Author Archives: Ken Krause

The Downside of Being a Multi-Sport Athlete

There are many benefits to being a multi-sport athlete, as has been detailed here as well as in numerous articles and athlete-driven promos across the Internet. The cross-training, the different styles of coaching, the different atmospheres, etc. all contribute to making a well-rounded athlete who can compete more effectively.

The old-school types in particular love to talk about all the great things that come with participating in multiple sports, and how they did it and it made them better all the way around.

But there’s a very definite downside in today’s world, especially if you want to compete at a high level. The downside is the time commitment required and its effect on the athlete’s physical and mental state.

You see, back in the “good old days” of multi-sport athletes each sport had a season. You played volleyball or ran cross country or did whatever in the fall. When that season was over it closed out and the athlete moved on to basketball or swimming or whatever in the winter. Then came softball or track or another sport, which was separated from everything else.

Today, however, every sport seems to be 24 x 7 x 365. A typical day will see an athlete attend a game for a school sport in one season as well as a practice for another sport that is out of season. Throw in lessons, speed and agility sessions, weightlifting classes – not to mention school/homework and possibly work for the older players – and it’s amazing these players can stand upright much less participate in so many activities.

In the summer they don’t have school to contend with, but often they have two or even three full-blown teams in different sports running at once along with the other activities. No rest for the wicked, eh?

What it often means is athletes who are never 100% healthy or energized. Instead, they are doing the best they can each day, but not necessarily the best they’re capable of.

What’s the solution? The ideal situation would be setting up a system where the governing bodies of various sports get together to set priorities.

Each sport would have a full-on season where they take the bulk of the time, while the others step back to a very limited level. For example, in the summer softball would have priority, and sports like basketball and volleyball would hold no tournaments on the weekends and perhaps be limited to a single practice each week. In fall a different sport would have priority and summer sports would be limited in the same way.

Of course, that’s never going to happen. The sports culture here in America is too tied to winning for any sport to take a back seat to others, even if it’s for the benefit of the athletes themselves.

The next best alternative is for parents to keep an eye on their athletes and set the priorities for them. Even if it makes them unhappy.

They and their athletes should figure out which sport is their priority and make that the focus of their efforts. They should then, in my opinion, treat any other sports as fill-ins.

Rather than playing club/travel for every sport, play it for one and then do the others for school or at a rec level.

Club/travel coaches can also help out by voluntarily limiting practices to once a week when out of season, with liberal policies if their players have to miss due to a conflict with the main sport.

This plan may not solve everything, but it’s a start.

The level of commitment required these days is just insane in my opinion. It’s time to change the culture.

We need to make it possible for athletes to receive the benefits of being multi-sport athletes without the detrimental effects. It will be better for them, better for their parents, and ultimately better for their teams too.

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio on Pexels.com

What to Expect When You Become a Pitcher’s Parent

Sooooo…your daughter has decided that she wants to become a pitcher.

Congratulations to her! That’s a big step, especially given the importance of the position in fastpitch softball.

The value of a quality pitcher in softball is roughly the same as the value of a quality quarterback in football. While those roles differ, both can have a huge impact on whether the team wins or loses.

Because of all of that you are excited. You can’t wait to watch your wonderful, softball-loving daughter shine in the circle and feel the glow of admiration from coaches, teammates, and fans alike.

I know. I’ve been there – twice – and have seen those feelings in the eyes and body language of countless students.

But it’s not all sunshine and unicorns, even if your daughter is a tremendous athlete and a start in other aspects of the sport. So now that that decision has been made, let me clue you newbies in on what you’re in for going forward.

Parents of pitchers, current and past, be sure to chime in down in the comments about any aspects I’ve missed. It’s been a while for me.

The Time

You know that thing they call free time? Forget about it for the next 10-15 years, depending on how old your daughter is.

Because it’s a thing of the past.

Becoming even a decent pitcher takes a lot of work, i.e., many hours spent honing the craft. So while other parents gets to unwind at the end of a long, tough work day by collapsing on the couch, perhaps with an adult beverage or two, there is no such paradise waiting for you.

Instead, you will come home, change, maybe grab a quick bite, and then head out to a field, facility, and/or lesson so your daughter can get better. You see, pitching mechanics require a tremendous degree of precision and coordination to execute, and even the slightest variance can mean more walks than strikeouts, or too many hit-by-pitches, or too many balls left too fat in the zone resulting in big hits.

