Category Archives: Pitching

In bunt situations, pitch high

I have ranted and raved on more than one occassion about the slavish devotion so many coaches seem to have to automatically sacrifice bunting anytime they get a runner on first. Besides making them very predictable, it’s also not really a high percentage play.

One thing pitchers can do to help make it an even worse idea is throw high to try and get the hitter to pop up. It works a couple of ways.

If you know the opposition’s coach is slavishly devoted to bunting the runner over, you should automatically make the first pitch either a riseball (if you have one) or an “upwardly mobile” fastball. Most hitters tend to set up too low to bunt to begin with, maybe due to practicing on low pitches off front toss or a machine. They also tend to try to bunt no matter where the pitch is, so instead of pulling back they will try to follow the pitch up. Either way, the result is often a pop-up to the catcher. If it’s a short pop-up, the catcher may be able to get the out there and fire to first to double off that runner. Easy if there is a bunt and steal on, still possible if the runner breaks but then tries to get back.

The other way it can work is for the pitcher to be aware the team may bunt, and adjust her pitch as she goes into it. In this case the pitcher starts to throw her pitch, and if she sees the batter square around she changes it to a high pitch.

My daughter Kimmie was very good at this. She could recognize even a late bunt, and would release a little late to get the ball to go high. I was watching a couple of pitchers last night in a game, one of whom is a student of mine, and they were doing the same. The other pitcher actually got one girl to pop up twice in two consecutive at bats. They didn’t get the DP, but it was close. Which meant all the coach got for her efforts was the runner still on first, and one out instead of none.

So pitchers, learn to think through the game. And if you see that bunt, or know it’s coming, go high. It just may pay off big time for you.

To gain control, you must first give up control

Ok, I know it sounds like something out of the movie Mystery Men. That’s no accident. But it really is true.

All too often, pitchers (especially beginners) will try gain control over their pitches by consciously trying to guide the ball to its intended location. The problem when they do that is they end up tensing up, and essentially guessing how to position their bodies, when to release the ball, where their hand should be pointing, etc. At that point instead of improving their control, their bodies are actually working against them and control gets worse.

To learn control, pitchers need to let their bodies relax, work on their mechanics, and let the ball go where it may for a while. In other words, instead of trying to guide the ball to a specific spot they should work on acquiring the proper mechanics to throw a ball to that location — whether they actually get it there or not. For example, when working on throwing to the glove side or throwing hand side, the focus should be on stepping slightly left or right (if that’s the method you use) and following the body with the arm circle rather than trying to “aim” the ball at the end.

Remember that control is not a goal. It is the result of doing things right. So if you really want to gain control, first give up the desire to consciously control the ball. Let go your conscious mind and let it happen organically. You’ll get where you want to go a lot faster.

A very different experience

Last night I was out teaching as usual. Only four lessons thanks to the start of the HS season, starting with an eight year old and finishing with a high schooler. During that last one Ashlee was working on her movement pitches, and broke off a particularly nasty curve ball. The curve is probably her most reliable movement pitch, and she can do wonders with it.

After throwing the pitch, a guy came walking up and asked “Wow! Was that a curve ball?” He then told me he and some of his buddies play men’s fastpitch in Wisconsin, and none of them would’ve wanted to go up against that. He also mentioned that two of the guys with him were their pitchers. Then he went back to hitting, and we finished the lesson.

After I packed up, I went by just to say goodbye to the guy (Matt) since I hadn’t had much chance to talk during the lesson. He and the two pitchers stopped what they were doing and asked what grip Ashlee was using for the curve. I showed them, at which point Matt got out his digital camera and asked if he could take pictures of that and the grips for a couple of other pitches.

One thing led to another, and before I knew it I was giving an impromptu (and free) lesson to the pitchers on how to throw a backhand changeup. We didn’t take a long time, but I did explain some of the principles and things to follow, demonstrated it (poorly I might add — I really need to do warm-ups before I start doing demos) then each of them tried it. It was rough, but they picked up the basics pretty quickly. With some work they should have a nice, new pitch come this spring.

That’s the first time I’ve ever worked with men’s fastpitch pitchers. It was definitely different. For one thing, they were both taller than me. I got the impression they were both self-taught too, mostly playing for fun.

In any case, I had a good time working with them. Maybe they’ll wander up to Grand Slam again some Wednesday night and we can talk more softball. You just never know where life — or fastpitch softball — will take you.

A feelgood week

I think every coach goes through this now and then — those days where you wonder if you’re actually doing anybody any good. You start to wonder whether everyone’s time might be better spent apart rather than together.

Then there are weeks like this one. Two significant events occured this week, both on the pitching side, that made it a real feelgood week for me.

