Category Archives: Pitching

The changeup smells fear

Had this discussion tonight with one of my students. I’d watched her a couple of weeks ago, and at that time it looked to me like she was telegraphing her changeup. The main way was slowing down as she threw it. It got hit most of the time, so I think it was a pretty good bet.

Tonight she and her dad came in, and the priority was the change. It’s a good pitch for her, and it just wasn’t working. I watched her throw one, then told her to try to go faster and throw it harder. That’s all it took. Boom! It was back and better than ever.

This is something I see a lot. Pitchers who are afraid the changeup won’t work tend to hesitate, which throws off the timing. At that point it won’t work, or at least it won’t work well.

That’s why I say the changeup smells fear. If you throw it with fear it won’t work. But if you put those doubts out of your mind and throw it hard, it will treat you right.

What a little experience and confidence can do

Last night I had one of those experiences that puts your heart in your throat at first, but then makes you glad you’re a coach.

One of my students, a girl named Lauren, told me she pitched again since the last time I’d seen her. (More on that in a minute.) Lauren has been taking lessons for a couple of years but never had much chance to pitch in games. Most of the time it was due to joining teams where they already had established, experienced pitchers, although she missed an opportunity in middle school because she was too shy to speak up and say she pitched.

As anyone who’s coached anything knows, at some point you just have to get in there and do it. This year, on her freshman HS team, Lauren finally got that opportunity. She throws hard, but was having some control trouble in practices that I would attribute to nerves as much as anything. The other pitchers on her team had game experience, but she didn’t have much.

Anyway, I went out to watch one of her games. She was the third pitcher in when her team was blowing out their opponents. She was a little amped up, and a little nervous, and had some trouble. Most of it was throwing high. She was bringing heat — looked to me that she was the fastest on either team — but she gave up a couple of walks early before finally settling down. I was a little worried that a risk-averse coach would decided he didn’t want to take the chance on another outing. Fortunately, that wasn’t true.

She told me she’d actually pitched twice since last week. The first game she got a couple of innings in. She walked a couple to start off, but then settled in and struck out the side, so no harm no foul.

She finally got a start after that. She told me she did well. Her mom, Brenda, however corrected that statement: she pitched a no-hitter. Lauren dismissed it because the team they played didn’t hit very well, but I told her a no-hitter is an accomplishment against anyone. Usually even a bad team has one or two kids who can hit, and even if they don’t some duck snort or ground ball with eyes leaks through.

So that’s very cool. It’s a testament to Lauren and her willingness to stick with it, even in the face of adversity and a lack of opportunity. When the opportunity came, she made the most of it.

By the way, the reason my heart was in my throat was when she started to describe her outings she made it seem like she did poorly. Totally suckered me in with that. I was quite relieved to hear she did well. I fully expect with some experience and confidence in her back pocket that she’s at the start of a long and successful career.

Everybody’s a pitching coach

Had an interesting one last night. One of my students mentioned that her HS coach (freshman level) wants her to use a different grip than the four-seam grip I’ve had her using. He (I think it’s a he) wants her to grip the ball along the runs instead. When I asked her why he wants her to do it to see if she’d been given an explanation she wasn’t sure at first. But then she remembered he’d said it would cause the ball to tail in or out.

All well and good. If you do it right that will work. But getting the ball to move away from the plate has not been the goal so far. Getting it to go where she intends it to go has been the challenge.

You see, although she is in high school she is just now learning to pitch. She’d taken lessons from someone or other a couple of years ago, but had to stop because it was hurting her wrist. (Too much emphasis on a forced wrist snap is my guess.) In any case, she has been taking lessons sporadically for the last three months or so. Most of that time was spent getting her to learn to throw the ball straight rather than having it go way out to the right every time. It was a battle, but she has finally gotten to the point where she can throw it for a strike consistently, and actually pitched a complete game not long ago.

My priority at this point is for her to develop speed to go along with it. It’s not that we haven’t emphasized that or worked toward it, but so far she hasn’t really gotten to the point mentally where she can just let go and throw. She’s still somewhat tentative. It’s getting better, but she can certainly drive her body harder and faster.