Not to mention there’s always another mile per hour or two to chase. So your “free time” will be spent sitting on a bucket and/or driving somewhere so your daughter has her best chance of succeeding.

The Nerves

Ever see a crowd sitting calmly watching a softball game? Everyone there is relaxed, chatting about the game or their lives, checking their phones for messages, maybe enjoying a snack or two on a lovely evening.

What you won’t see there is the current pitcher’s parent(s). That because the parent(s) are frantically pacing up and down the sidelines, or more likely somewhere behind the outfield fence, living and dying on every pitch.

Remember how I said in the beginning it’s a huge responsibility? As a pitcher’s parent you’re going to feel all the weight of that responsibility, probably much more than your daughter does, and you’re not going to be able to do a danged thing about it.

Except pace. And mumble to yourself. And question every pitch call from your coach as well as the umpire. Then pace some more.

You are basically trapped in a hell of your own making while you try to will your daughter to hit her spots, make the ball spin, or throw as hard in a game as she does in practice.

Eventually she will get there. But then you’ll just stalk up and down the sidelines or outfield fence and fret about the outcome of every pitch anyway. Because that’s what pitcher’s parents do.

The Fighting with Your Daughter

Learning to pitch is a long, arduous process with many ups and downs. As a good parent you want to see your daughter succeed.

Unfortunately, she may not realize how much work it takes, and thus will want to live the same type of life as other girls her age. As if!

So the two of you will fight about whether she can go here or there, or whether she needs to practice first.

You will also fight about mechanics. Because you heard one thing at her last lesson and she heard another. Or you’ve been checking the Internet for advice again and want her to try whatever tip or trick you just learned.

You will fight about what happened during the game. Did she try hard enough? Did she give up too many walks? Why did she throw a changeup to a hitter who clearly couldn’t hit her faster pitches? Why didn’t she throw home to force the runner there instead of throwing to first base and letting the run score?

And so on, and so on.

Fathers and daughters in particular will fight, because that’s just natural in human dynamics. The good new is, as tough as it can be, better to be fighting about pitching than who she was with or what she was doing last night.

Oh, and if you are also her team coach as well as practice catcher, get ready for many storm clouds ahead. It’s gonna be a rough ride.

The Money

So, you thought softball was expensive before your daughter declared she wanted to be a pitcher? Those will quickly become the good old days.

It starts with lessons of course. They aren’t cheap, and they have to be done frequently to get anywhere. Like once a week or once every other week (for a longer period of time) if you want her to gain competence quickly.

You will also need the ubiquitous bucket to carry balls and a glove in, as well as to sit on during lessons (hence the term “bucket dad” or “bucket mom”). It’s not required, but unless you’re a former catcher or someone who does a lot of squats normally you’re probably going to appreciate it quickly.

Then, as your little pitcher gets better, you’re going to start needing to purchase special equipment. It starts with a catcher’s mitt because your hand can’t take it when she starts popping the glove.

Then, as she learns to throw changeups and drops, you’ll probably want a pair of shin guards, and maybe a paid of shoes with steel toes. As speed picks up and movement gets sharper, you’ll probably need a catcher’s helmet too, so at that point you may as well get a chest protector as well.

As she gets better she will be sought after by better teams that play more often and travel farther to do it. Now you’re looking at thousands more dollars for the summer alone.

Eventually what started out as a nice little diversion ends up costing as much as a decent boat. But that’s ok, because you won’t have time to enjoy a boat even if you bought one.

The Heartbreak

It’s hard to watch your child struggle at anything, much less fail. But softball is a game built on failure, and nowhere is it more painful than when your daughter is having a tough time pitching.

Sure, it’s hard to watch your daughter strike out too. But that probably only happens maybe two or three times a game. But if she’s throwing balls and hitting batters when she should be throwing strikes, or serving up meatballs like she’s working at Olive Garden, it can be devastating to her – and to you.

Basically, a pitcher’s parent tends to live and die on every pitch. Especially during a tight game or one against a major rival.

So you may find yourself dying dozens of times during a game, and even a hundred or more on the weekend. And that’s just you.

Seeing the pain on her face during or after the game is tough to take. Yet you’re probably going to have to live with that pain for a while until she gets more experienced. If you’re not ready it can come as quite a shock.

Worth It?

So yes, the struggle is real. Which begs the question, “Is it worth it?”

That’s a decision you’ll ultimately have to make. Maybe your daughter will try it, realize how hard it is (and/or how much work it really takes) and opt out.

That’s ok. The team needs a center fielder too.

