Monthly Archives: February 2026

Some Players Make You Look Like a Better Coach; Others Make You Become One

Anyone who has coached for any period of time knows there are basically two types of players.

The first type makes you look like a better coach. You know the type.

You can pretty much tell them anything – even if it’s the stupidest possible thing you could say – and they will be successful. They have the raw athleticism to find the right way to do things because their bodies just intrinsically understand how to move.

You can put them into a position they’ve never played before and they will look like they’ve been doing it all their lives. In fact, people on the sidelines will probably wonder why you HAVEN’T had her there the whole time.

Then there are those who make you become a good coach.

They have not been blessed with tremendous natural athleticism. While some are reasonably competent on their own, many have no real idea how to move their bodies in anything even resembling an athletic way.

You how them how to swing a bat and then they stand flat-footed and pull the bat around as if it’s a sledgehammer. You try to show them how to catch a ball and it looks like they’re afraid it’s going to bite them.

You try to show them how to throw the ball back and it looks like someone trying to unfold a one-person tent (or put away one of the old Jugs pop-up nets).

And pitching? Fuhgeddaboudit. If there’s a way to do it right, she will immediately find its polar opposite.

The ones who make you look like a good coach are really fun to work with, no doubt about it. And they’re good for the ego too.

A lot of coaches love to point to their very best players and show them off as though it was their great teaching that made them the way they are. Surely the coach helped them with that process.

But as I always say, if it was the coach who made them so good then all of that coach’s players would be equally as good. They’re not.

Often, though, it’s the ones who make you a good coach who have the most impact on your life. First of all, you can’t just tell them any old thing and have it work.

You have to figure out how to explain things to them, or demonstrate things to them, in a way they can understand and then execute. Often that means being creative in your approach and coming up with ways of teaching you would have never done otherwise.

The good news is each of those is unique, which allows you to build your coaching toolbox and expand your coaching reference library tremendously. All of which helps you build your own confidence as well.

There is also a lot of satisfaction in teaching a player to do something she just wasn’t capable of doing before. Seeing her get her first hit in a game, or pitch her first strikeout, or make a great catch, or make a perfect throw across the infield to get the out for the first time, gives you a feeling of pride that simply can’t be matched.

There’s no doubt that the players who make you look good will help you win a lot of games. Appreciate them when they come along, but be sure to keep your contributions to their success in perspective.

While they can be more challenging, especially in the beginning, the players who make you a good coach will likely hold a special place in your heart because you’ll know you gave them an opportunity they would not have had otherwise. It’s still up to them to put in the work, but when they do it’s magic.

Why Coaching Different Levels Is Like Teaching in School

The other week I was waiting for my first lesson to come in when my friend and fellow coach Dave Doerhoffer sat down next to me sighing and shaking his head. Dave is an assistant coach at Vernon Hills High School (as well as a private hitting instructor).

As part of that role Dave, along with head coach Jan Pauly, helps oversee instruction for the Stingers travel teams that feed VHHS. On that day his head shaking had to do with the complicated instruction one of the coaches for a 10U team was giving to his players.

I won’t go into details to spare anyone embarrassment, but the gist of it was that while what was being instructed was technically correct for an older player, it was too much for a younger player who just needs the basics to absorb.

This is something that’s probably more common than most coaches and parents realize. Coaches go to a coaching clinic featuring D1 college coaches explaining how they teach this technical aspect (such as footwork at first base) or handle that situation (such as runners on first and third).

Then the travel coaches, all fired up as they ought to be, come back and try to apply those principles to their younglings. Usually with disastrous results. Players get confused, or don’t yet have the skills or experience to apply what’s being taught, and what should be good outcomes become bad ones instead.

Here’s where coaches can learn something from the way school subjects are taught. In language arts, math, science, etc., the early grades start with the very basics, allow their students to learn those, then build on that knowledge when they are ready and able to take the next step.

Take math, for example, Teaches don’t try to teach differential calculus or advanced algebra in first grade. (Thank goodness because I would have never made it out of first grade.)

They start with simple addition and subtraction, then move to multiplication and division. They continue to build on those skills little by little through multiple grades until they can handle more complex and more abstract mathematical principles.

It’s a slow build over time, not just jumping right to the difficult stuff because it’s cool or will make the teacher look good.

The same goes for vocabulary. Young students start with simple words they use and hear every day (except for those words), then learn more complex ones as their basic understanding grows.

Otherwise all that will happen is the teachers will obfuscate the intention in a torrent of enigmatic gibberish until any learning is diffused and the results are ineffectual. So there.

Coaches first need to put themselves into the shoes of their players, evaluate what those players know (if anything) about fastpitch softball, and work from there. Teaching them how to execute a trick play for first and third when those players can barely throw and catch just doesn’t seem like a good use of time or resources.

