure your athletes’ long-term arm health.

Finally, as with any other type of strenuous exercise program, be smart about what you’re doing. Start with low intensity activities and lower reps, then build your way up to more reps and longer throws.

A commonly quoted statistic is that 80% of all errors in baseball and softball are throwing errors. I couldn’t find a source to absolutely confirm it, but based on my experience it certainly sounds correct.

While some of those errors are no doubt just flat-out mistakes, I’d bet if you looked under the surface a fair percentage could be attributed to arms that are sore or just plain tired. Help your players go into the long season with healthy (or at least healthier) arms and you’ll be far more likely to make a deeper run into the postseason.

There’s More to Calling Pitches than Calling Pitches

One of my favorite jokes is about a guy who goes to prison for the first time. As he’s being walked to his cell by a guard he hears a prisoner yell “43!”, which is followed by howls of laughter from the rest of the population.

About 20 seconds later someone else yells out “17!” and again there is laughter. After a couple more numbers are called out the new guy asks his escort what that’s all about.

“A lot of our population has been here a long time and has heard the same jokes over and over,” the guard explains. “To save time, each joke has now been assigned a number. Someone yells the number and the rest react to the joke.”

“Hmmm,” the new guy says to himself, “seems like a good way to try to fit it on day one.” So he takes a deep breath and calls out “26!”, which is followed by silence.

“What happened?” he asks the guard. “Why didn’t anyone laugh?”

To which the guard replies sadly, “I guess some people just don’t know how to tell a joke.”

The same can be said for pitch calling in fastpitch softball. While it might seem straightforward, especially with all the data and charts and documentation available (including this one from me), it’s actually not quite that simple.

The fact is pitch calling is as much art and feel as it is science and data, and like the newbie prisoner trying to fit in, some people have a natural knack for it and some don’t.

That can be a problem because nothing can take down a good or even great pitcher faster than a poor pitch caller.

Here’s an example. There are coaches all over the fastpitch world who apparently believe that pitch speed is everything. As a result, they don’t like to (and in some cases refuse to) call changeups because they believe the only way to get hitters out is to blow the ball by them.

But the reality is even a changeup that’s only fair, or doesn’t get thrown reliably enough for a strike, can still be effective – as long as it’s setting up the next pitch. And if that changeup is a strong one, it can do more to get hitters out than a steady diet of speed. Just ask NiJaree Canady, who can throw 73 mph+ through an entire game but instead leaned heavily on her changeup during the 2024 Women’s College World Series.

The reality is the ability to change speeds, even if it’s going from slow to slower, will be a lot more effective in most cases than having the pitcher throw every pitch at the same speed no matter how fast she is. Sooner or later good hitters will latch onto that speed and the hits will start coming.

There’s also the problem of coaches falling into pitch calling patterns. Remember that great change we were just talking about?

If you’re calling that pitch on every hitter and hitters are having trouble hitting your pitcher’s speed, the hitters can just sit on the changeup and not worry about the rest. It gets even worse if you’re calling a particular pitch on the same count all the time.

A truly great pitch caller is one who can look at a hitter and just feel her weaknesses. That great pitch caller can also see what the last pitch did to the hitter and call the next pitch to throw that hitter off even more.

I’ve watched it happen. When my younger daughter Kim was playing high school ball she had an assistant coach who was a great pitch caller.

She was never overpowering, but she could spot and spin the ball. The coach calling pitches knew her capabilities, and when they went up against a local powerhouse team that had been killing her high school the last few years he used those capabilities to best advantage.

The team lost 2-1, due to errors I might add, but that was a lot better than the 12-1 drubbings they were used to. The coach called pitches to keep the opposing hitters guessing and off-balance all game, Kim executed them beautifully, and they almost pulled off the upset.

The coach didn’t have a big book of tendencies, by the way. He just knew how to take whatever his pitchers had and use it most effectively.

And I guess that’s the last point I want to make. All too often pitch callers think pitchers need to have all these different pitches to be effective.

While that can help, a great pitch caller works with whatever he/she has. If the pitcher only has a fastball and a change, the pitch caller will move the ball around the zone and change speeds seemingly at random.

The hitter can never get comfortable because it’s difficult to cover the entire strike zone effectively.

Add in a drop ball that looks like a fastball coming in and you have a lot to work with. In fact, for some pitch callers that’s about all they can really handle; throw in more pitches and they’re likely not going to understand how to combine them effectively to get hitters out.

Some people have the ability to call pitches natively. They just understand it at the molecular level.

For the rest, it’s a skill that can be learned but you have to put in the time and effort to get good at it, just like the pitchers do to learn the pitches.