But if it’s something she really wants to pursue, in my opinion the answer is yes. Because she will learn how to overcome obstacles galore and the two of you will spend plenty of quality time together (when you’re not arguing). Probably much more than you would have otherwise.

Not to mention there’s nothing like the joy in your daughter’s face when she strikes out her first batter, retires the side in a close game, pitches her to team to a championship, and earns an MVP medal or game ball for her outstanding performance.

So if one day your daughter announces that she would like to be a pitcher, it’s ok to celebrate. But be aware of what you’re getting into and strap yourself in.

Because it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

5 Reasons Lefties Should Be Trying to Hit to Right

The other day I was working with a left-handed hitter and noticed two things.

The first was that her sister, who went out to shag balls after her own lesson, set herself up in left field. The second was that the sister was correct – everything was going out that way.

I told the girl who was hitting that she was late, needed to get her front foot down earlier to be on time, especially on inside pitches, and all the usual advice for someone who is behind the ball. But then it occurred to me – she might have been going that way on purpose.

So I did the most sensible thing I could – I asked her about it. “Did someone tell you to hit to left all the time?” I asked.

“Yes,” she replied. “My old team coach.”

This is the second time I’ve heard that from a lefty. The first actually got that advice from a supposed hitting coach.

Forcing lefties to try to hit to left on every pitch makes no sense to me. Sure, if the pitch is outside you should go with it. That’s hitting 101.

But on a middle-in pitch? No way! Here are five reasons why that’s just plain old bad advice.

Giving Up Power

This is the most obvious reason. The power alley for any hitter is to their pull side.

You get the most body and bat velocity on an inside pitch when you pull it. Laying back on an inside pitch to try to hit it to left is taking the bat out of the hitter’s hands, which you don’t want to do – especially in today’s power-driven game.

Encouraging the hitter to barrel up on the ball and hit to her pull side will result in bigger, better, more productive contacts. And a much higher slugging (SLG) and on base plus slugging (OPS) percentage, leading to more runs scored and opportunities taken advantage of.

Creating a Longer Throw from the Corner

If a left-handed hitter pulls the ball deep down the first base line and has any speed at all there’s a pretty good chance she will end up with a triple. It’s a long throw from that corner to third base, and will likely actually involve two long throws – one from the corner to the second base relay, and another from the relay to third.

A hit to the left field corner, however, will more likely result in a double. It’s a much shorter throw and one that doesn’t (or at least shouldn’t except for the younger levels) involve a relay. One less throw means one less chance for something to go wrong for the defense.

I don’t know about you, but I’d much rather have my runner on third than on second. As this chart from 6-4-3 Charts shows, your odds of scoring go up considerably regardless of the number of outs when your baserunner is on third:

You probably didn’t need a chart to show you that – it’s pretty easy to figure out on your own – but it always helps to have evidence.

Hitting Behind the Runner

Coaches spend a lot of time talking screaming at their right-handed hitters about the need to learn how to hit behind the runner at first. Then why shouldn’t lefties be encouraged to do it as well?

It ought to come natural to a lefty. Now, part of the reason for hitting behind the runner is to take advantage of a second baseman covering second on a steal, which is less common in softball and probably doesn’t happen with a lefty at the plate.

But what about advancing a speedy runner from first to third? Again, longer throw from right.

A well-hit ball to right, even one that doesn’t find a gap, gives that speedy runner a chance to get from first to third with one hit. A well-hit ball to left that doesn’t find a gap will probably still require the runner to hold up at second because the ball is in front of her.

So if you’re teaching your lefties to go to left all the time you’re leaving more potential scoring opportunities on the table. In a tight game, the ability to go to right instead of left could mean the difference between a W and an L.

Taking Advantage of a (Potentially) Weaker Fielder

This isn’t always the case. There are plenty of great right fielders, especially on higher-level teams.

But for many teams, right field is where they try to hide the player who may have a great bat but a so-so ability to track a fly ball or field a ground ball cleanly.

Why hit to the defense’s strength when you can hit to its weakness instead? At worst, if right field is a great fielder you’re probably at a break-even point.

If she’s not, however, you can take advantage of the softball maxim that the ball will always find the fielder a team is trying to hide.

Reducing Their Chances of Being Recruited

Most of today’s college coaches want/expect their hitters to be able to hit for power. Not just in the traditional cleanup or 3-4-5 spots but all the way through the lineup.

A lefty who only hits to left looks like a weak hitter. (And is, in fact, a weak hitter.)

