Category Archives: Coaching

Coaches, Stop Putting Pitchers in Games without Warming Them Up

Today’s post was a suggestion from several of my pitching coach colleagues who all shared similar horror stories. As you can probably tell from the title, it comes from their pitching students being put into game situations (usually very difficult ones) without the opportunity for a proper warm-up.

If you’ve been seeing this rest assured you’re not alone. Apparently it’s happening all over the softball world based on the stories I’ve been hearing, and expect to hear in the comments afterward.

Now, let me state up-front that I don’t think too many coaches are doing it intentionally. It’s more a matter of circumstances.

Here’s a typical example. Pitcher A starts the game and is doing fine for three inning. Then, in the fourth, the other team figures her out and starts hitting her, or she starts walking batters like she’s being paid to do it, or a combination of both.

Suddenly the coach realizes he/she needs to bring in a reliever and calls in Pitcher B from first base, or right field, or the bench, or wherever Pitcher B has been spending her time this game. No warning, no warm-ups, just her name called and a frantic gesture to come to the circle.

Of course, Pitcher B isn’t at all ready to come in and pitch effectively, either physically or mentally, so she throws her five allotted warm-up pitches and then proceeds to struggle. In the meantime, the coach gets mad because Pitcher B is not performing up to her usual standards; doubly mad if Pitcher B is normally his/her reliable Ace.

It happens. I’ve seen it happen. I’ve counseled distraught pitchers after it happened, because they feel like they let their teams down, their coaches yelled at them for not pitching their usual games, and in some cases they’ve now lost confidence in their ability to pitch at all.

But the problem isn’t with the pitcher. It’s with the coach who didn’t plan ahead and perhaps doesn’t understand that going in to pitch is a little different than subbing in at second base or shortstop or center field.

There is a reason pitchers typically warm up for anywhere from 10 to 40 minutes or more. Pitching a softball well requires a complex set of movements that are unique to that position and that must be precisely timed.

A little stiffness here, a little imbalance there, and the whole mechanism is off enough to cause pitchers to struggle. It doesn’t take much. It also requires a certain rhythm that must be found before the pitcher is ready to go full-out. And that’s just for a basic fastball.

Each pitch also needs its own warm-up time to help the pitcher home in on the precise mechanics that will make it do what it’s supposed to do, whether it’s to move in a certain direction, give the impression it will come in at a different speed, or do something else that will cause the batter to either swing and miss or hit the ball weakly.

On top of all that, pitchers need that warm-up time to prepare themselves mentally for the battles ahead. They need to find their inner calm or inner fire or whatever it is they use to help them compete, and they need to feel ready to face the trial by fire that is inherent in the position.

None of that will happen if the pitcher is suddenly yanked into the game and given five warm-ups. It also won’t happen if a pitcher is pulled from the game or the bench and told to go warm up quickly and then two minutes later the coach is asking “Are you ready yet?”

Oh, but you say, the pitcher warmed up before the game. I guess that’s better than nothing, but just barely. Keep in mind that that warm-up likely happened more than an hour ago.

In the ensuing time most if not all of the benefits of warming up have been lost. The pitcher’s motion is cold (even if the arm isn’t), her rhythm has been lost, and her mind has been focused elsewhere.

It’s almost the same as saying she warmed up before the game yesterday so should be ready today. In pitching terms, that hour is so long ago it’s as if it never happened.

I understand that there are times when it’s unavoidable. Sometimes the pitcher gets injured, whether it’s taking a line drive off the bat, having a runner slide into her on a play at the plate, getting hit by a wild pitch when she’s batting, or twisting her ankle landing halfway into a hole that resulted from no one dragging or raking the field after the first of the day was thrown.

At that point someone has to take over. In these types of emergency scenarios it’s important for coaches to keep their expectations (and their game plans) realistic.

Keep pitching calling simple (fastballs and changeups most likely) and don’t be surprised or express disappointment or anger if the pitcher isn’t as effective as she usually is. She’s trying, coach.

In any other situation, remember these wise words: Your lack of planning does not constitute my emergency.

Even when things are going well, coaches should have a backup plan in place. Keep a pitcher warmed up and ready to go in at a moment’s notice, just in case whoever is in right now needs to come out. Unless there is a huge disparity, a warmed up #3 will probably do better than a cold #2, or even a cold #1.

Also keep in mind the health and safety factor. A pitcher who has not gone through a proper warm-up is at higher risk of injury, especially in and around joins like the shoulders, elbows, knees, and ankles. Giving your pitchers adequate time to warm up before heading into that stressful, high-impact position will make it far more likely she’s ready to go not just this time but the next time you need her too.

Pitching is hard enough on the body, the mind, the emotions, and the spirit. Don’t make it harder by pulling a pitcher in without a warm-up.

With a little planning and forethought you can keep your pitchers healthier and produce better results for the team.

7 Lessons from the 2025 WCWS

Like many coaches I’m sure, over the last couple of weeks I’ve been telling my students that they should watch the Women’s College World Series games. See what they do and how they do it, because in most cases

it’s a master class in how to play the game.

Students aren’t the only ones who can learn from it, however. There were a lot of lessons in there for coaches at all levels as well.

In some cases it was the strategies those coaches followed, whether it was using the element of surprise (such as a flat-out steal of home) or how they used their lineups. In others it was how they dealt with their players through all the ups and downs of a high-stakes series, or even their body language (or practiced lack of it) when things went wrong.

So with the WCWS now concluded and a champion crowned, I thought it would be a good opportunity to recap and share some of those lessons (in no particular order). Feel free to add any you think I may have missed in the comments.

WARNING: There be spoilers here. If you have games stacked up to watch and are trying to avoid learning the outcomes of those games stop reading now, go fire up your DVR, then come back afterwards.

Individual Greatness Doesn’t Guarantee Success

Ok, quick, think about who were the biggest names going into this year’s WCWS. Odds are most of you thought of three pitchers in particular: Jordy Bahl, Karlyn Pickens, and NiJaree Canady.

They have been the big stories all season, and for good reason. All are spectacular players who make a huge difference for their teams.

Yet only one of those names – NiJaree Canady – was in the final series, and her team did not win the big prize. This is not a knock any of these women, because they are all outstanding.

It is merely an observation that for all their greatness, it wasn’t enough in this particular series. To me, the lesson here is not to get intimidated by facing a superstar and fall into the trap of thinking your team simply can’t match up.