Watch games and see how top teams are calling pitches. Track what they’re throwing when – and why.

Look at the hitters, they way they swing the bat, the way they warm up in the on-deck circle, the way they walk, the way they stand, the way they more. All of those parameters will give you clues as to which pitches will work on them.

Then, make sure you understand how they work together for each pitcher. For example, maybe pitcher A doesn’t have a great changeup she can throw for a low strike, but the change of speed or elevation may be just enough to make a high fastball harder to hit on the next pitch.

Your pitchers aren’t robots, they are flesh and blood people. So are the hitters. If you understand what you want to throw and why in each situation you’ll be on your way to becoming a legend as a pitch caller – and a coach your pitchers trust to help them through good times and bad.

Take the Time to Grind

Take a look at any list of what champions supposedly do (such as this one) and somewhere on there you’ll see something about how they do the things others aren’t willing to do. What those lists don’t tell you, however, is a lot of those things they’re referencing fall into the category of “grinding.”

This isn’t the flashy stuff. They’re not spending hours on the Hit Trax machine, playing more games, participating in fancy clinics, etc.

Instead, they are working over and over to correct even the tiniest flaws, perfect their mechanics, and learn to get everything they can out of themselves.

If that sounds boring it’s because it is. That’s why most players don’t do it – especially if they are already experiencing success.

A player who is the best hitter on her team, or maybe even in her league or conference, may hear that she needs to work on improving her sequencing. But she also wonders why bother since she’s already leading in most offensive categories.

Sure, there’s always that story that it won’t work at “the next level.” But there’s no guarantee that’s actually true, so until she experiences failure she may decide that’s just the softball version of the Krampus – a myth created to scare people into doing what you want.

True champions, however, don’t do things because they’re afraid of failing at the proverbial “next level.” They do them because they want to be the best they can be, at which point everything else will take care of itself.

Here’s an example. A typical pitcher will look at her speed numbers, and as long as they are where they need to be they’re happy. Someone willing to grind, however, will actually allow her speed to slip a little to improve her drive mechanics or her arm circle. That way, when she has internalize the change she will be even faster and more accurate.

For a field player, it could be learning to throw better by learning a better throwing pattern.

For a hitter it could be reworking the structure of her arms to prevent her back elbow from getting ahead of her arms. That’s not sexy, and it’s certainly nothing most people would notice if they weren’t watching high-speed video.

But the champion knows she’ll hit the ball a little harder, and with greater consistency, if she makes the change so she spends the time to do it. As opposed to average player who tries it a few times, gets bored with it, and goes back to trying to hit bombs off the tee.

And there’s the key difference. Grinding on mechanics can be mind-numbingly boring. It can also be incredibly different, especially as the things you’re grinding on become more nuanced.

It can also feel risky, because there’s a good chance that you will get worse before you get better – especially if what you’re changing is a fundamental process. If you’re in the middle of your season, that’s a huge risk to take (if you’re already experiencing success; if you’re failing, not so much).

That’s what makes the months between fall ball and the new year the perfect time to take on a grinding effort.

Early in the learning process you’re probably looking to make big changes that have a profound effect on your success in a game. It’s a bit easier to stay with it when that happens.

In other words, if you’re used to hitting weak ground balls and pop-ups in-between strikeouts, you have a lot of incentive to work at improvements. When you start hitting line drives to the outfield on a consistent basis it can be downright inspiring.

But if you’re already hitting line drives to the outfield, and you are now trying to hit more of them, it doesn’t feel quite as rewarding. Going from hitting .110 to .330 is a lot more noticeable than going from .400 to .440. Going from hitting zero doubles in three tournaments to four in one tournament is a lot more remarkable than going from four to six in one tournament.

That, however, is what those who are willing to grind do, because their reward is internal instead of external. For many, their goal is to be perfect. They want an extra base hit on every at bat, or a shutout for every game they pitch.

They know that goal is unrealistic, but they go for it anyway because they are driven to contribute as much as they can to the team and deliver the best results of which they’re capable.

The funny thing is, this is an individual decision. There are 100 ways to fake it, or to make it look like you’re grinding when you’re really not.

But for those who want to be the best they can be there’s no substitute for the grind. They make the effort to make smallest and even seemingly most insignificant improvements, because if they can gain an edge that will help them perform better and win more ballgames, they’re going to take it.

It’s really up to you. With a lot of teams shut down right now, either deliberately to give their players some time away or as a result of state orders, it’s the perfect time to grind away at something that will make you better.

Find something and put in the effort. You never know where it will lead you.