Unless that lefty is also a can’t-miss shortstop, college coaches are going to tend to pass on position players who don’t look like they can get around on a pitch. That’s just reality.

Teach your lefties to pull the ball when it’s appropriate and they stand a much better chance of grabbing a college coach’s attention. And keeping it until signing day.

Don’t. Just Don’t

Teaching lefties to hit to left as their default is bad for them and bad for the team. It also doesn’t make much logical sense.

Encourage them to pull the ball to right when it’s pitched middle-in and you -and they – will have much greater success.

The First Rule of Changeups

Whether you have seen the movie or not, I think most people have heard that the first rule of Fight Club is that you never talk about fight club.

This quote came to mind a few days ago while I was working with a new student on developing her changeup. As I watched her it hit me: the first rule of changeups is that they can never LOOK like changeups – at least until you release the ball. After that, they’d better!

What do I mean by they can never look like changeups? Basically, you don’t want to have to do anything with your approach, your body, or anything else to make a changeup work.

The changeup should always look like it’s going to be a fastball until the ball is on its way, when suddenly the hitter realizes (hopefully too late) that the pitch they thought was coming is not the pitch that’s actually coming.

Yet people teach crazy and self-defeating stuff about the changeup all the time. So to help those of you who are just getting into it, here are some things you definitely don’t want or need to do to make a changeup work.

Using Strange Grips

This is something I see all the time. I’ll ask a new student who says she throws a changeup to show it to me, and the first thing she does is start tucking a knuckle or two, or go into a “circle change” grip where you hold the ball with the middle through little fingers while the thumb and first finger make a circle.

All of that is not only unnecessary but it’s actually counter-productive. What makes a changeup work is that it surprises the hitter.

If you go into some crazy grip that is easily spotted from the coaching box, or worse yet from the batter’s box, the only surprise that’s going to happen is you being surprised at how quickly that pitch leaves the ballpark.

If you really want to disguise the change you should be able to use your fastball grip to throw the changeup. Because, and I will say it loud for the people in the back, it’s not the grip that makes a pitch work; it’s how the pitch is thrown.

If you have a well-designed changeup you’ll be able to use your fastball grip, maybe with a slight modification such as sliding the thumb over a little, and still take the right amount of speed off.

Slowing Down Your Arm or Body

This is another one that is pretty obvious to the hitter, the coaching staff, the players on the bench, and even people just cutting through the park to get to the pickleball courts.

If you have to slow your arm down to throw a changeup, you’re not throwing a changeup. You’re throwing a weak fastball.

Think of a changeup as being the polar opposite of most people’s experiences hitting off a pitching machine fed by a human. The human slowly brings the ball down to the chute to put it in, maybe fumbles with it a bit, then the ball shoots out at 65 mph or whatever speed the coach thinks will help hitters hit better. (Spoiler alert: setting the machine too high actually hurts your hitters.)

The reason machines are so hard to hit off of is that the visual cues of the arm don’t match the speed of the pitch. Because if you actually threw the ball with that arm motion it would go about three feet away at a speed of 5 mph.

A great changeup turns that model on its head. The arm and body speed indicate a pitch coming in at whatever the pitcher’s top speed has been.

But because of the way it’s released, the ball itself actually comes out much slower. The mismatch between the arm speed and ball speed upset the hitter’s timing and either gets her to swing way too early (and perhaps screw herself into the ground) or freezes her in place while her brain tries to figure out the discrepancy,

Either way, the hitter is left wondering what happened – and now has something new to worry about at the plate because she doesn’t want to be fooled again.

Making a Face or Changing Body Language

This is something that often happens prior to the pitch.

Maybe the pitcher has developed a habit of sticking her tongue out before she throws a change. Maybe she changes where she stands on the pitching rubber or does a different glove snap or alters their windup or has some other little “cheat” that helps her throw the pitch.

All of these things can send a SnapChat to the hitter that a changeup is about to happen.

Smart pitchers will video themselves throwing fastballs and changeups , especially in-game, to see if anything they’re doing is giving away the pitch that’s about to be thrown. If there isn’t, great.

But if there is, they need to work at it until they’re not giving it away anymore. The pitcher’s chief weapon when throwing a changeup is the element of surprise.

They need to make sure they’re maintaining it until the ball is actually on its way.

Keep the Secret

A changeup that everyone knows is coming is not going to be very effective. And given today’s hot bats it can be downright dangerous for the pitcher.