Teagan Kavan, the Ace for Texas had almost double the ERA and WHIP versus NiJaree Canady, almost double the ERA of Karlyn Pickens (although their WHIPs were close), and a somewhat higher ERA and WHIP than Jordy Bahl. Yet in the end Kavan was the one holding the champion’s trophy.

Get out there and play your game as a team and you can overcome multiple hurdles as well.

Riding One Pitcher Doesn’t Work As Well As It Used To

Back in the days of Jennie Finch, Cat Osterman, Monica Abbott, Lisa Fernandez, etc., teams used to be able to ride the arm of one pitcher all the way to the championship. That is no longer the case.

One reason for that is the change in format, especially for the championship. It used to be you only had to win one final head-to-head matchup to take home the prize. Now, it’s best two out of three, which extends how much a pitcher in particular has to work, especially if you’re the team coming back through the loser’s bracket.

It’s not that today’s athletes are any less than those of the past either. I’d argue they’re probably better trained and better conditioned that even 10 years ago.

But the caliber of play has continued to increase, and every one of the players is now better trained and better conditioned than they used to be, with science and data leading the way. That elevation in performance makes it that much tougher to play at an athlete’s highest level throughout the long, grueling road to the final matchup.

The stress and fatigue of playing on the edge takes it toll, especially on the pitchers who are throwing 100+ pitches per game. And while the effort of pitching in fastpitch softball may not create the same stresses on the body as overhand pitching, repetitive, violent movements executed over and over in a compressed time period are going to take their toll.

Smart teams will be sure to develop a pitching staff and use that staff strategically to preserve their stars for as long as they can. Yes, when you get to the end you’re going to tend to lean on your Ace more.

But the more you can save her for when you need her at the end, the better off you will be.

(NOTE: This is not a critique of either coach in the championship series. This is more advice for youth and high school coaches who over-use their Aces to build their won-loss record instead of thinking ahead to what they will need for the end of the season.)

In a 3-Game Series, Winning Game 1 Is Critical

Winning that first game gives you some luxuries that can help you take the final game.

When you win game one, you have the ability to start someone other than your Ace because worst-case if you lose you still have one more game to try to win it all. You can bring your Ace back fresher, and you won’t have given opposing hitters as many looks at your Ace as they would have had otherwise.

If you lose game one, it’s do-or-die. You need to do what you need to do to keep the series going so you will pretty much be forced to use your Ace. She gets more tired, and opposing hitters get more looks at her in a short period of timing, helping them time her up or learn to see her pitches better.

That makes it rougher to win game three for sure.

Even the Best Players Make Errors Under Pressure

So there’s Texas, sitting on a 10-run lead in the top of the 5th inning with three outs, then two outs, then one out, then one strike to go. One more out and the run rule takes effect, making them the 2025 WCWS champions. I’m sure their pitcher, Teagan Kavan, was looking forward to it all being done since she’d throw her fair share of pitches in the WCWS too.

But then disaster struck. Texas Tech put the ball in play and a throwing error by Texas put what should have been the third out on base. Another throwing error and a couple of hits later the score is now 10-3 and Texas Tech feels revived.

I’m sure the original error was a play they’ve practiced a million times. But in that situation the throw pulled the first baseman off the bag and kept Texas Tech in the ballgame.

That’s something to remember with your own teams. Even the best players make mistakes and/or succumb to pressure. The key is to not hit the panic button (or the scream at players button) and instead keep your cool so the players calm down and get back to business.

Also notice Texas coach Mike White didn’t pull his shortstop in the middle of the inning because she made an error. Instead, he put his faith in her and she made plays later that preserved the win.

It Ain’t Over ‘Til It’s Over

Same situation but from the Texas Tech side. It would have been easy for them to say 10-0 was an insurmountable lead and begin to let up a little.

Instead, they battled to the final out, and played like they always believed they could still win it. While it would have been tough, if a few more things went their way who knows?

Every player on that side did their jobs to the best of their ability, always believing they could still take the lead. And for a while there it looked like they might.

Now, one thing they had was the luxury of time. With no time limits and no run limits, they had the potential to score enough runs to get back in the game.

It didn’t happen, but it could have. As long as you’re not restricted by time there’s always that chance you can come back. Keep doing your best and you never know what might happen.

Pay Attention to the Little Opportunities

You have to admit the steal of home by Texas Tech was both fun and a gutsy call. I don’t have any inside information on it, but I’m guessing Coach Gerry Glasco knew it was an opportunity long before he called for it. He just had to wait for the right situation.

In watching the replays, it looked to me like the catcher wasn’t paying attention when she threw the ball back, because who would be crazy enough to try to steal home like that? The Texas Tech runner, though, was on a flat-out sprint from the moment the pitch was released and she ended up scoring pretty much unchallenged.

The lesson her isn’t just to keep awareness of what’s happening when you’re on defense, although that’s important. It’s also to think ahead and see what’s happening on the field when you’re up to bat, to see if there are opportunities to advance baserunners or score without putting the ball in play.

It was a gutsy call for sure. But I doubt it was done without a lot of forethought.

Practice the Little Things Too

On the other side of the coin was the hit off the intentional walk in the first game of the championship series. After throwing the first three balls, NiJaree Canady apparently lost a bit of control on the last pitch and Texas took advantage of it, swinging on a pitch that was too close to the plate while the defense was relaxed knowing it was an intentional walk.

Again, I don’t have any inside information but I’ll bet Texas Tech didn’t spend much time practicing intentional walks. Why would they when they had the two-time NFCA Pitcher of the Year throwing for them? Why would she need to walk anyone intentionally?

So when the situation came up, perhaps she wasn’t quite as ready as she should have been. I know you may be thinking “how hard is it to throw a pitch to a spot off the plate for someone who has pinpoint control everywhere else?”

It’s actually harder than you think, and a skill that has to be practiced like any other. Your pitchers are used to throwing strikes. Throwing a ball on purpose may seem as foreign to them as throwing with the opposite hand.

If you think you might throw an intentional walk, or do anything else out of the ordinary for that matter, be sure you practice it first. The less you leave to chance the better chance you have of it working.

Murphy’s Law In Action

Cindy Bristow once told a clinic full of coaches “My girls make the same mistakes your girls do. They just make them faster.” Over the years I have found that to be true.