So the bottom line is, we’re still working on some fundamental issues. Encouraging her to change her grip to one that is less reliable in its result is only going to set her back, get her frustrated, and discourage her.

What her coach isn’t taking into account by showing this grip he probably heard in a clinic or saw on the Internet is her development level. It’s very important for an inexperienced pitcher to build confidence through success. As she becomes more confident she will go harder and become even more successful. And that means keeping it simple. New pitchers don’t need a lot of variables — like a ball that randomly tails off sometimes. They need to know where the ball is going when they throw it. The two-seam grip is much more appropriate for pitchers who already have good control, not those who are hoping for it.

By the way, this particular girl has a natural drop to her basic fastball. That’s probably more worth pursuing than in and out movement anyway.

So, the windmill pitching motion may not be as safe as everyone thought

A couple of people (including Frank Morelli) pointed me toward this article today from the Chicago Tribune. It’s about a recently completed study performed by a researcher at Chicago’s Rush University Medical Center that looked at the windmill pitching motion and injuries. The results absolutely contradict the prevailing notion that it’s ok for a 12 year old (or a 21 year old) to throw 80 innings in a weekend because the windmill pitching motion is natural and/or safe.

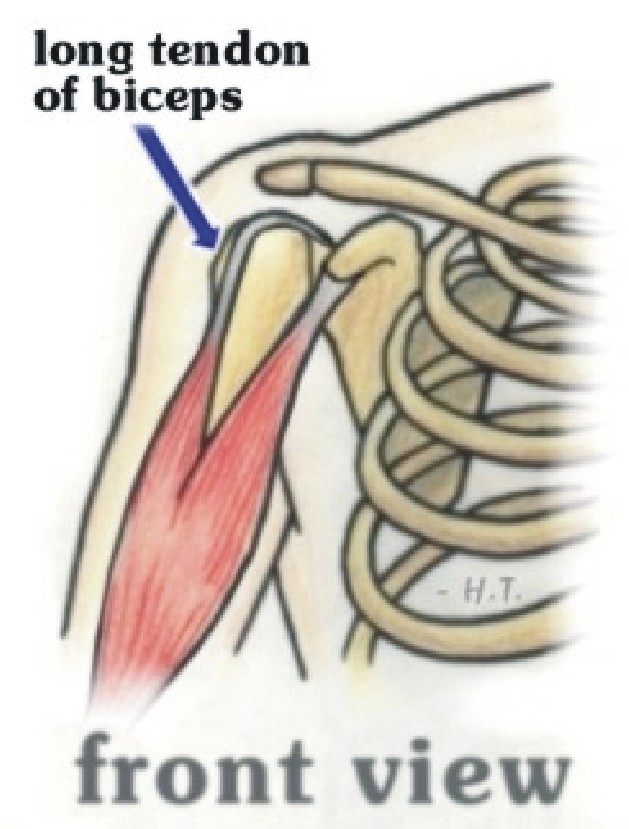

According to the study, it’s not. Dr. Nikhil Verma studied several pitchers, including some from the NPF’s Chicago Bandits, and concluded that the motion itself, particularly with unlimited repetition, can and does cause injuries. The most common is front shoulder pain driven by problems with the biceps tendon.

The article does a great job of explaining the study and what it found. I won’t rehash that here. But what I will say is that it’s no surprise. As I’ve said before, any repetitive motion is bound to cause wear and tear on the parts being used. If it didn’t, there wouldn’t be any Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. But that’s pretty common in office workers using a computer mouse. So it stands to reason that a violent, ballistic movement like windmill pitching would also cause damage and pain if repeated over and over. You’d have to be in total denial not to think so.

Every parent of a fastpitch pitcher should reach this article, print out a copy, and keep it handy on tournament weekends. Trophies are nice and all, but they’re not worth ruining a player’s career for, or leaving her with shoulder pain the rest of her life. I don’t care how good a shape you are in, or how gifted you are with good DNA. Repeating the same movements over and over and over, especially over a short period of time, is neither healthy nor smart. If you’re the parent of a 10U or 12U player especially, and your daughter’s coach wants to pitch her four or five games every weekend because “the team needs her” or “she’s our best chance to win,” you may want to rethink your team options.