Remember that the first rule of throwing a changeup is that it can’t look like you’re going to throw a changeup and y

The Essence of Being a Great Teammate

There have been tons of books and articles written instructing players on how to be a great teammate. Many of them talk about things like cheering loudly in the dugout or communicating well or standing up for a teammate if he/she is verbally or even physically attacked.

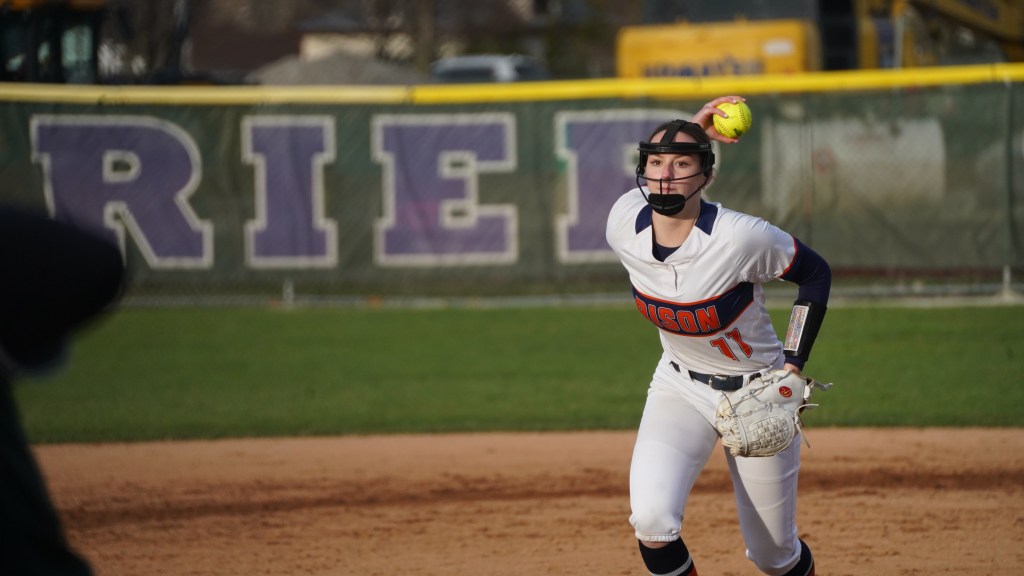

But one of the best things you can do is to simply step up and do something that needs to be done to help the team – even if it’s outside your normal role. I recently heard a great example involving one of my pitching students, a young lady named Sammie.

Sammie’s high school team was scheduled to play a game that day. They typically have just enough to actually play, so when they discovered that their one and only catcher had gone home sick from school it left a giant hole in the lineup someone had to fill.

I’m sure you can see where this is headed: Sammie said she would volunteer.

Now, as I understand it Sammie has never caught before in her life. Not even in rec ball.

She has always been a pitcher, and she has become an excellent pitcher. But she had pitched the day before while fighting through an injury so her pitching again wasn’t a possibility.

She could have just stood by and looked the other way, but the team needed someone and she said she’d strap on the gear and give it a shot.

That’s remarkable enough. But there’s one other minor factor that makes it even better.

If you look at the photo at the top of this blog post what do you see? Look closer. There you have it.

No, that photo isn’t reversed. Sammie is a lefty.

So basically you have a lefty who has never played the position before stepping up to play one of the toughest and most important positions on the field. And one with some extra risk of getting hurt through foul tips or chasing after pop-ups or plays at the plate or just flat-out missing the ball because you’re not used to catching it while someone is swinging.

In my world, that’s the essence of being a great teammate. Because if Sammie doesn’t step up (and clearly no one else plans to either) the team doesn’t play.

There are many ways players can contribute to a team. But when you’re willing to look beyond your own needs and worries and do something that’s well outside your comfort zone you separate yourself from the crowd.

Or as Mr. Spock would say:

The Run Rule – and the Golden Rule

Most of us are taught the Golden Rule as children: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

So you have to wonder what goes through some coaches’ heads when their team is clearly going to run rule their opponents but they decide to keep their foot on the offensive accelerator anyway. I mean, why would you beat an opponent by 15 runs when you could do it by 30 runs instead? Right?

This topic came up when I was talking to a coach friend of mine who recently saw this type of beating in real time. She wondered why the coach of the superior team felt the need to run up the score when the game was already decided pretty early.

I didn’t have an answer. Maybe the winning coach wasn’t used to being in that situation and didn’t know how to control events on the field.

Maybe she thought that hanging a big number on their opponents would somehow give her team more confidence and they’d start playing better. Maybe she just didn’t know any better.