If things can go wrong they will go wrong. Nothing you can do will change that.

But you can be as prepared as possible, and remember that no one ever sets out to perform poorly. Those things just happen.

Even the best players and coaches make mistakes or have good intentions blow up in their faces. Hopefully we can all learn from them and use that knowledge to help us get better for the next time.

6 Benefits of Playing Under Sandlot Rules

Let me start by acknowledging that today’s ballplayers are far more technically skilled and athletically knowledgeable than they were when I was young lad, and even when I started coaching more than 25 years ago. If you go out to a ballpark this weekend, even to a local B-level or C-level 10U tournament, you’re likely to see a higher level of overall performance than you would have even 10 years ago.

Don’t even get me started on how crazy good high school and college softball players are today.

We can attribute a lot of that growth, in my opinion, to the tremendous amount of information that is available to coaches today as well as the tremendous amount of time teams and individuals invest in structured, organized training sessions and practices. With competition levels already high and improving each year, you’re either getting better or getting left behind.

Yet for all their technical prowess, I think today’s players may be missing out on a few things that are equally important to their level of play – and probably more important to their development as human beings: the benefits of playing under what’s called “sandlot rules,” i.e., unstructured playtime.

Following are some of the benefits that could be gained by downsizing the organized team activities (OTAs) and giving players more time to play under “sandlot rules.” And not just softball but whatever games those players want to play at the time.

1. Acquiring decision-making capabilities

In OTAs, coaches or other adults decide what players are going to do pretty much every minute of every practice or game. They determine who’s going to play where, what order they will bat in, what strategies they’re going to follow, even what uniforms to wear, right down to the color of socks.

Under sandlot rules all of those decisions have to be made by the players themselves. They pick the teams (if teams are needed), agree on the rules, determine what equipment is needed, set the boundaries for play, etc.

Whatever needs to happen to get game or activity going, players get to decide on them. If they can’t decide, that leads to the benefit of…

2. Learning conflict resolution

Let’s say the players want to play a game of softball, but there are no lines on the field. A batter hits a ball down the line and the defense says it’s foul while the offense maintains it was a fair ball.

With no umpire to look to, the players on both sides will have to come to a conclusion. If neither side can convince the other of its position, the likely outcome is the ol’ do-over.

No matter what they determine, however, they will have worked the problem and decided on an outcome. Or they won’t agree on one, in which case the game is probably over and no one gets to play anymore.

Either way, they will have learned a valuable lesson about the value of cooperation and compromise to achieve a higher goal (in this case continuing to play).

3. Developing problem-solving skills

Certainly the situation in point #2 also involves an element of problem-solving too, but I’m thinking of more general problems for this benefit.

For example, let’s say there are enough players to have 7 on each side. But a full team requires 9 on each.

When I was a kid and that was the case, we would close an outfield section (usually right field except for me, who hits left-handed) and have the team on offense supply a catcher. It was understood that the supplied catcher was obligated to perform as if he was a member of the defensive team and do all he could to get the out if there was a play at home, or backup any plays out on the field.

If you only had 4 or 5 kids available to play, you’d switch to a different game such as 500, which incidentally is where most of us learned to fungo, helping build hand/eye coordination and bat control. Whatever the issue is, under sandlot rules there are no adults to solve the problem even make suggestions so it forces the players to work together to overcome any obstacles themselves.

What a concept.

4. Improving athleticism

There is a lot of talk these days about the benefits of playing multiple sports instead of specializing early, especially in terms of cross-training muscle groups. Heck, I’ve written about it myself.

But you don’t need OTAs to get that benefit. It’s all available on the sandlot, or at least your local park.

Want to improve speed, quickness, and agility? Playing tag is a great way to do it, especially if you have two people serving in the “it” role. Nothing brings out competitiveness and causes people of all ages to run fast, cut hard, and move their bodies in impossible ways like trying to avoid being tagged. Remember, though, to let them set the rules.

Want to build some upper body strength? Go find some monkey bars or something else to climb and let them go wild.

They’ll do it with an enthusiasm you don’t usually see during formal pull-up sessions. Add a competitive element of some sort and they’ll drive themselves to exhaustion.

Just be sure to avoid the temptation to tell them what to do. Simply put them in the situation, or better yet encourage them to do it in their free time, and you’ll all reap the rewards on and off the field.

5. Elevating their mental health

Mental health among young people has reached a crisis level, and the decline of independent activity is often cited as one of the leading causes. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 4 in 10 high school students (40%) said they had a persistent feeling of sadness or hopelessness, and 2 in 10 (20%) said they seriously contemplated suicide while 1 in 10 (10%) actually attempted it.

This was a significant increase over the same questions asked just 10-15 years prior. And even more younger students are exhibiting these tendencies at the same time school days and years are getting longer, homework is increasing, and recess time is being cut to just 29.6 minutes a day on average – if they get recess at all.

Giving players of all ages more unstructured free time to “just go and play” may help turn this trend around, resulting in happier, healthier, more well-adjusted, and more productive young people – and adults.

6. Letting them have fun

Always remember that fastpitch softball is a game, and games are meant to be fun. Nobody signs up thinking “boy, I hope we do a lot of work today.”

In pretty much every survey of young athletes you’ll find, the #1 reason they quit sports (often around the age of 13 or 14) is that they’re not fun anymore. Inject more fun in their lives and we can keep more of our players playing longer.

Back to the sandlot

The game of fastpitch softball requires a lot of learning, both on the mental and physical sides, so it’s easy for coaches and parents to not want to “waste time on nonsense.” But that nonsense may be exactly what your players need to perform their best.

Give them the opportunity to get back to the sandlot now and then and you’ll help enhance their overall experience with sports – and help them become the adults they’re meant to be one day.

A Quick Guide to Working With the Littles

Congratulations! You missed your rec league’s organizational meeting and somehow got volunteered to coach an 8-10 year old team.

Or maybe you were once a player and thought it was important to give back to the game you loved so much growing up so you volunteered yourself. Or you’ve started doing private lessons and were looking to fill up your schedule.

Whatever the situation, you’re now faced with the challenge of trying to help one or more kids who just learned how to tie their shoes a couple of years ago now use a windmill motion to throw a ball 35 feet into a strike zone that feels like it’s the size of a baby’s shoe box, hit said pitch with a bat, throw a ball more than 20 feet and get it in the general vicinity of the target (who is hopefully paying attention), catch a ball thrown at them without running away screaming, and learn all the rules, strategies, and general requirements they need to know to play this complex game. Whew!