The first was Wednesday night. I was continuing to do radar gun checks of students I hadn’t seen yet. I like to do it periodically just to get some empirical data around what I’m observing. Most kids don’t like being gunned, and in a lot of cases the results tend to be a little lower than they thought, leading to disappointment. I have no doubt that anxiety over being clocked causes them to tighten up, making disappointing results a self-fulfilling prophecy.

So it was nice when one of my students got excited to see the radar gun come out. Of course, she had her own motivation. Her dad Rick, who is a reader and contributor here, apparently had promised her a kitty if she hit 57 mph. She was psyched up to give it a go.

She came ever so close — very consistently at 55, plus one 56, but couldn’t quite get that little extra on it. Still, she had fun trying, and like all daughters she assured me that she’ll be getting said kitty anyway. Rick didn’t look so sure, and maybe he can comment on it. But we’ll probably try again in a couple of weeks. In any case, it was nice to have someone actually want to do it. And by the way, she’d gained several mph since the last time I clocked her last year so it was good all around.

Then last night my first lesson was with a girl I started with last fall. She is a sophomore who never had a pitching lesson in her life. She’d just sort of gone out there and done it. She and/or her mom decided it was time for lessons, and they knew it would be a long, tough road. The girl didn’t throw too hard or too accurately back in September, primarily due to some serious mechnical issues.

Last night, though, she was rocking the ball. Her mom told me she’d had to purchase a catcher’s mitt because her old fielder’s glove from her playing days was no longer doing the job. Her hand was getting bruised and she needed the added padding. Accuracy also was excellent — no more throwing behind the batter.

The real fun part, though, was moving to the changeup. She threw three excellent changes and I told her let’s move on, I can only screw you up from here. That got a big smile!

Both of these girls work hard, listen intently, and try their best to do what I ask them to do. They are willing to make changes in their approach, and even more importantly they are learning to correct themselves. They are aware when they’re doing something they shouldn’t, and will say something even before I can. That, to me, is the best news of all.

And that’s the beauty of coaching. They both put in the effort, and I get to enjoy it along with them. Not a bad way to spend a couple of winter nights!

Your body can lie to you

While it’s important for athletes to listen to their bodies to receive feedback on how they’re doing, it’s also possible for your body to lie to you. Specifically I’m talking about what “feels” strong and powerful versus what is strong and powerful.

Young pitchers and hitters are especially prone to this paradox. They will tense up their muscles when they go to throw or swing the bat because it feels strong. Their muscles are working hard, so they must be generating a lot of power, right?

Actually, that’s wrong. Tense or tight muscles are slow muscles, and slow muscles reduce the amount of power you can generate. Instead, you want to keep your muscles loose and relaxed so they can fire quickly and accelerate through the critical zone.

Don’t believe it? Try this.

Hold your hand up in front of your face, tense up your wrist muscles, then try to fan yourself using only the wrist muscles to move the hand as fast as you can. You won’t get much air, and if you do it long enough it will probably start to hurt.

Now relax the wrist muscles and use your forearm to make your hand move. You’ll feel a distinct breeze because your hand is moving much faster. That’s the power of loose muscles.

Another great benefit, as you may have already seen, is that loose muscles don’t tire as easily as tight ones. Loose muscles also help you keep your head from getting in the way, because the more relaxed you are the more confident you’ll feel — and the more likely you are to find a groove that makes a good motion repeatable.

The only caution is don’t equate loose with slow. You still want to be quick in your approach, attacking a pitch or swing with the intent to give it all you’ve got. Once you find the way to do both you’ll be well on your way to reaching your potential.

So while you want to listen to your body when it comes to things like pain and overuse, remember it can also lie to you. Take Frankie’s advice and relax. You’ll do much better.

The heavy ball reveals all

As I may have mentioned in the past, this year I have made overload/underload training with over- and under-weighted balls a regular part of pitching instruction. This was not a decision I came to lightly. I have used them sparingly in the past, but have been a little reluctant to go fully into them since I’d seen objections that they could lead to injury. Critics of weighted balls would say you can do the same with long toss. But since the facilities where I teach don’t really have the kind of distance required for worthwhile long toss, that wasn’t an option. Neither was going outside given that I live in the Chicago area.

I was finally convinced by two things. One was the endorsement by people such as Cheri Kempf of ClubK . Both know what they’re talking about, believe in weighted balls, and include workouts for them in their materials. The other was a summary of anarticle on injury prevention in softball pitchers that appeared in Marc’s blog. The article originally in a magazine for professional trainers, and said overload/underload training with weighted balls not only helps increase speed; it also helps prevent injury. Sold!

What I’ve come to find, though, is there is another less obvious benefit, which I call “The weighted ball reveals all.” (Hence the title of this post.)