Maybe the losing team over-reached (or under-researched) when entering that tournament or scheduling that game and put themselves in a bad situation.

Or maybe, just maybe, the winning coach enjoyed the feeling of beating up on a weaker team. There are people like that out there.

Whatever the reason, scores of big numbers to 0 or 1 really shouldn’t happen. Once the direction of the game has been established as being greatly lopsided, the coach of the team on top should do what he/she can to keep it under control rather than humiliating a group of kids who may not have been playing for very long or just don’t have the talent to compete at that particular level.

There are several ways the superior team can help keep the score from getting out of hand:

- One of the first things to do is quit stealing bases. Not just actual steals but even on passed balls or wild pitches, and especially with a runner on third. Just hold the runners where they are to give the fielding team more of an opportunity to make plays without the offensive team racking up runs.

- You can also have baserunners run station-to-station. In other words, even though runners could move up two or three bases at a time, just have them move up to the next base and stop. And no taking an extra base on an overthrow. I can already hear the objections: “But I want to teach my runners to be aggressive and this will hurt that plan.” Stop already with that. First of all, the head coach can (quietly) explain what the team is doing (and why), letting the team know it’s only for this one game. And if pulling up in one game really leads baserunners to be unaggressive in the next game, well, the coach has some more work to do on teaching the game.

- You can have runners slow down a little to give fielders a little extra time to make a play. Not too much – you don’t want to look like you’re trying to show up the other team. But a little bit might help.

- If those steps don’t help, the team on offense can start making outs on purpose. One of the classic strategies is to have baserunners leave the base early so they can be called out by the umpire. In my experience it’s best to let the umpire know quietly you’re planning to do it so they are watching for it.

- Another way is to have hitters line up at one of the edges of the box and then step out as they hit. For example, a hitter who strides can have her front foot at the front of the batter’s box and stride out. A slapper can run out of the box and slap or bunt. Again, it helps to let the umpire know you’re doing it to make it easier for him/her to call.

- On a ground ball, baserunners can gently run into fielders to be called for interference rather than going around. It should be just enough to be seen, but definitely not enough to cause distress or injury.

- And, of course, for teams that have designated starters and subs, put those subs in early. The starters might appreciate the break and the subs will have a chance to play. Just make sure the starters know it’s now their turn to support their teammates on the field and at the plate. The risk here is that the subs will be anxious to show what they can do and might bring a little too much enthusiasm to the opportunity. So make sure everyone on your side understands what’s happening and what they are expected to do.

There are also a couple of ways I wouldn’t go about it, including:

- Telling a hitter to strike out on purpose, or just go for a weak hit. While the intention may be good, you run the risk of having that come back to bite you in a game where you do need a hit.

- Having players bat opposite-handed. Again, while the intention might be good, it could also be viewed as trying to show up the other team. They feel bad enough. No use adding insult to injury.

- Having all your hitters bunt. Most teams spend less time on their bunt defense than their standard ground ball defense. This is especially true of weak teams in my experience. While you may think you’re helping them, you could be making them look even worse.

Coaches should want to keep the score somewhat under control because it’s the right thing to do. Again, the Golden Rule.

You wouldn’t want someone running the score up on your team, so don’t do it to someone else. But there’s another reason too.

You may have also heard the phrase “Karma (or payback) is a b***h.”

Some day that team you’re humiliating today might get better while yours loses a step or two.

Coaches tend to have long memories for these sorts of things, so should that day come what you do today could have a big impact on how you end up looking and feeling then.

No one learns anything when a team runs up the score on a weaker opponent. Except that maybe someone doesn’t have much class.

“Do unto others” and you can never go wrong. The lessons learned there will be worth a lot more than a few extra runs in the “runs for” column.

No Virginia; Data and Stats Aren’t “Ruining” the Game

One of the most popular complaints heard these days about both fastpitch softball and baseball these days is that all the attention being paid to data and statistical information is “ruining” the game. Old-timers (or Traditionalists as we’ll call them since they’re not always old and older coaches are often the first to adopt new breakthroughs) in particular long for the days when decisions were made based on experience and gut instinct alone.

Well, the problem with that is a whole lot fewer people actually have great gut instincts than think they do.

And to be honest, experience is really just data/statistics stored in a different way.

The reality is data and statistics can be extremely helpful in developing players as well as making in-game decisions. Let’s look at a few cases where understanding the data and statistics can be a difference-maker.