As someone who has done this for more years than some of the parents of those kids have probably been alive, I can tell you it can be quite challenging. But it can also be quite rewarding, especially when you see those kids’ eyes light up as they do something they’ve never done before, and hear them asking their parents when the next practice is because they can’t wait to come back.

So with that in mind, here are a few suggestions that can make your path to working with the littles a little easier and more comfortable – for you and for them.

Get used to stooping down or kneeling

There is a scene in the movie Hook where Peter Pan first wakes up to the fact that he is Peter Pan. He looks at Captain Hook and says, “I remember you being a lot bigger.”

To which Hook replies, “To a 10 year old I’m enormous.” Or something like that.

That’s how you look to the littles. Even if you’re considered to be short or even very short in the adult world, you’re still likely to loom tall over most of your players, which can make you seem scary. Double that if you’re male.

Squatting, stooping, or kneeling down can put you at their eye level, making you seem less intimidating and more friendly. It can quickly put your players at ease.

On the other hand, when you squat down don’t be surprised if at least some of your players do it too, thus taking away the purpose of squatting down in the first place. Just enjoy the cuteness overload of it and know that if they are reacting that way they’re already starting to see you as one of them.

Try to understand how they see the world

This goes double if you were a college player in my opinion, because like any human being your perspective of something is most likely to be colored by your most recent experience with it.

The most important takeaway you can have here, and probably from this entire blog post, is that kids are not just short adults. That is true of any kids, but especially the littles.

Some probably still believe in Santa or the Tooth Fairy. They’re barely out of their Paw Patrol phase and may still play with dolls or unicorns or trucks or simple video games, or have rich fantasy lives full of imaginary adventures.

In other words their life experiences are very limited, as are the reasoning skills for most of them. You really need to get out of your own head, with all you have learned over a lifetime, and see things from their perspective.

Assume they know nothing about fastpitch softball or its skills and strategies, not to mention life for the most part, and proceed from there.

Speak in words they understand

You may have a great vocabulary and lots of technical knowledge about softball, human anatomy, movement patterns, etc. Good for you, great job on improving your education!

But if you’re going to work with the littles you need to set all of that aside and speak to them in a way they understand. Use small words and keep explanations short and simple.

Instead of saying “Move on the frontal plane” tell them to go sideways. If you’re instructing them on throwing, call the upper arm the upper arm instead of the humerus. Say “see it in your head” instead of “visualize it.”

The more you talk to them with words or concepts they already understand the faster they’ll learn – and the less frustrated you will get.

Fit the drills to their skills – and size

You may be all excited about teaching your players your favorite hitting drill from high school or college, or a new throwing drill you learned from a college coach at a coach’s clinic. But before you trot it out, take a good look at your players and see if it’s a fit, figuratively and literally.

Here’s an example of NOT doing that. At a facility where I give lessons, the last two weeks I’ve watched the cutest little 8U (I presume) team doing hitting drills where they get down on one or both knees and hit off a tee.

Nothing wrong with that in theory. But in practice the problem is when they are on one or both knees the ball is about nose-high even with the tee all the way down. So all they’re really being taught is to swing at pitches out of the zone.

Making things worse, at times they are doing one-handed drills. Most of those girls can barely hold their bats up with two hands, much less one. And yes, they are choking up on the bat when they’re doing it.

They’d be much better off standing up and learning the basic sequence of how to move first. Then, when they get a little bigger, stronger, and more accomplished, they can work on isolating different parts of the swing.

The same goes for many other parts of the game. Think of it as a pyramid.

Start with the very general as the foundation, then work your way up to more narrow and advanced components as they master the basics. They’ll learn better, and your team will perform better while having more fun.

Exercise – or learn – patience

This is probably the most important skill you can develop as a coach. Not just for the littles; for everyone, but especially for the littles.

Remember their brains are still in the process of forming, and it will be a long time before they’re fully formed. Like their mid-20s.

Also remember that everyone is an individual, so the pace of their development in various areas will be different. Some will be able to do things right away, others will struggle, no matter how hard they try.

Be patient with all of them and meet them where they are. Praise progress, not just success.

When you get frustrated, take a deep breath and maybe try to explain things in a different way. Find something they can relate to and use that to help explain what you want to them. A great coach will have 100 different ways to say the same thing.

You’ll also need patience when it comes to their attention spans. Some littles are really good at paying attention. Others have a circus going on in their heads at all times so it can be a little tougher to keep them on-task.

I’ve had some of those. One in particular I can think of is a girl named Katie, who was a pitching and hitting student.

She was a good athlete, even at that age, but at any given time her brain could turn on a dime and she’d be far away from what we were trying to do, and I’d have to try to corral her back again. Her mom was a teacher, too, so she’d get aggravated when Katie wouldn’t pay attention.

I, on the other hand, chose to find it amusing and would laugh at her flights of fancy, which I think helped build the relationship.

As she got older, her focus got better and she turned out to be a terrific pitcher, the kind that typically didn’t need to throw more than 10-12 pitches to get through an inning. Although she eventually gave up pitching she went on to play high-level travel ball and become a high school varsity starter as a freshman in both softball and basketball. (I had nothing to do with basketball, just pointing it out for accuracy’s sake.)

Again, everyone develops at their own pace, and the weakest or least attentive player today may go on to become the best player on her team down the road. With a little patience you can help get her there.

CAVEAT: The one area where that doesn’t work is the kid who is purposely being disrespectful or disruptive or uncooperative. I have no patience for that. If they clearly don’t want to be there nothing wrong in my opinion with telling them to get on board or get out. It’ll save everyone a lot of heartache.

Be kind

I shouldn’t have to say this but again, based on my extensive experience watching how the littles are treated in games and practices, it needs to be said anyway.

None of your players are purposely trying to walk every hitter, strike out, drop easy pop-ups, boot grounders, forget to tag up, throw the ball into the parking lot, or commit any of the other basic softball sins. That stuff just happens.

When it does, you don’t have to scream at them or berate them or call them names. Instead, help them learn from their mistakes in a kind and respectful way.

Be encouraging. Tell them you believe in them, and that they should believe in themselves.

Give them corrections when and where needed without belittling them (no pun intended). You may have to do that a few times before it really sinks in, but keep doing it.