When pitchers throw the heavier ball (it’s an 8 oz. ball, which is the most I will go over), any flaws in their technique or any letup as they throw is rewarded by seeing the ball immediately go into the dirt floor. In a previous post I talked about the upper arm being pulled down by the shoulder muscles, and the hand being pulled through release by the forearm muscles. It’s the latter where a lack of effort shows up mostly.

The added weight of the ball requires pitchers to give a little more effort to propel the ball forward. It also lets pitchers feel a letup at any point through the circle. So far I am seeing very good results not only in strength increases but improvement in technique.

It’s something to keep in mind, especially if you feel a pitcher is not accelerating through release. Again, though, I’d caution to go only 1 oz. above a normal ball, and be sure to use a lighter ball (6 oz.) to maximize the benefit.

Using the curve and screw effectively

One of the things I find fascinating when I read discussion boards is how many people — especially the old-time pitchers — seem to have a bias against the curve and the screw. Their basic premise is you should only be throwing pitches that move up or down, i.e. the rise and the drop, because they’re harder to hit than a ball that stays flat.

It makes me wonder what their expectations are or experience is with the curve and screw. I’ve found them both to be very effective pitches when thrown correctly and under the right circumstances.

First of all, the curve and screw don’t have to be flat pitches. A screw that goes up as well as in can be tough to hit (more on that later). The curve will tend to be flatter, but will still have some tendency to drop in most cases.

But the real advantage is in location. I think too often the people who don’t like the curve or screw tend to throw them or see them thrown for strikes. That’s not necessarily what you want to do.

I like a curve that starts out as a strike, out on the outer third of the plate. Then, a couple of feet before the plate it breaks off and is essentially a ball. The thing is, the hitter made her decision to swing before the ball broke, so she’s essentially swinging at a ball. If she does hit it, she likely won’t hit it very hard. But the odds are she will swing and miss, chasing a pitch that’s too far outside to hit. That’s a great 0-2 pitch. If she doesn’t go for that outside pitch, come back with a pitch on the outside corner that doesn’t break laterally. If she laid off once she’ll likely lay off again, only this time it is a strike.

If you can throw a back door curve on the other hand, you’re throwing a pitch that looks like it will plunk the hitter in the ribs. She backs off, and the ball goes across the plate for a strike. As long as the blue is watching the pitch the entire way you get an easy strike.

On the screw, there are a couple of strategies that make it effective. To simplify the description, we’ll assume a right-handed pitcher (RHP). Her pitch will break in toward a right-handed hitter and away from a lefty.

Assuming you can get actual break and not just angle, the screw can be very effective against a big hitter. It starts out looking all fat, around the middle of the plate, then breaks in on the hands. The bigger hitter who was planning on crushing the middle of the plate pitch has to pull in her hands and hit with alligator arms. If she does catch it in time, odds are you’re going to see a long foul ball down the left field line, which looks spectactular but is still a strike, same as a ball popped back into the screen.

With less talented hitters, a ball darting up and in toward their hands or face masks can be pretty intimidating. They back off, the ball stays on the plate, again you get an easy strike. One of the beauties here is that there usually aren’t many kids around who throw a good screw, so if you can the hitter has fewer reference points to use in recognizing it. If one happens to get away and plunk someone, so much the better. The others will think twice before digging in.

For lefties, the screw can be used the same as a curve for righties — a pitch that breaks off the plate. You can also have lefty slappers chasing what looks like a good pitch to slap — providing you can adjust the break point to the front of the batter’s box. Otherwise, the slapper will catch it before it breaks. Since slappers are taught to swing down, they may wind up getting the bat too low too early, swinging under the pitch because it’s not where they thought it would be. No need to throw it for a strike; it only has to look like it will be a strike when the hitter makes her decision, which is usually about halfway between the plate and the pitchers rubber.

The objective with pitching is to get hitters to swing at pitches that they thought would be good but turn out not to be. The curve and the screw can both qualify if you use them correctly.

More on the so-called natural softball pitching motion

Had this thought earlier today and just had to share.

Everyone talks about how the softball pitching motion is a “natural” motion. If that was true, parents wouldn’t pay thousands of dollars for their kids to learn how to pitch.

The reality of windmill pitching and over use injuries

Just saw this article today on the Softball Performance blog and thought it was important to pass along. In it he provides a synopsis of an article that appeared in a publication for professional trainers examining injuries in softball pitchers.

As you might expect, some of the high incidence of injury is due to poor mechanics. We’ve all seen those pitchers who are good at throwing hard despite having poor mechanics. Because they’re winning games and blowing away the competition, particularly at the younger ages, no one gives much thought to whether their mechanics are any good. Eventually, though, it catches up with them. I can personally think of a couple of kids who were phenoms at 10U and 12U, but unable to even throw a pitch by age 15.