Setting up batting orders

Traditionalists believe they know who the good hitters are. And barring something crazy they will tend to build their lineups based on those beliefs, even when that approach clearly isn’t working.

Those who use data and statistics on a regular basis will take a look at who is actually hitting well in games – especially who has a hot hand right now – and try to give those players more at bats. It might not always work out, e.g., a hitter who does well in the relatively low pressure 6 spot might struggle more at 2 or 3.

But if certain players are out-hitting others, even if they don’t look like they should be, it’s definitely worth finding out if a lineup shakeup might produce a few more runs.

Using pitchers more effectively

While there are still plenty of old-school coaches out there who think they can ride one arm to a championship, in reality that has become much more difficult to do. Better training for hitters, and quite frankly more exposure to quality pitchers, means seeing the same pitcher three or four times is often an advantage for the offense late in the game.

With data and statistics coaches can see not only which starter matches up best with a particular team but which relievers seem to be most effective following those starters.

For example, say you have a fireballing lefty start the game. She does great a couple of times through the lineup, but then the offense seems to have figured her out.

Who do you put in now? Your next best Ace or perhaps more of an offspeed/spin pitcher? With data at your disposal you can see how well opposing teams have hit each so far after pulling the starter.

While there are no guarantees it will work again, you’ll at least have a starting point for making the decision. You might also use the information to assign specific roles to pitchers, such as middle reliever or closer, based on their effectiveness in different parts of the game – just like baseball does.

By seeing who performs well when you can manage your staff to ensure you’re making the most informed decisions you can while also perhaps saving your best arms for when they’re needed most.

Dealing with defensive shifts

This is probably one of the most-hated aspects of data and statistics, and the one that draws the most complaints. Seeing three infielders stacked up on the right side, or an infielder in an outfieldish position because statistically that’s where a particular hitter normally hits, is believed to be an abomination on the game.

Why? Because your hitter can’t do what he/she normally does and get away with it? Too bad.

Any type of unusual shift is going to create a glaring weakness. A smart offense coach (or player) will take advantage of it. A stubborn one will get burned by it.

I remember watching a Major League Baseball game a few years ago where the defense shifted to the right side, leaving the third baseman roughly between second and third. The hitter took some big cuts and eventually grounded out to one of those fielders on the right side.

I couldn’t understand why that hitter didn’t just bunt the ball down the third base line. He could have walked to first.

I get that contracts may be structured for extra base hits and all that, but the core idea of baseball/softball is get on base, then get to the next base until you make it back home. Laying down a bunt where no one can get to it will accomplish that.

It will also make the defense eventually reconsider the wisdom of those special shifts, so problem solved.

Selecting a pinch hitter

Pinch hitting is a tough role. You’re basically sitting and watching the game with little pressure until a critical situation comes up.

Then you’re put in under maximum pressure. It’s not for everyone, and even great hitters can crumble under those circumstances.

With data and statistics, however, you can see who performs well under pressure – including which bench players do the best job of producing quality at-bats when called on. They’re not necessarily the ones with the highest overall batting average, but they are the ones who are best prepared for the specific circumstances you’re facing.

Having that information at your disposal can help guide you to a better decision. One that is based in fact rather than emotion.

Developing players

Data and statistics aren’t just valuable for in-game decision-making. They can also be tremendously helpful when you’re trying to improve players in practice or lessons.

A good example is helping pitchers learn how to spin their pitches. Tools such as Rapsodo or the DK ball can measure spin rates and spin directions to help pitchers learn the techniques that will lead to late break on the ball.

A radar unit, particularly one that is running constantly, can help pitchers see whether they are progressing while also holding them accountable to give maximum effort throughout the session.

The same radar unit can measure bat speed and ball exit velocity to determine if a hitter is progressing. Sensors such as Blast Motion that attach to the bat can provide even more data about bat position, launch angles, etc. that can help hitters hone their craft.

And complete systems such as 4D Motion can really get “under the hood” to show whether the way a player is moving is optimal in order to make deeper corrections that can have a profound effect on success.

These and other measurements use proven science to help players optimize their approach to a variety of skills that will help them perform better in the field – without all the guesswork and opinions that often hamper training.

Valuable tools

Does that mean data and statistics are a panacea that means coaches no longer have to know what they’re doing to succeed? Of course not.

The most important aspect of coaching remains the ability to relate to players and get the best out of them.

But data and statistics are great tools that help coaches see what they need to see they can focus on the areas that will deliver the best return on investment in every player. The coaches who embrace them, and learn what they really mean, will gain a tremendous advantage over those who still just want to rely on gut instinct.