Although the doctor believes it’s the motion itself that is the issue, I’m not so sure about that. A poor motion, yes. A pitcher who is trying for another two miles an hour by putting her body into an awkward position to get a little extra whip, yes. But a pitcher with good mechanics shouldn’t be in danger unless she simply repeats the motion so much she wears out the body parts involved.

Be smart. And remember: if your daughter pitches her team to glory at the expense of her shoulder this year, the coach will probably just go out and find some other kid to take her place next year. It happens.

More than one way…

Last night one of my students had one of those breakthroughs that make coaching so rewarding. Before I get into the breakthrough, allow me to give you a little background.

Rae Ann is a lefty who has been with me for a few years. Up until this year, I had her throwing a peel drop and a “cut under” curve among other pitches. The drop was ok, although it would often tend to come in a little low. She had good movement on it, though. But she really struggled to get the proper spin on the curve. She just couldn’t quite seem to get the hang of getting her arm into the proper position to get under it.

About halfway through the off-season I suggested we try throwing a curve where the hand comes over the ball instead of under. From what I saw, it seemed like that would work a little better. So we tried it. I told her flat out I didn’t have as much experience with this version, so we’d be learning together. My daughter Stefanie threw that curve when she was pitching, but I never paid much attention to the technique since I was just a bucket dad back then.

The first thing that happened is we wound up switching Rae Ann to a rollover drop. The first time she tried the curve she wound up throwing an awesome drop. It had great movement, very sharp, and came in more at the knees. She’s been throwing that ever since. But we still couldn’t quite get the sideways spin on the curve. We couldn’t really even get a drop curve spin. She pretty much came right over the top of the ball no matter what we tried.

Then last night I had an idea. We slowed down her motion, and I told her to imagine she had four foot long fingernails. Take those fingernails and trace an arc on the ground as she throws. The idea was to help her get around the ball rather than over it.

At first it had a minor effect. But as I let her work through it while I talked to her dad Matt, suddenly it came together. We got both proper spin and movement on the pitch. The cue of tracing the arc had helped her understand and visualize what she needed to do. I tried telling her before to come around the ball, but she didn’t feel it and it never helped. Having something visual, however, did seem to work.

So there you go. As a coach you’re constantly challenged to communicate techniques, ideas and other things to your players. You can’t just settle for what’s worked before. With a little persistence, and a little imagination, there’s always a way. You just have to find it. Expecting players to just “snap to” to what you’re saying is a bad way to go. Work with what they can understand and you’ll see the results.

Sharpening the rollover drop

As I have mentioned before, one of the ongoing challenges of coaching is finding new ways to say the same thing. It goes back to Einstein’s definition of insanity — doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.

In the area of coaching, you will have a way of explaining something that works. Then all of a sudden it doesn’t for one student. No matter how many times you repeat the same phrase, it doesn’t seem to do any good. Insanity. So you have to find another way to obtain the results you want.

Recently I had one of those discoveries while working with a couple of kids on their rollover drops. I teach both the peel and rollover, depending on the student and which I think will work best for her. I used to teach the rollover exclusively. Now I teach more peel by far. But I still do both.

In any case, the rollover drop wasn’t quite working the way it should. It was starting too low and not breaking enough. I tried my usual explanations of what to do, but they didn’t help. Then I suggested using the wrist less and the forearm more. Suddenly it was like a lightbulb came on. By emphasizing the forearm, the hand came up higher, starting the ball around the hip, and the spin rate was greater, resulting in a flat pitch with a sharp downward break.

I don’t know if it will work for every pitcher. But it did for these two. I’ll keep using that cue — at least until someone else requires me to invent a new one.

To pitch aggressively, add a little PMS to your approach

There are some pitchers who understand inherently the need to be aggressive. No one has to tell them to get tough or be aggressive. It comes naturally to them.