Years down the road they will remember you fondly, and may even invite you to their wedding! Help them feel good about themselves, even when you’re secretly mad as heck at them, and you’ll not only help them become winners as ballplayers; they’ll become winners as human beings.

Have realistic, age-appropriate expectations

Even though I’ve been doing this a long time I’m still shocked at some of the stories I hear about the expectations coaches can have of their littles.

Pitching is a good example. There are coaches of 8U and 10U teams that insist their pitchers have to “hit their spots” or throw a certain velocity if they want to pitch for the team.

First of all, at those ages “hit your spots” should mean throwing strikes enough of the time to keep the game moving. To expect kids who are just learning how to pitch to throw to an exact spot with precision is simply ludicrous.

Expecting certain velocities is silly too given how much of a size difference there can be as kids develop. To think a pitcher who stands less than 5 feet tall and weighs 70 lbs. will throw as hard as a pitcher who is 5’4″ and weighs 120 lbs. is unrealistic, to say it kindly.

These ages (and I will include 12U in this one as well) are about development and gaining experience, not meeting certain “minimum standards.” That extra small little will grow someday, in her own time, and my actually pass by all the girls who started with greater physical advantages because she wanted it more.

You just never know. Your job as the coach is to encourage and create opportunities for every kid on the team so they develop a love for the sport and go on to become the best they can be. The rest will sort itself out down the road.

The rewards are there

I won’t kid you. Working with the littles isn’t easy; it definitely has its challenges with coordination and attention spans being at the top of the list.

(On the other hand, when they get to be teens with attitudes and petty squabbles you may long for the days when your biggest coaching challenge was getting them to keep their elbows up when they throw.)

Just keep in mind you have the unique opportunity to shape the next generation of fastpitch softball players, and perhaps coaches after that. What you do matters than you may realize.

Thank you for taking on this important challenge. Now go get ’em, coach!

Energy Creation: The Rolling Snowballs Corollary

This seems like an apt analogy since as I write this much of the USA is still dealing with a fair amount of snow, including many places that rarely get any. Welcome to my world, although we actually haven’t gotten much all winter.

Anyway, the other day I was trying to explain the concept of acceleration to a young pitcher. We were talking about the need for her arm to pick up speed down the back side of the circle instead of staying at one speed if she wants to throw harder.

Then an idea hit me, thanks to a childhood misspent watching Saturday morning cartoons.

“Think about a snowball rolling down a hill,” I said. “At first, the snowball is small. But as it rolls down the hill, the snowball starts picking up more snow, getting bigger and bigger. Then, when the snowball reaches the bottom and stops, the snow explodes all over the place!

“That’s what needs to happen with your pitching arm,” I continued. “As you come down the back side you start moving your arm faster, which gathers more energy like the snowball gathers snow, until the ball explodes out of your hand at the end.”

That made perfect sense to her. The more the snowball moves downhill the faster it goes and the more snow (energy) it picks up.

Ergo (love that word, rarely get to use it in a sentence), getting that arm to move faster down the back side of the circle is critical to maximizing speed. Logical, right?

But that doesn’t mean pitchers can always do it. Some will do it naturally. Others will do it once your bring it up. But some have to unlearn old movement patterns and replace them with new ones before they can execute it.

One of the best ways to help them learn that acceleration is by moving the pitcher in close to a net or tarp, having her stand with her feet and body at 45 degrees to the target, and then throwing with a full circle, emphasizing the speed on the back side of the circle. You can also do that with six or eight ounce plyo balls into a wall.

I also prefer they move their feet as they do it since body timing is also crucial to great execution.

The key here is feeling the arm moving as quickly as it can. But there’s another caveat.

To really make this work and get the acceleration, the arm has to be loose and the humerus (upper arm) has to be leading with the forearm trailing behind, i.e., throwing with whip. Moving the whole arm in one piece, as you do when you point the ball toward second base and push it down the circle, will not yield the same level of results. In fact, it could cause injuries.

Once the pitcher can execute this movement from in-close, start moving her further away and trying it again. Take your time with this process, because if you move her back too fast and she perceives the target is too far away she will start muscling it to make sure it gets there rather than letting it move naturally.

At each step, take a video and look to make sure there is at least somewhat of a bend or hook at the elbow instead of a straight arm. If not, move her back up or slow her down temporarily so she can get the proper mechanics.

Then speed it up and try again.

By the way, the energy snowball concept is not just for pitchers. This type of acceleration into release or contact is also critical for overhand throwing and hitting.

Or pretty much any other athletic skill requiring power.

Now, if you’re an adult with lots of real-world experience, all of this may seem obvious to you. You may even be wondering why I’m spending so much time on it.

But a young player, or even a young adult player, may not have the real-world understanding of basic physics or biomechanics to tie acceleration into energy production. For them, it’s helpful to put it in a context that they can easily comprehend based on what they have already seen.

Even if it comes from a Saturday morning cartoon.

If you have a player who’s struggling to understand the concept of acceleration into action, try talking about the rolling snowball. It just might break the ice with them.

My good friend Jay Bolden and I have started a new podcast called “From the Coach’s Mouth” where we interview coaches from all areas and levels of fastpitch softball as well as others who may not be fastpitch people but have lots of interesting ideas to contribute.

You can find it here on Spotify, as well as on Apple Podcasts, Pandora, Stitcher, iHeart Radio, or wherever you get your podcasts. If you’re searching, be sure to put the name in quotes, i.e., “From the Coach’s Mouth” so it goes directly to it.

Give it a listen and let us know what you think. And be sure to hit the Like button and subscribe to Life in the Fastpitch Lane for more content like this. Commercial over.

Snow roller photo by Perduejn, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Be the River, Not the Rock

Here’s a simple question for you today: which is strong, the river or the rock that sits in the middle of it? The answer is it depends on your point of view.

Taken at a glance, a snapshot in time if you will, it appears the rock is stronger. After all, the rock stands steadfast, unmovable, while the river must divert around it.

But if you take a longer-term view, the answer is the river, because over time it will erode the rock until the rock is no longer an obstacle to its path.

I know, very Kung Fu of me (which is probably where I got the idea). You can hear the pan flutes even as you read this.

That doesn’t make it any less true, however. Which is a good lesson for playerstrying to learn or improve a challenging skill such as pitching or hitting, as well as for coaches trying to get the best out of their teams.