By the way, this doesn’t just apply to the very young, i.e., 8U, 10U, or 12U players. Ask some college coaches and they will probably tell you stories about good players who lacked basic knowledge on some aspects of the game, such as how to tag up on a fly ball and when you can run. (It’s when the ball is first touched, not when it’s caught.)

When I was coaching teams I learned the hard way not to assume your players know ANYTHING you THINK they ought to know. If you take the stance that if you didn’t teach it directly to them they don’t know it, no matter what they age, you will avoid some ugly surprises just when you need those least.

The bottom line is as a coach you need to look at what your players know and can do, then introduce new concepts that fit within those capabilities. Your players will learn the game better, in a more logical fashion, and you’ll avoid the preventable mistakes that keep us all up at night.

School photo by Ksenia Chernaya on Pexels.com

What It Takes to Really Learn Something (or Unlearn Something)

When I was but a lad heading into high school, my heart’s greatest desire was to learn how to play the guitar. Partially because I loved music, but also because I thought doing so would help me meet girls.

(Don’t judge, Eddie van Halen started on guitar for the same reason, although he did a little better than me on learning it.)

Anyway, for my 14th birthday (just as the summer started) my parents bought me the cheapest piece of junk available that will still work, a $20 Decca guitar from Kmart. But I didn’t care – I had a guitar, along with a little songbook with songs like Born Free and Red River Valley that had the little finger placement charts above every chord.

I pretty much spent the entire summer locked in my room for 4-6 hours a day every day, playing the same old songs over and over until they began to sound like actual songs. In a month I felt comfortable enough to play that guitar in front of my parents and a couple of their friends.

Within a couple of months of starting I bought my first “real” guitar for $100 out of my 8th grade graduation money – a Suzuki 12 string that I still own to this day. It’s not very playable anymore but I still keep it around for sentimental reasons.

I tell you this story to point out a valuable lesson: if you really want to get good at something, you can’t just dabble at it or put in time against a clock. You have to work at it deliberately, with a goal and a sense of purpose.

In other words, you have to know your “why” or you’re just going to spin your wheels.

So if you’re a pitcher who is trying to increase her speed or learn a new pitch, you can’t just go through the motions doing what you always did. You can’t just set a timer and stop when the timer goes off.

You have to dig in there and keep working at it until you make the changes you need to make to reach your goal.

If you’re trying to convert from hello elbow to internal rotation, you can’t just throw pitches from full distance and hope it’s going to happen. You have to get in close, maybe slow yourself down for a bit, and work on things like upper arm compression and especially forearm pronation until you can do them without being aware of them.

It might take a few hours or it might take a month of focused, deliberate practice. But you have to be willing to do whatever it takes to get there.

The same goes for hitters. If you’re dropping your hands as you swing or using your arms instead of your body to initiate the swing you’re not going to change that overnight by wishing for it.

You have to get in there and work at it, and keep working at it until you can execute that part of hitting correctly. No excuses, no compromises; if you want to hit like a champion you have to work like a champion.

There will sometimes be barriers that seem insurmountable, and no doubt you’ll get frustrated. But there is some little thing holding you back and you attack it with ferocity, with a mindset you won’t let it defeat you, sooner or later you will get it and be able to move on to the next piece.

When I first learned how to play an “F” chord it was really difficult. It requires you to use your fingers in ways other chords don’t, especially when you’re a beginner.

But I needed to master that “F” chord cleanly so I could play certain songs, so as physically painful as it was (especially on that cheap little Decca guitar) I kept at it for hours on end until it was just another chord among many in the song.

The same will happen for you if you work at it. The thing you can’t do today will become easy and natural, and that will put you in a better position to achieve your larger goals.

Yes, it takes a lot to make a change, especially if it’s from something you’ve been doing for a long time. Old habits die hard as they say.

But if you approach it with passion and purpose you’ll get there – and you’ll be better-positioned for your next challenge. .