Then there are those whose personalities are what you would call laid back, or even sweet. They are so nice you just want to give them a hug and tell them everything is going to be alright. I’m not sure what “everything” is, but there’s this feeling that you want to protect them from the cold, cruel world.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t help their pitching much. It’s the kind of position that requires an aggressive, almost nasty approach. So how do you explain to sweet Sue that she needs to turn into nasty Nancy in the circle?

Tonight I told one girl she needed to get a little PMS in her pitching. PMS stands for “pitching mind-set.” But it also stands for the other thing. She laughed, but understood. You need to get that mental attitude of “this is my field and you’re intruding on it with that bat.” You need to have that “take no prisoners” attitude.

That doesn’t mean over-amped. Pitchers need a certain level of inner calm to do their jobs, because it’s definitely a position that requires precision. But they also need that “killer” approach.

Talking PMS to a girl who has gone through it will make perfect sense. Tell her to get that pitching mind-set and have her go at it. Just be sure you’re ready to unleash that particular beast!

Be careful of over-reliance on video

There is definitely value in watching video of high-level players. Seeing their approach provides some good general clues as to what youth and other players should do. If you watch enough to pick up on patterns, it can even help guide more specifics.

But there is a danger in becoming over-reliant on it too. Hal Skinner made a great point about this on the Discuss Fastpitch forum. He said you have to know what you’re looking at to determine whether it’s what you should follow or not.

I want to take that a step further. Just because you see and imitate the movements doesn’t mean you’ll become a high-level player. To understand that, let’s look at it in a different context.

Suppose you could gain access to videos of Eddie van Halen, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton and Joe Satriani playing guitar. The video would be focused on their finger movements. Do you honestly believe you could learn to play guitar as well as they do simply by watching them and then trying to apply what you see? Doubtful. You might learn to play, and might even develop some pretty decent technique if you worked at it enough. But the odds are you won’t be able to play in their league. They have a level of ability hard-wired into their DNA that you can’t acquire by watching video and imitating.

The same goes with high-level softball players, or MLB hitters. There is simply more to it than that. And quite frankly, a lot of those elite players don’t have ideal (or even the greatest) mechanics. They do have an incredible level of talent that makes up for it, though.

Again, video is good and helpful. It can definitely help you find clues to success and let you know whether the path you’re following is the right way to go. But over-reliance on what you see on video may actually get in the way. Take the general principles and find the rest of the way yourself. It’s the real key to success.

Throwing inside? Check the feet

One of the common problems that crops up for pitchers is a tendency to throw inside, i.e. right handed pitcher throwing inside to a right handed hitter. While there can be any number of causes, one I’ve seen a lot is the throwing arm side getting in the way of the throwing arm. When that happens, the pitcher tends to push the ball away from that side in order to avoid hitting her hip and the ball goes inside.

If you’re seeing that, one thing to check immediately is where the pivot foot is going as she drives forward. (In case you don’t feel like thinking, the pivot foot is the foot that is on the throwing side. You’re welcome.) What you’ll probably see is that the toes of the pivot foot are going toward the toes of the stride foot after the latter lands. Often you’ll also see a walk-through, i.e. the pivot foot will keep going past the stride foot.

The simple correction is to tell the pitcher to take the toes of her pivot foot behind the heel of the stride foot. When that happens the hips stay out of the way, the arm stays on the power line, and the ball goes where it’s supposed to — usually. If nothing else it will go a lot less inside and will improve over time.

The nice thing about this instruction is it’s simple and specific. It’s not that difficult to take one foot behind the other, yet it can have a significant effect. Then all you have to do is remember to watch that the pitcher keeps doing it.

Loose elbow the key to feeling the release

Lots has been written about leading the elbow through the circle and keeping the arm loose to generate speed. But there’s another good reason to do it — high/low accuracy.

If you come through the circle with a stiff elbow, you’re going to “feel” the release being around the front leg. That will make it go high. But if you lead the elbow through the circle and keep the arm loose, you’ll feel the release closer to the back leg, and the ball will stay down.

Don’t take my word for it. Try making a circle with a stiff elbow and see where you feel your wrist snap naturally. Then loose it up and do the same. You’ll find the release point move back.