Players

Let’s start with players. They can take the rock approach to learning new skills or improving/revamping current ones for a variety of reasons, including:

- What they’re currently doing has worked for them before. For example, a 12 year old pitcher who is used to pushing or lobbing the ball toward the plate instead of using her whole body to throw. She threw more strikes than the other pitchers she knows and if that’s her only measurement of success why change? .

- They’re not comfortable doing something new. With minor exceptions, who is? It’s a lot easier to do what you’ve always done than to change it.

- When they try something new their performance goes down (in their mind). Such as a hitter who used to make weak contact but is now swinging and missing while trying to learn a new way to swing the bat.

- They just don’t want to change. Typically seen with players who are forced to take lessons by their parents or players who believe they are better than they actually are (big fish in a small pond).

The problem here, as they say, is if you do what you always did, you’ll get what you always got. But if others around you are improving their games, what you always got may not be good enough anymore and you’ll find yourself sinking down the batting order or the pitching rotation – or maybe even out of the starting lineup.

The important thing to remember when players make a change is that it doesn’t have to be permanent. Try something for a little while and see if it works. If it doesn’t, you can always try something else.

I do that a lot with my students. I have an idea, based on science and experience, of what will work, but I’m not omniscient. (That means all-knowing for those who don’t feel like looking it up.)

Try it and see how it feels. Sometimes you’ll hit farther or throw faster.

Sometimes it will throw you off your game completely. But you don’t know until you try it.

Remember, as the rock wears down the river changes its course. Be the river.

Coaches

Coaches, too, can benefit by taking the river approach instead of being the rock.

We see the rock approach a lot. Something new will come along and you’ll have a percentage of the coaching popular who will say “I’ve been doing it my way for 10/20/30 years and have had success. Why should I change?”

The answer, of course, is because new discoveries are being made all the time – data-based discoveries that can help players get better, shortcut the learning process, overcome deep-seated challenges that are built into the DNA, or otherwise improve.

It’s the same with game strategies. You may have followed the same playbook for X number of years, but what if there is information out there that could turn a few more of those losses into wins because you knew how to use it?

The best coaches I know are constantly scouring every source they can find to obtain new information in the hopes that it might help them. They are moving their knowledge forward like the river instead of standing in one place like the rock.

Imagine if you could discover just one little tip or trick or way of looking at things that would give you a significant advantage over your rivals. That’s the premise of the book and the movie Moneyball.

The Oakland Athletics used data to find players others didn’t value very highly to help them field a team that could win 100 games while fitting their very limited budget. It was a game-changer for them, and for the rest of Major League Baseball who followed that example.

Besides, learning new things is fun. Again, you may try something only to find it doesn’t work for you.

That’s ok. Now you know more than you did before.

But if you do discover some new strategy or approach that pays dividends you’ll be glad you gave it a try. Even if you had to change your world view a little.

It’s easy to be the rock, staying in one place while the world rushes past you. But eventually it will wear you down too. Be the river.

Check Out Our New Podcast

Speaking of learning new things, my good friend Jay Bolden and I have started a new podcast called “From the Coach’s Mouth” where we interview coaches from all areas and levels of fastpitch softball as well as others who may not be fastpitch people but have lots of interesting ideas to contribute.

Our first two episodes are in the books. In the first we spoke with pitching guru Rick Pauly of PaulyGirl Fastpitch, and in the second we heard from Coach Sheets (Jeremy Sheetinger), head coach of the Georgia Gwinnett College baseball program.

You can find it here on Spotify, as well as on Apple Podcasts, Pandora, Stitcher, iHeart Radio, or wherever you get your podcasts. If you’re searching, be sure to put the name in quotes, i.e., “From the Coach’s Mouth” so it goes directly to it.

Give it a listen and let us know what you think. And be sure to hit the Like button and subscribe to Life in the Fastpitch Lane for more content like this. Commercial over.

River photo by Matthew Montrone on Pexels.com

Book Recommendation: “Crunch Time”

We’ve all seen it or experienced it: the player or coach who is great in practice (aka a cage warrior) and seems like he/she should be a star, only to struggle when they get into a game. It’s frustrating to watch, especially because the breakdowns often seem to happen at the worst possible time, yet helping them break free of that mindset can be extremely challenging.

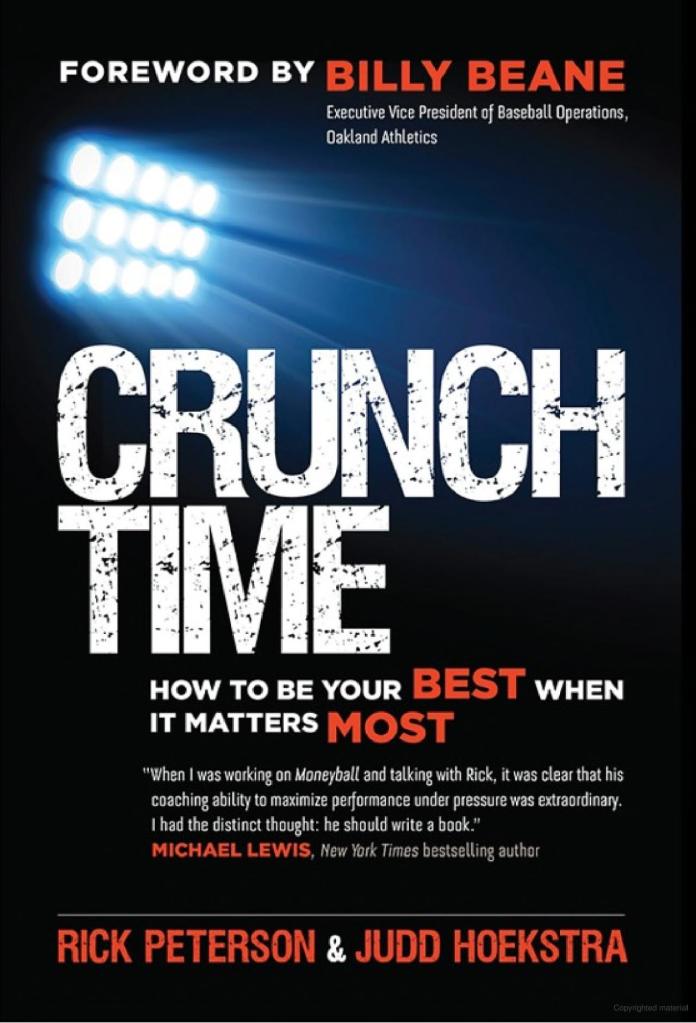

Fortunately I recently read a book that addresses this very issue. It’s called, “Crunch Time – How to Be Your Best When It Matters Most” by Rick Peterson and Judd Hoekstra.