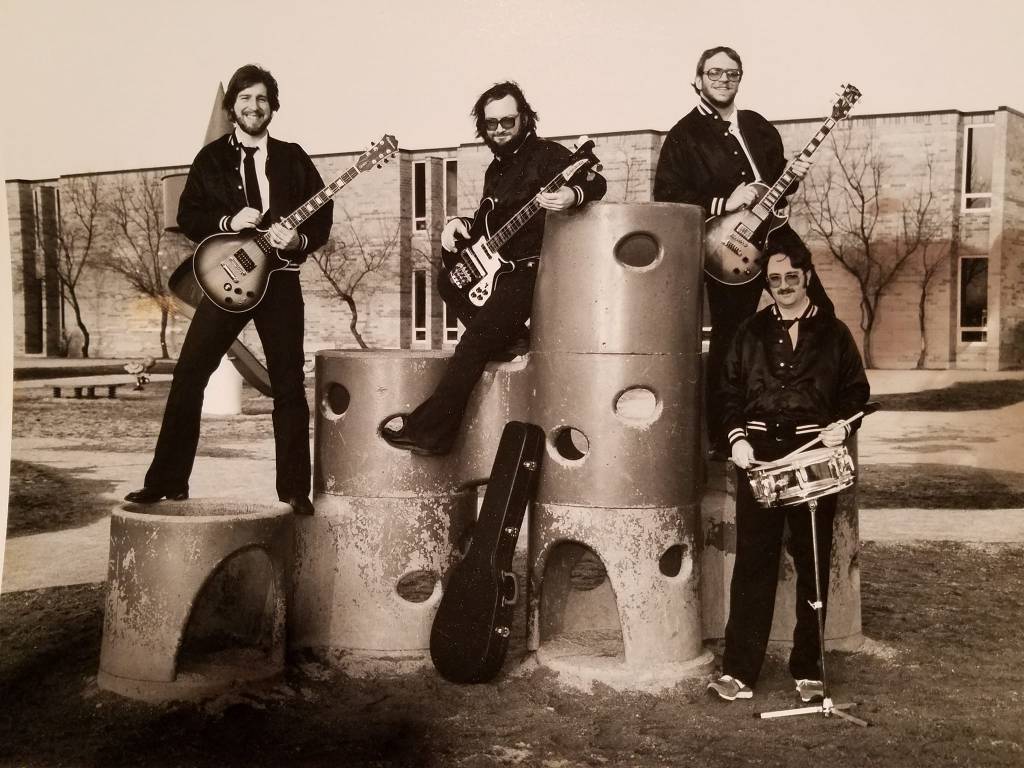

BONUS CHALLENGE: Yes, one of those young fellows up there in the top photo is me. See if you can guess which one and put your choice in the comments below. (HINT: It may not be the one you think.)

The Odds Are Stacked Against You in Fastpitch Hitting

A few days ago I was doing a hitting lesson with one of my students, a young lady named Avery. We got to talking about why the success rate for hitting in fastpitch softball is generally so low.

That’s when she said something profound that her mom Abbey had told her that I hadn’t really thought about in that way: Hitting is 9 on 1.

I think most of us tend to think about the battle between the pitcher and the hitter, i.e., how the pitcher is trying to get the hitter to miss the ball or at least mis-hit if she does make contact so doesn’t go too far. But while the hitter is up at the plate standing alone, the pitcher has one other person in front of her and seven others behind her to help her get the out on that weak hit.

That’s a pretty unfair advantage, don’t you think? Picture a basketball game, or a soccer match, or hockey game, or pretty much any sport where scoring means getting the object at the center of the game into the other team’s goal.

You don’t have to be Mr. Vegas to figure out who is going to win that contest, no matter how skilled the player on the one side is.

Yet when the scoring opportunity comes up for a player in fastpitch softball (or slow pitch, or modified pitch, or baseball, etc.) she’s facing a whole phalanx of opponents whose only goal is to prevent her from achieving her goal. Seems pretty unfair, doesn’t it?

And that’s why the stats of a game, even if kept honestly (versus the person who scores every contact as a hit or anything close as an error, depending on whether his/her team is at bat or in the field), don’t always tell the whole story.

For example, a hitter can slam a screaming line drive directly at the face of the opposing shortstop, who throws her glove up in instinct to protect herself. If said screaming line drive goes into the glove and the shortstop’s palmar grasp reflex (yes that’s a real thing) causes her hand to contract around the ball, the hitter is out.

Never mind that she smoked the pitch that the pitcher mistakenly threw over the heart of the plate. One of the seven fielders happened to be in the way of the ball as it was on its way to being a double and turned that great contact into a drop of a few percentage points in her batting average.

Or what about the well-hit ball to the outfield that goes to the person the other team is trying to hide? She puts her glove up over head to make sure the ball doesn’t hit her, and instead it nestles softly in the web like a bird landing in its nest.

The hitter did nothing wrong, and the fielder, quite frankly, didn’t do anything intentionally right, but the fielder gets high fives while the hitter gets nothing except another ding against her batting average. And those are just the extreme examples.

During the course of the game most times there are seven fielders behind the pitcher, plus the pitcher herself, whose job it is to make sure the hitter doesn’t reach base. And then you have the catcher whose job it is to clean up anything around the plate. That’s a pretty stacked deck.

The only way the hitter can be absolutely assured of not being out after contact is to drive the pitch over the fence. And while the number of hitters doing so has increased dramatically over the last several years, those are still a low percentage of all contacts made.

So the next time you’re wondering why failing 7 out of 10 times at the plate makes someone an all-star, remember that the odds are stacked against the hitter from the beginning. And beating 9 on 1 odds is a pretty good reason to celebrate no matter how it happens.