Equally important, though, is the risk of overuse injuries in pitchers — even those with good mechanics. There is this prevailing myth that the windmill pitching motion is “safe” and “natural,” so there is little risk of injury. That’s simply not true and the article demonstrate it.

Any kind of repetitive motion, especially a violent one such as pitching, can lead to an overuse injury. Those can be tough to recover from, too. If you’re a coach and you’re throwing one girl more than three or four games in a weekend, or you’re a parent and allowing a coach to do it because “the team needs her to win,” you really need to read Marc’s post. Marc is an expert in softball-specific sports training with outstanding credentials, so when he says something is a potential issue you’d best listen.

Look at it this way: if a person get develop Carpal-Tunnel Syndrome sitting at a desk, what makes you think a softball pitcher can’t get it from pitching? I know which one I think is more strenuous.

Using the big muscles in pitching

One of the things I’ve always struggled with is finding the right way to tell pitchers how to use their bodies to throw the pitch. I’ve been describing the arm motion as pulling the elbow down or leading the elbow through the circle but that has had limited results. Some kids got it, but many others couldn’t quite seem to figure out how to do it at full speed.

A few weeks ago I was watching one of my students, a girl named Katie, during her lesson. I commented to her on how she looked like a young, much shorter Jennie Finch with the way she was using her arm. (Katie has very long arms, too, so the motion was a bit exaggerated. It also makes throwing some pitches a bit more challenging, but that’s a story for another day.)

As I observed her, I drew a mental picture of some of the videos I have or have seen of Finch pitch. That’s when it hit me — a way to describe the use of the arm and the shoulder complex that would make sure the big muscles in the shoulder become more engaged. When I watch her, Finch seems to do a better job of getting the big muscles in the back involved — probably the result of using the Finch Windmill all those years since it looks to me like those are the muscles it will work the most. When I watch in analysis mode I can almost feel the power she’s developing myself.

I tried it with Katie and got immediate results. I’ve tried it with pretty much all my students, and have seen universal results. They are able to throw harder/faster while remaining relaxed. So I thought I’d share the explanation I use now.

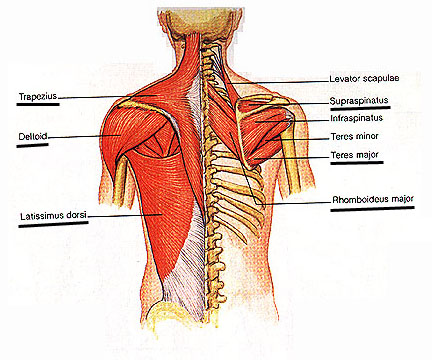

It really comes down to using or focusing on different muscle groups at different points of the pitch. I tell them when the arm is going up the front of the circle they’re using the pectoral muscles in their chest, and muscles at the top of the shoulder. (Technically that’s the supraspinatus muscle, but that’s a bit of over-explanation that causes the eyes to glaze.)

Then comes the critical part. As they start down the back side of the circle, it’s important to get the big muscles on the back side of the shoulder engaged — the deltoid, trapezius and latissimus dorsi. Sometimes I will name them, but mostly I’ll just indicate the area on the back side of the shoulder where the muscles are located. I’ve been telling them what they want to do is use those muscles to pull the upper part of the arm — from the shoulder to the elbow — down, and only that part of the arm. If they do that (as opposed to trying to pull the ball down), the elbow leads down the back side of the circle as if by magic. Finally, I tell them when the arm gets to a low point (ball is around 7:00 on a right handed pitcher, but I just show them the point) the muscles in the forearm get added on to finishing pulling the ball through to release.

Why I think this works is that most young pitchers, when they get the ball to the top of the circle, are thinking about pulling the ball to the release point. So, they engage their triceps and forearm muscles, and maybe their biceps to an extent, to do it. This motion allows them to shortcut the circle, stiffen up their arm, etc. But by separating the arm more with different sets of muscles they are able to stay loose and use a better path to bring the arm down, getting the three main pieces of the arm (upper arm, forearm, hand/wrist) to fire in sequence. It’s specific and easy to understand, which makes it easier to feel and execute.

While it may be out there, I’ve never seen the arm and shoulder action described this way before (at least that I can recall). It definitely works, though. When they do it, the pitchers can feel the added power, which puts a big smile on their faces. And ball speed definitely picks up.

Of course, this isn’t the only key to developing speed and power. That’s what makes pitching such a tough skill to learn. But it certainly helps, especially if you keep the wrist loose and ball pointed away instead of down on the back side of the circle. Give it a try and let me know how it works out for you.