In my opinion it’s definitely worth the time and effort.

Photo by ThisIsEngineering on Pexels.com

Relentless Competitors: Nature or Nurture?

Today’s post was inspired by a Facebook post from my friend and fellow pitching coach James Clark. James is the owner and chief instructor of United Pitching Academy in Centerville, Indiana and is very familiar with what it takes to build champions.

His original question was:

“Being competitive and having an absolute desire to win. Is this a personality trait or can it be coached?”

He and I chatted about it a bit ourselves and I will share some of his thoughts shortly. But you have to admit it’s a great question – especially since it generated a lot of comments on both sides of the issue. First, though, my thoughts.

In my experience it’s kind of a mix of both. Some people come by their competitiveness and relentless desire to win naturally.

On the positive side, these are the types of players who will spend extra hours taking ground balls or spinning pitches from close distance or getting in extra batting practice or hitting the weight room. During games they keep a positive attitude and do their best to lift their teammates, even when their team is down a bunch of runs, because they just can’t fathom losing without doing everything they can to win.

(On the negative side, these are also the players who will play through injuries when they should be taking time to heal themselves, and sometimes can be harsh on teammates they don’t think are giving the same level of effort.)

You don’t really have to do anything to push these players to give their all. They know no other way to approach the game.

It’s like the story about football legend Lou Holtz being asked how he became such a great motivator of players. “I find the players who are self-motivated and cut everyone else,” he said.

Those players stand out, however, precisely because they are so rare. For the rest, having that type of indomitable spirit and high level of competitiveness is something that has to be nurtured.

Especially in female athletes, because even today, in 2023, society doesn’t really value those traits in females as much as they do in males. Just look at the controversy over the NCAA women’s D1 basketball championship where a simple taunting gesture – one that would probably hardly raise an eyebrow on the men’s side – became a national scandal.

James and I both agree that competitiveness is hard-baked into our DNA at some level as part of our survival mechanism. As he put it:

“The natural selection idea stems from prehistoric/caveman times. You had to compete with nature to survive. Failure to do this was certain death.

“Needing to hunt and kill your next meal fostered the sense of survival. In modern times we tend to use sports to feed this primal instinct.. If it’s not fostered within a culture where leadership is promoting this “succeed or fail to survive mentality it eventually goes away.”

I agree with that thought. At one point in our early existence it was kill or be killed. Our primitive reptile brains still retain that somewhere.

But I also believe once humans began organizing themselves into societies they were able to distribute workloads based on ability. Those who were inclined to hunt would hunt, while those who were inclined to farm would farm.

The farmers might still compete for who could grow the most food or the largest pumpkins, and could defend themselves if they had to. But they were largely relieved of the “kill or be killed out of necessity” aspect of life and so perhaps didn’t have that same urgency.

Which brings us to today with sports. For some, it’s definitely a way of life, which means winning and losing is uber-important to them.

Winning brings satisfaction while losing brings literal pain and suffering. (You would think winning would bring delight but I think for most uber-competitors the joy is short-lived because there’s always another hill to conquer.)

For others, winning is less life-and-death. Sure, everyone wants to win, but for this group it’s not so life-and-death. And there’s always a segment of the population that’s just content to play whether they win or lose.

Which means coaches will need to bring that long-buried competitive streak out in those players. They will need to inspire those players to pursue winning at a deeper level than they may have on their own.

A big part of that is establishing a culture where winning is an important goal. Players have to have a big desire to win before they will go out of their way to compete better.

Finding a “lead goat” or two who can help drive the others is important. Take the natural competitors and make their enthusiasm infectious.

The belief that “we can do this” has taken many teams from the cellar to the penthouse and inspired players to do things they never thought they could (or would) do.

In my opinion, and I think James would agree, it’s one of the greatest gifts a coach can give his or her players. Because learning how to compete and succeed in sports is a skill that can be easily transferred to other aspects in a person’s life. Because everything in life is a competition at some level, so the sooner you learn how to compete, and build a burning desire to win, the better prepared you will be for life’s larger challenges.

In many cases, when you have a natural relentless competitor the best things the coach can do is guide them in how to direct that energy, give them the tools to pursue their passion, and then stay out of their way.

For everyone else, that’s where the real coaching comes in. It’s not just about X’s and O’s, or mechanics or strategies. It’s about lighting that spark that may be buried deep inside of them to help them exceed their current expectations in order to become the players they’re meant to be.

Make a commitment to be that spark.