If you’re not familiar with them, Rick Peterson is currently Developer of Pitching Development for the Baltimore Orioles, was the pitching coach for the Oakland A’s during the “Moneyball” era, and is considered one of the top pitching coaches in all of Major League Baseball.

Hoekstra is a bestselling author of books on leadership as well as a vice president at The Ken Blanchard Companies, a consulting firm that specializes in training business leaders at organizations of all sizes. Pretty good pedigrees for both authors.

While the book’s lessons apply to a general audience rather than specifically to baseball or softball, it definitely speaks to the challenges players and coaches face when challenged to perform under extreme pressure. The nice thing is it’s a pretty quick read too; I finished it cover-to-cover while on a 4.5 hour flight coming home from vacation.

The central theme of the book is that when you are facing a difficult situation you need to reframe it in order to manage the stress and allow yourself to perform the way you know you can. In other words, instead of seeing that difficult situation (such as an at bat where the game is on the line) as a threat, view it as an opportunity.

So in that example, the immediate threat is losing the game if the player doesn’t perform well, i.e., get a hit. But the underlying threats are that coaches and teammates will be mad at the player, the player might get benched, teammates won’t want to associate with the player, one or more parents might be angry with the player, the player will be embarrassed, etc.

The result is the player gets so caught up in potential consequences (especially if he/she has faced this situation before and failed) that he/she freezes up and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s difficult to perform at a high level when you’re paralyzed with fear.

After explaining the need for reframing the authors then get into several techniques to accomplish this task in subsequent chapters, including:

- Reframing from trying harder to trying easier

- Reframing from tension to laughter

- Reframing from anxiety to taking control

- Reframing from doubt to confidence

- Reframing from failure to learning moment

- Reframing from prepared to overprepared

Each chapter not only talks about the techniques but offers anecdotes from the authors’ experience of how they were applied. For example, Peterson talks about making mound visits during MLB games where he used humor to help a pitcher put what was happening into perspective, allowing him to get past an initial walk and single in order to strike out the heart of the opposing lineup and get out of the inning.

One of the nice things is that unlike many “mental game” books, applying the lessons in “Crunch Time” doesn’t require going through a plethora of exercises in order to master the techniques. It’s more of a philosophical approach presented in a simple form that makes it easy to grasp the lessons so you can begin applying them right away.

While I’ve been talking about how coaches can use the lessons in “Crunch Time” to help players, they can also use it to help themselves become better coaches at critical points of the game.

In that way it reminds me of a story legendary football coach Bill Walsh told in his book “The Score Takes Care of Itself.” Walsh was one of the first if not the first to develop the laminated play calling sheets all football coaches now have with them throughout the game, and was lauded as an innovator for doing it.

Yet in his telling, the reason he did it wasn’t because of some stroke of genius. It was the result of him having trouble making quick decisions under pressure. By creating the play calling sheets when he was calm and reasoned, i.e., before the game, he could just look at what he figured out already and just follow it, relieving the pressure of those in-game, critical decisions.

The lessons of “Crunch Time” can help in the same way. Take the international tie breaker, probably one of the most high-pressure situations in softball coaching because often any minor miscue or poor decision can lead to the loss of the game and possible elimination from a tournament or conference championship.

Rather than viewing a loss as a threat, by reframing it as an opportunity (we’ve prepared well for this situation so we have an advantage over our opponents who are clearly nervous about it) coaches can make strategic decisions with confidence, knowing their teams will execute, and can convey that sense of confidence to the team to keep them from being rattled and making those types of mistakes.

As I said earlier it’s a pretty quick read but there’s a lot of great thinking contained within the content. If you’re looking for techniques to help your players perform better, and/or ways to help grow your own coaching abilities, I recommend you pick up or download “Crunch Time.”

Captain Picard’s Lesson on Winning, Losing, and Errors

Sorry to nerd out on this one, but there is a great Star Trek: The Next Generation episode called Peak Performance that puts some perspective into the challenges of competing in fastpitch softball. Even if you’re not a fan you might one to check this one out.

The part that’s interesting here is a side story involving Commander Data, the highly advanced android crew member. An outsider named Kolrami who is a grandmaster at a game called Strategema (sort of a holographic version of Space Invaders) comes on board and quickly irritates the crew with his arrogance.

A couple of crew members encourage Data to use his computer brain to take Kolrami down a peg by challenging him to a game of Strategema. At first reluctant, Data finally does it to defend the crew’s honor – and promptly gets his butt kicked by his flesh-and-blood opponent in about a minute.

Shocked, Data immediately surmises there must be something wrong with his programming and tries to take himself off duty until he figures out where the “problem” is. Captain Picard, who is captain of the ship, rather harshly tells him no he can’t do that, he needs Data, and that Data should quit sulking even though Data has no emotions and so presumably no capacity to sulk.

Then Picard tells Data something that every fastpitch softball coach, players, and parent needs to hear: It is possible to make no errors and still lose.

In our case I’m not talking only about the physical errors that get recorded in the scorebook. Playing error-free ball and losing happens all the time.

I’m talking more about the strategic decisions and approaches to the game that seem like they’re sound but still don’t produce the desired results (a win). Here’s an example.

There are runners and second and third with one out in the last inning of a one-run game. The defensive team opts to intentionally walk the next hitter to load the bases in order to create a force at home and potentially a game-ending double play at first if there’s time. They also pull their infield in to give them a better shot at that lead runner.

The next batter after that hits a duck snort single behind first base that takes a tough hop and rolls to the fence after landing fair and two runs end up scoring.

No errors were made, and the strategy was sound. But the result is still a loss.

Here’s another one from my own experience. Down one run with no outs in a game where they have been unable to hit the opponent’s pitcher, the offensive team finally gets a runner on first.

She’s a fast, smart, and aggressive baserunner, so putting the ball in play somehow could go a long way toward tying the game. The obvious solution would be a bunt to advance the runner to second, giving the offense two shots to bring her home from scoring position.

But the defense knows that and is playing for the bunt. So the offense opts for a slug bunt (show bunt, pull back, and hit the ball hard on the ground) combined with a steal of second. If the hitter can punch it through the infield the runner on first, who already has a head start, will likely end up on third and might even score, depending on how quickly the defense gets to the ball. Best case the batter will end up on second, as the potential winning run, worse case with good execution she’s on first.

Unfortunately, the batter does the one thing she can’t do in that situation – hit a weak popup to the second baseman. The batter is out and the runner who was on first gets doubled off.

Now, you can argue that the failed slug bunt was an error, but was it really? It was a failure of execution but not necessarily a mistake in the classic sense. It was just one of those cases where the hitter lost the battle to the pitcher.

The point is that sometimes, despite our best efforts and doing all we can to play the game correctly, things don’t work out the way we’d like. There are things that happen beyond our control that can influence the outcome of a play, an inning, or a game.

We can’t beat ourselves up over it or spend endless time second-guessing ourselves. We learn what we can from the experience and move on.

Sometimes we make different decisions the next time – and sometimes we don’t – and hope for a different outcome.

In case you’re wondering about Data, at the end of the episode he requests a rematch. This time he keeps the game going until Kolrami finally gives up in frustration.

When asked about it, Data explains that Kolrami entered the second game assuming both he and Data were trying to win and played accordingly. But Data’s strategy was to play not to lose, basically playing defense the whole time, until his opponent essentially forfeited the game, giving Data the victory.

Anyone who has played an international tie breaker can relate.

Not every decision you make on the field is going to work out the way you hoped, even if you’re making it for the right reasons. All you can do is learn from the experience and hope it works out better the next time.

Captain Picard photo by Stefan Kühn, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

There’s More to Calling Pitches than Calling Pitches

One of my favorite jokes is about a guy who goes to prison for the first time. As he’s being walked to his cell by a guard he hears a prisoner yell “43!”, which is followed by howls of laughter from the rest of the population.

About 20 seconds later someone else yells out “17!” and again there is laughter. After a couple more numbers are called out the new guy asks his escort what that’s all about.

“A lot of our population has been here a long time and has heard the same jokes over and over,” the guard explains. “To save time, each joke has now been assigned a number. Someone yells the number and the rest react to the joke.”

“Hmmm,” the new guy says to himself, “seems like a good way to try to fit it on day one.” So he takes a deep breath and calls out “26!”, which is followed by silence.

“What happened?” he asks the guard. “Why didn’t anyone laugh?”

To which the guard replies sadly, “I guess some people just don’t know how to tell a joke.”

The same can be said for pitch calling in fastpitch softball. While it might seem straightforward, especially with all the data and charts and documentation available (including this one from me), it’s actually not quite that simple.

The fact is pitch calling is as much art and feel as it is science and data, and like the newbie prisoner trying to fit in, some people have a natural knack for it and some don’t.

That can be a problem because nothing can take down a good or even great pitcher faster than a poor pitch caller.

Here’s an example. There are coaches all over the fastpitch world who apparently believe that pitch speed is everything. As a result, they don’t like to (and in some cases refuse to) call changeups because they believe the only way to get hitters out is to blow the ball by them.

But the reality is even a changeup that’s only fair, or doesn’t get thrown reliably enough for a strike, can still be effective – as long as it’s setting up the next pitch. And if that changeup is a strong one, it can do more to get hitters out than a steady diet of speed. Just ask NiJaree Canady, who can throw 73 mph+ through an entire game but instead leaned heavily on her changeup during the 2024 Women’s College World Series.

The reality is the ability to change speeds, even if it’s going from slow to slower, will be a lot more effective in most cases than having the pitcher throw every pitch at the same speed no matter how fast she is. Sooner or later good hitters will latch onto that speed and the hits will start coming.

There’s also the problem of coaches falling into pitch calling patterns. Remember that great change we were just talking about?

If you’re calling that pitch on every hitter and hitters are having trouble hitting your pitcher’s speed, the hitters can just sit on the changeup and not worry about the rest. It gets even worse if you’re calling a particular pitch on the same count all the time.

A truly great pitch caller is one who can look at a hitter and just feel her weaknesses. That great pitch caller can also see what the last pitch did to the hitter and call the next pitch to throw that hitter off even more.

I’ve watched it happen. When my younger daughter Kim was playing high school ball she had an assistant coach who was a great pitch caller.

She was never overpowering, but she could spot and spin the ball. The coach calling pitches knew her capabilities, and when they went up against a local powerhouse team that had been killing her high school the last few years he used those capabilities to best advantage.

The team lost 2-1, due to errors I might add, but that was a lot better than the 12-1 drubbings they were used to. The coach called pitches to keep the opposing hitters guessing and off-balance all game, Kim executed them beautifully, and they almost pulled off the upset.

The coach didn’t have a big book of tendencies, by the way. He just knew how to take whatever his pitchers had and use it most effectively.

And I guess that’s the last point I want to make. All too often pitch callers think pitchers need to have all these different pitches to be effective.

While that can help, a great pitch caller works with whatever he/she has. If the pitcher only has a fastball and a change, the pitch caller will move the ball around the zone and change speeds seemingly at random.

The hitter can never get comfortable because it’s difficult to cover the entire strike zone effectively.

Add in a drop ball that looks like a fastball coming in and you have a lot to work with. In fact, for some pitch callers that’s about all they can really handle; throw in more pitches and they’re likely not going to understand how to combine them effectively to get hitters out.

Some people have the ability to call pitches natively. They just understand it at the molecular level.

For the rest, it’s a skill that can be learned but you have to put in the time and effort to get good at it, just like the pitchers do to learn the pitches.

Watch games and see how top teams are calling pitches. Track what they’re throwing when – and why.

Look at the hitters, they way they swing the bat, the way they warm up in the on-deck circle, the way they walk, the way they stand, the way they more. All of those parameters will give you clues as to which pitches will work on them.

Then, make sure you understand how they work together for each pitcher. For example, maybe pitcher A doesn’t have a great changeup she can throw for a low strike, but the change of speed or elevation may be just enough to make a high fastball harder to hit on the next pitch.

Your pitchers aren’t robots, they are flesh and blood people. So are the hitters. If you understand what you want to throw and why in each situation you’ll be on your way to becoming a legend as a pitch caller – and a coach your pitchers trust to help them through good times and bad.